SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

With the way political ads are bombarding our TV sets, the 2016 polls may well turn out to be the most expensive in our history. And the official campaign period hasn’t even started yet.

With the way political ads are bombarding our TV sets, the 2016 polls may well turn out to be the most expensive in our history. And the official campaign period hasn’t even started yet.

Reports indicate that from January to November 2015, candidates for national and local electoral posts have already spent at least P3.55 billion on TV ads, or P323 million per month for 11 months.

The figures are disputed, however, as to who has spent the most, and Nielsen plans to set the record straight in a definitive report to be released late January.

Compared to the government’s budget of P2.6 trillion in 2015, or the P2.4 billion we lose daily to Metro Manila’s “carmaggedon,” these amounts may seem minuscule. But if you think about the range of social services and good causes these sums could have been allocated to instead, they all seem exorbitant (even “scandalous” as some put it).

For instance, such amounts could have easily covered the Department of Health’s 2016 budget for dengue vaccines (P3 billion), or its budget for contraceptive supplies and HIV-AIDS programs (P1 billion) that was removed during the deliberations of the Senate and House bicameral conference committee.

We’ve only just begun in this election’s campaign spending spree, which seems to revolve around the principal belief that more money translates into more votes. But is it always the case?

Does election spending translate into votes?

Offhand, it would seem that more money is related to more electoral success. Some studies show, however, that it is not so much the campaign money that brings success, but the candidates’ inherent traits or popularity which bring in money from the supporters.

One rigorous study on US congressional contests found that, when one controls for the effect of candidates’ abilities, doubling campaign spending resulted only in an extra 1% of the votes – a negligible impact.

Even here in the Philippines we see some evidence of money failing to ensure electoral success. For instance, despite having supposedly spent billions before and during the 2010 campaign season, former senator and presidential aspirant Manny Villar lost to President Aquino by a huge margin.

If money does not really guarantee votes, why do politicians continue to splurge anyway? Perhaps, some candidates have no choice: by not spending enough, less popular candidates forgo a sporting chance of being elected.

Luckily for some, a lack of popularity doesn’t necessitate a colossal campaign bill. Lesser-known candidates can take advantage of inexpensive techniques to garner more votes, including some well-known psychological and behavioral hacks.

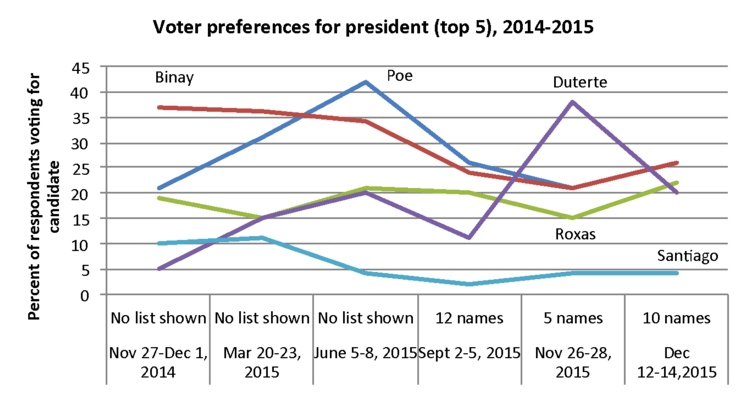

The results of the Social Weather Stations (SWS) surveys in 2015, for example, exemplify the importance of so-called “framing effects,” or the way survey questions themselves influence people’s responses.

When Davao City Mayor Duterte’s name figured prominently in the November 26-28 survey question, and the list of candidates went down from 12 names to 5, Duterte’s approval rating jumped almost fourfold. This advantage disappeared in the next survey round when the number of names was increased from 5 to 10. (READ: Magic in Duterte survey? The case of vanishing survey tables)

Note that this boost in popularity came despite Duterte having spent just a fifth of what Vice President Binay spent on TV ads in the same period last year. (READ: Duterte: Not spending my own money for TV ads)

Does election spending boost the economy?

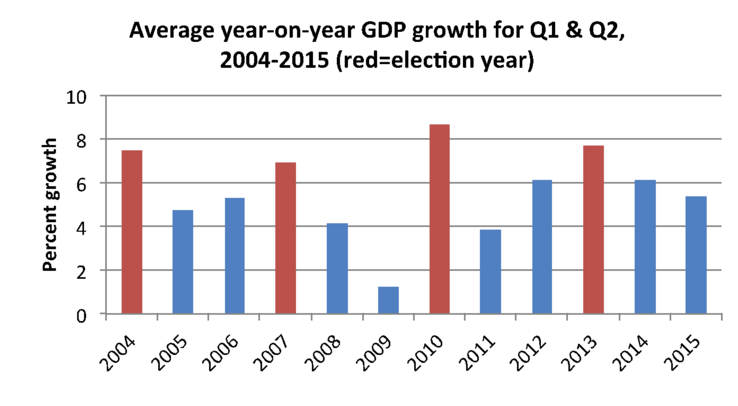

If election money does not necessarily bring votes, and is hardly a definitive determinant of electoral success, does it at least boost the economy?

Back-of-the-envelope calculations using official GDP figures show that indeed there seems to be an uptick of national output growth correlated with election years. Specifically, there has been a 3 percentage-point difference between average growth rates in the first half of election versus non-election years since 2004.

A more thorough study showed that the 2007 midterm elections resulted in as much as P13.5 billion extra spending in the economy that year, mostly on the service sector (e.g., advertising and staffing).

Thus, elections do have a real impact on the Philippine economy. But far from being broad-based and long-term, election-induced growth tends to be narrow-based and short-term.

There are also election-related transfers which, in addition to being undetected in official GDP figures, also fuel a system of rent seeking and corruption especially at the local level.

With a party system that is ideologically bankrupt and political alliances that are extremely fluid, politicians are compelled to seek help from wealthy private individuals or groups likely to expect a “return” on their political investments. An uncompetitive salary grade system further incentivizes some public officials to engage in the trading of political favors during elections.

Quid pro quo arrangements between election winners and their campaign financiers may range from ill-conceived environmental permits to monopoly privileges given to favored businessmen.

The deadweight losses arising from such perverse exchanges could easily amount to billions annually, and these could easily undo the economic stimulus effect of elections we mentioned earlier.

Things money can’t buy

No matter how much we detest the extravagance of election spending, money will always be part and parcel of any election. Perhaps the more important questions would be: How much money should be involved? From whose pockets should the money come from? And how do we regulate the flow of money?

To be sure, a number of campaign finance reform measures have already been instituted in the past, but the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) needs to clamp down harder on campaign overspending, now more than ever.

For the long term, an overhaul of our political party system seems necessary to curb the power of personality and the influence of moneyed private interests. Without such sweeping reforms, our electoral system will remain as vulnerable to rent-seeking, corruption, and clientelism as ever.

On a more practical note, how could we – as citizens and voters – reduce the influence of money in the coming elections? How do we show in our own simple way that money cannot buy our elections?

For starters, there’s no good substitute to outwitting crafty politicians at their own game than by doing the usual homework: going beyond their sound bites, carefully studying their platforms, evaluating their past performance, and engaging in debates. All of this is made easier now by the Internet and social media, which have proven increasingly impactful in the last few elections.

Moreover, voters could support deserving but cash-strapped candidates by actively volunteering in their campaign activities online or elsewhere. There are also innovative movements today like “political crowdfunding,” which is becoming increasingly popular in other countries and could help wean candidates from their reliance on big individual donors.

In the long run, let’s vote for candidates who fully support the enactment of contentious but crucial political reforms, namely the Political Party Reform Bill and the Anti-Dynasty Bill, both languishing in Congress.

We’ve always taken pride in the fact that the Philippines is the oldest democracy in Asia. But the way money and personality have figured in our past elections shows that we’ve yet to become a mature one. Proactive and critical engagement in the upcoming elections, especially among the Filipino youth, will bring us closer to the democracy we truly deserve. – Rappler.com

JC Punongbayan (@jcpunongbayan) is a PhD student at the UP School of Economics. Kevin Mandrilla (@kevinalec) is an MA student at the UP Asian Center and concurrently works as a business analyst.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.