SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

In the Philippines, political families or “dynasties” pose a sticky problem.

In the Philippines, political families or “dynasties” pose a sticky problem.

On one hand, every citizen has the right, perhaps even the duty, to serve his country by offering him or herself as a candidate for elected office. To prohibit a person from serving just because other family members are also in government, or because another family member held the same office, seems unfair.

The political family issue has been a subject of debate in the Philippines for as long as there has been a Philippines. The Constitution specifically prohibits dynasties, with the as-yet-unfulfilled proviso “as defined by law.”

But despite the spirit of that prohibition, dozens of families have maintained a permanent presence in government for generations, and some have controlled the same positions for decades. Cities and even entire provinces are routinely referred to as the “territory” or “bailiwick” of one family or another.

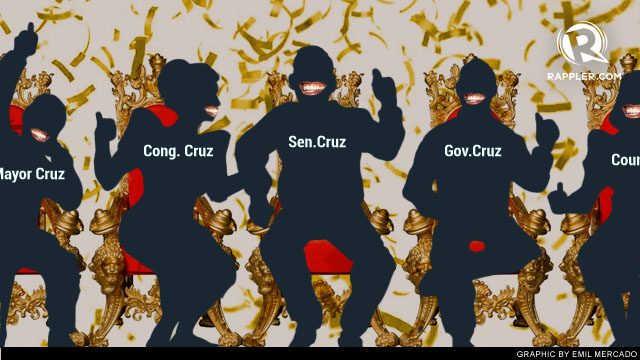

In these areas, family members often occupy multiple positions within the administration. One may be mayor, another serving on the city council, and another may even be the congressman for that particular district.

Once an incumbent has held office for the maximum period allowed by law, a relative is offered up as candidate for the position. These candidates run, and are elected, primarily on the strength of their family name, and are widely seen as place-holders for the family head, who typically reclaims the office after sitting out one or two terms.

Setting aside the effects of vote-buying and other political chicanery, Filipino voters in many areas seem to support, and prefer, these families.

Dynasty – “a family in which several members are involved in politics, particularly electoral politics. Members may be related by blood or marriage; often several generations or multiple siblings may be involved.”

— Wikipedia

By that definition, the Bush family in the United States is a dynasty. Father and son have both served as president, two sons have been governors (of different states), and a 3rd son was a congressman. The definition would also apply to the Clintons, with Bill having served as president, and wife Hillary as senator (and possibly soon to be president).

But, although the same definition applies, the Bush and Clinton “dynasties” are nothing like their Philippine counterparts. Neither family controls an office or territory the way political families do in the Philippines. In that sense, Philippine political families might be better described as “oligarchies”:

Oligarchy – “a form of power structure in which power effectively rests with a small number of people. These people could be distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, education, corporate, religious or military control. Such states are often controlled by a few prominent families who typically pass influence from one generation to the next.”

— Wikipedia

The key words here are “power” and “control,” so let’s talk about that for a moment.

In business, families often own corporations, and strive to keep control within the family. They do this primarily to protect the family’s interests, which essentially means the family’s wealth and security.

Royal families do the same, passing power from father to son (and sometimes to daughter), to protect the family and maintain its wealth. For both royal and corporate families, this is “the family business.”

Public service, on the other hand, is not a business. Legally, the only “wealth” a public servant can acquire is the satisfaction of having improved the lives of his constituents.

Other than a government salary, and a few authorized benefits like housing and transportation, a public servant is not allowed to gain financially from the job. In fact, most positions don’t even have a retirement plan. Public service is, by definition, a sacrifice.

Compare that with a career in teaching, another low-paying job that also involves service and sacrifice. Like politicians, teachers spend a lot of their own money, and the job really eats into their personal life, but most teachers dedicate their entire lives to it.

They don’t do it to get rich or to become powerful. People become teachers because they truly want to serve, and because they think they have something to offer.

But we don’t see families fighting tooth and nail to “control” teaching positions, or to pass them on to their children like they do with political positions. Why? Because in teaching there is nothing to gain beyond salary, a modest pension, and a sense of improving the lives of others.

There is no possibility of acquiring wealth or power as a teacher. When a teacher retires, she doesn’t offer a relative up to take her place.

Politics, on the other hand, operates under an entirely different paradigm. Quite a few families seem to see public office as a business, investing huge amounts of money to win a particular position, and then maintaining control of that position through a chain of family successors.

In political families, children are often groomed for entry into the family business, and participation is expected.

Some political families go to great lengths to hold their “territory,” to the extent of spending large sums of money, engaging in vote-buying and manipulation, and in some cases even maintaining armed groups as a sort of “royal guard.”

Intimidation, assault, and even assassination are not uncommon tactics. Keeping control of their territory seems to be a very high-stakes affair for some of these public servants.

This raises a very important question. What is there about an elected position that would make someone spend a fortune, engage in all sorts of dirty tactics, and sometimes even kill, to win it?

And why would any family treat it as a family business, worth fighting for, and passing from one generation to the next, when there is no possibility of gaining from it?

Unless…it really is a business.

And why does anyone go into any business? To make money. It’s that simple.

A big part of any elected official’s job is to be “in charge of the money.” A mayor, for example, uses the city budget to pay salaries, build roads, and fund social programs, among other things.

A system of legal requirements, called checks-and-balances, is supposed to ensure the money is used properly, but to be effective that system needs at least a few honest people.

In many areas of government, these checks-and-balances are apparently pretty easy to bypass. Through bribes, kickbacks, “bonuses,” and simple loyalty, the people in government who are supposed to safeguard taxpayer money simply turn a blind eye to its misuse.

This is made even easier when some of those people are related to the elected official in charge. It’s unlikely that a councilman, for example, who is also the son of the mayor, would ever vote against one of his fathers programs or actions, no matter how questionable it might be.

And it’s even more unlikely that the child would challenge the legality of that program. As a result, elected officials easily divert public money, through kickback schemes, sweetheart deals, overpriced projects, and a host of other creative ways to enrich themselves.

In these situations, “checks-and-balances” is little more than an illusion.

This, in a nutshell, is the real problem with political families. Strategically-placed family members, as in the case of a mayor whose child is on the city council, or a governor who is succeeded by his wife, can all too easily defeat the checks-and-balances which are designed to prevent a government official from enriching himself at the expense of the taxpayer.

Any effort to legally define a dynasty in the context of Philippine politics, and any laws to limit the power of political families, should focus on ensuring that related elected officials are not allowed to hold positions that would enable them to defeat checks-and-balances, or that one family member is not in a position to protect another who may be doing wrong.

Beyond that, voters have the right to choose whoever they think is best qualified. Or, to be more accurate, voters have the right to choose whoever they want to choose, whether that person is qualified or not!

A dozen members of the same family, all holding elected office simultaneously, are no threat as long as they are not serving in positions where they can defeat check-and-balance safeguards. As long as that condition is met, let them serve!

And one final note.

As I’ve already mentioned, the real reason the “political family” situation exists in the first place is because there is clearly profit in politics. Eliminate the profit factor and you eliminate the draw of elected office as a family business.

If it were not so easy for elected officials to gain financially, the only families that would want their sons or daughters to follow in their fathers’ political footsteps would be those who are honestly motivated to serve. And those are the kind of people we truly need in government.

So if we want to reduce the harmful effects of dynasties, we shouldn’t try to control the families; we should try to control the profit. The dynasty is another problem that will simply evaporate once its root causes are addressed. – Rappler.com

Michael Brown is a retired member of the US Air Force, and has lived over 16 years in the Philippines. He writes on English, traffic management, law enforcement, and more recently, government. Follow him on Twitter at @M_i_c_h_a_e_l

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.