SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

SINGAPORE – Indonesian police raided what they said was a terrorist safehouse on the outskirts of Jakarta Friday, March 30, killing two suspected terrorists. This is the third event in 3 weeks, showing continued activity and highlighting the evolution of Jemaah Islamiyah or JI, Al-Qaeda’s arm in Southeast Asia.

JI is the terrorist network that carried out the deadliest attacks in Indonesia, including the 2002 Bali bombings which killed 202 people.

On Thursday, March 29, Indonesia’s top counter-terrorism official, Ansyaad Mbai, linked a package bomb in Paris delivered to the Indonesian embassy on March 21 to this same terrorist network. Mbai identified French national Frederic C Jean Salvi as a suspect. Salvi has been on Indonesia’s wanted list since 2010, discovered during investigations into JI.

“There were strong indications he was involved in the bombing at our mission in Paris,” said Mbai.

This comes after the March 18 shootout in Bali, which killed 5 suspected terrorists. Mbai said the men planned to bomb targets, including the “La Vida Loca” bar.

As global funding dries up, more cells – once part of JI”s network – are turning to crime. Police said the suspects were planning to rob money changers and jewelers to raise money for its attacks.

These raids are part of a pattern that can clearly be linked to the same social network behind Indonesia’s deadliest attacks. The Bali attacks in 2002 were followed a year later by the JW Marriott attack, in 2004 by the Australian embassy attack, the 2nd Bali bombing in 2005 and the 2009 Jakarta hotel attacks.

During a presentation to top security officers of Fortune 500 companies in the International Security Management Association (ISMA) and the US State Department’s Overseas Advisory Council (OSAC), I outlined 3 waves of Islamist terrorism of one social network, Darul Islam, in Indonesia. These 3 waves represent cycles of regeneration and evolution of the same social network.

Waves of terror

Predating Al-Qaeda, the first wave was from 1948 to 1992 when Darul Islam was a nationalist movement for an Islamic state.

The second wave was from 1993 to 2005, when nationalist sentiments were co-opted – and subsumed – by the global jihad. Al-Qaeda coopted Jemaah Islamiyah, built on the Darul Islam network. In turn, JI acted as an umbrella organization which coopted domestic groups in Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries.

The third wave began in 2005 and runs until today, when the JI ideology is dispersed through a social movement, much like Al-Qaeda.

Terror networks are far from static.

They evolve over time, particularly if they’re under siege by law enforcement. In many ways, Al-Qaeda and Jemaah Islamiyah’s networks evolved the same way after 9/11 and Bali.

Their centralized command structures collapsed, and their operational capabilities were degraded after enough hubs in the networks were killed or captured. Essentially, their top and middle rank leadership were gouged out, damaging each network’s ability to carry out sophisticated large-scale operations.

Still, isolated nodes and cells from the old networks remained and continued to spread the ideology – bringing in new recruits in a more haphazard, decentralized pattern.

In 2010 and 2011, smaller, more ad-hoc, less professional cells carried out attacks without central coordination.

While each network is weaker, it’s harder for law enforcement to predict when and where the next attacks will occur.

JI’s self-regeneration

In 2010, smaller, disparate attacks happened more frequently. There remains a constant danger these isolated cells and nodes may spontaneously regenerate some form of a network around them to carry out operations.

This is exactly what happened when Dulmatin returned from the Philippines to Indonesia in 2007. A year later, JI’s emir, Abu Bakar Ba’asyir, created a new group he called Jemaah Ansharut Tauhid (JAT).

Most of JI’s members followed Ba’asyir, including the remaining Afghan-trained JI members. JAT, according to counterterrorism officials, is JI’s self-regeneration.

“JAT is the new camouflage of JI,” said Mbai, the chief of Indonesia’s National Counter-Terrorism Agency (BNPT). “It has the same leader, Abu Bakar Ba’asyir, and most of the key figures of JAT are also JI. So I call this the new jacket of JI.”

In February 2010, Indonesian authorities dismantled a training camp in Aceh created by Dulmatin and Ba’asyir. The foiled terror plot in Bali March 18, say officials, is linked to Ba’asyir and to JAT.

“We are quite surprised by the resilience of this movement,” said Tito Karnavian, the deputy chief of Indonesia’s National Counter-Terrorism Agency (BNPT) and former head of police anti-terror force, Densus 88. “Because amidst quite intense operations and raids by us, it still survives.”

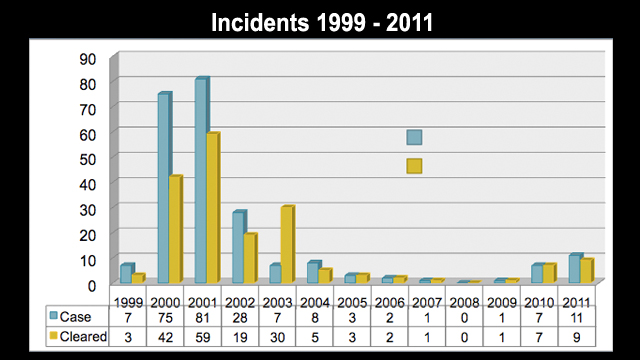

In Singapore, Tito pointed out that more men were arrested in 2010 (more than 100) than at any other time – even after the first Bali attacks. Nearly 700 people have been arrested since then with at least 575 prosecuted in court.

Tito said the new groups come from “the same community” – agreeing with the idea that all the groups were part of the old Darul Islam social network.

He said, “it remains a social network, but it’s been divided into two. He identifies the strands as the JI-JAT-Hisbah-Tawhid Wal Jihad and the NII (Negara Islam Indonesia).

Tito pointed out that many JI members arrested since the crackdown began in 2002 were released in 2007. Many of them were re-arrested working with JAT in the Aceh training camp or as part of other foiled plots.

Last month, the United States designated JAT a foreign terrorist organization.

“JAT is the most violent terrorist group in Southeast Asia,” said Rohan Gunaratna, head of the International Centre for Political Violence & Terrorism Research in Singapore. “The threat is still very significant because the terrorists continue to plan and prepare attacks.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.