SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In February 2014, the Philippine government finally recovered around $30 million from multi-million dollar accounts that the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos stashed away in Swiss banks.

What allowed the government to gain control of the money were forfeiture cases which proved that amounts contained in the accounts exceeded the total legal income of Marcos and his wife Imelda while they were in office. Evidence used to prove the government’s case included the financial disclosure statements filed by the Marcoses while in office.

It took the government almost 3 decades to recover the money. Neither Marcos, nor his wife Imelda, were ever convicted of any wrongdoing.

No laggard?

The Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, the law that required the Marcoses to file those disclosure statements dates back to the 1960s. In 1989, years after the Marcoses were booted out of office, the Philippine Congress enacted a new law which allowed the public to access and photocopy the assets and liabilities statements.

Since then, the law has been used to prove a plunder case against another president (Joseph Estrada), impeach then remove a chief justice (Renato Corona), file cases against corrupt generals and lately, support the filing of charges against sitting senators.

That the Philippines enacted such a law almost 3 decades ago is significant because as of 2006, a World Bank study showed that only 31 of 101 countries that require government officials to declare their income and/or assets mandate that such declarations or a summary should be made available to the public.

This implies that the Philippines is no laggard when it comes to laws allowing access to public information.

Constitutionally-mandated right

The people’s right to information on matters of public concern has been constitutionally recognized in the country since 1973.

Section 6. The right of the people to information on matters of public concern shall be recognized. Access to official records, and to documents and papers pertaining to official acts, transactions, or decisions, shall be afforded the citizen subject to such limitations as may be provided by law.

– Bill of Rights, 1973 Constitution

After the 1986 Edsa uprising ousted the Marcos dictatorship, this right was further expanded in the 1987 Constitution to include access to research data used as basis for policy development.

And while there is no enabling law yet on access to information, the Philippine Supreme Court has already ruled, in more than one occasion, that the constitutional mandate is enforceable.

In fact, the Code of Ethics of government officials—the same law that mandates public access to financial disclosure statements of government officials—also makes it the obligation of public officials and employees to make documents accessible to the public.

The implementing rules of this law helped institute a system of promoting transparency of transactions and access to government information. It also sets limits of access.

More recently, the Aquino administration has been making strides in promoting transparency in government by proactively disclosing budget and project documents.

It is no small wonder then that while the Senate has approved the bill on 3rd reading, members of the House of Representatives continue to drag their heels on the freedom of information law.

Because if those laws are already in place, why then is an access to information law still necessary?

To help answer that question, Rappler, with the support of the Friedrich Naumann Foundation, analyzed freedom of information laws in other parts of the world. We noted these common features in the laws we studied:

- an overall policy making information available

- limits of access

- prescribed process by which information may be accessed, cost of access, and processes for appealing request refusals

- in recent cases measures to ensure that access policies are enforced through oversight bodies and penalty clauses

Uneven, selective release of information

In the Philippines, while the Code of Ethics does make it the obligation of government offices to make public documents available, journalists have found time and again that requests may be refused without any clear grounds.

Selective release is true even for requests for asset disclosure statements despite the clause in the law that specifically requires custodians to make such documents available for duplication within 10 days after they have been received.

Three years since the impeachment trial, for example, the House that prosecuted former chief justice Corona has yet to create rules releasing the disclosure statements of its own members.

In place of SALNs, the House only releases a summary of the wealth of House members in a matrix that includes the total amount of real properties, personal properties, total assets, liabilities and net worth of each lawmaker. (READ: Solons from poorest region among richest in Congress).

Rappler’s request for the full copies of the SALNs of lawmakers, which we file every year, has been repeatedly denied.

This is in stark contrast with its co-equal branch, the Senate, which regularly releases the full copies of statements to media.

The Government Procurement Reform Act also mandates transparency in the procurement processes and equal access to information for bidders but stops short of requiring access to the actual contracts.

Oftentimes, journalists have to go through insiders to get copies of government contracts.

Short of going to court, which can be expensive and time consuming, there is no clear process for appealing refusals of requests for information.

Bias for access

Instead of confining access to certain types of information, FOI laws generally make access the default policy.

The website of the UK’s Information Commissioners’ Office expounds on this in instructions to authorities required to release information:

“Remember you (authority) are required to disclose requested information unless there is good reason not to. It is your responsibility to show why you should be allowed to refuse a request, so it is in your interests to co-operate fully with our investigation.

In rare circumstances when a public authority persistently refuses to co-operate with us, we can issue an information notice. This is a legally binding notice, requiring an authority to give us the information or reasons we have asked for.”

The UK system simplifies access such that all a person needs to do is to:

- contact the relevant authority directly;

- make the request (verbal or in writing)

- give his real name; and

- give an address (postal or email) to which the authority can reply

Instructions on the UK Information Commissioners’ website says the requester does not need to mention the FOI or even know that whether the information is covered by the FOI. He does not even have to explain why he wants the information.

This is vastly different from current practice in Philippine government offices where those requesting for information are required to justify why they should be given access.

Limits to access

Those who are lukewarm to the proposed FOI law claim that this could allow sensitive government information to fall in the hands of “bad social elements,” “enemies of the state” or even “irresponsible media.”

But FOI laws also typically set limits of access or grounds for refusal of requests. Among the countries whose laws were reviewed by Rappler, grounds for refusal usually include a list of exemptions, which include these types of information:

- security, national defense and public safety

- information relating to unfinished/ongoing legal proceedings, investigations

- trade and business/commercial interests

- international relations / diplomacy

- administrative matters such as inter or intra agency memoranda

- personal privacy

This does not mean that the public is totally barred from accessing such information. In some cases, information included in the exemptions list may still be accessed if clear public interest is invoked. This is done in the appeals process.

The FOI laws of Norway, Sweden and Japan specifically state that exemptions may be lifted if need for access outweighs reasons for exemptions.

Preserving information

Another important feature of FOI laws in countries Rappler studied are provisions requiring note-taking, recording and archiving or protecting information.

This is a policy wherein information, especially verbal ones passed on during meetings, are duly noted down and kept in a journal or register and is properly archived and protected.

In the Philippines, duty to record and “from time to time” publish congressional proceedings, including how members of Congress voted, has been constitutionally mandated since as far back as the 1935 Constitution. The only thing exempted from this mandate were proceedings on matters that may affect national security.

In practice, however, a significant part of congressional budget proceedings, including records on amendments to the national budget, never make it to publicly available records.

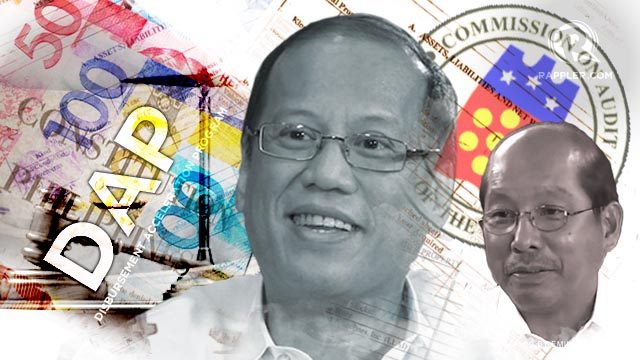

And while the Aquino administration has indeed undertaken efforts to make budget information more transparent, information that finally came out following the controversy over the Priority Development Assistance Fund and the Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP) clearly show that much about government financial transactions are still hidden from the public eye.

More on Rappler’s coverage of the pork barrel and other discretionary funds here.

Consider this: letters and emails from politicians requesting for release of funds and responses to such requests would have been part of accessible information if the Philippines had an FOI law similar to that of Sweden.

Oversight, penalties

One thing that is also clearly missing in the Philippines is a body designated to oversee that access to information is indeed enforced. There are also no penalties for officials who whimsically refuse requests for access.

Among the 15 countries in the Rappler study, only Denmark, Norway, Netherlands and Finland have no independent oversight bodies. The UK, USA, Sweden, Australia, Canada, Ecuador, Germany, Thailand, Indonesia, Japan all have oversight bodies.

Most oversight bodies are mandated to:

- actively oversee the compliance of the law

- act as mediator / settle disputes

- receive & examine appeals, complaints

- in some cases, perform investigations

Oversight bodies need not be new government entities. In the case of Ecuador, Sweden and New Zealand, existing bodies such as the Ombudsman, the Public Defender & the Chancellor of Justice were tasked to investigate FOI-related complaints.

Because they already have prosecutorial powers, the functions given to these bodies include prosecuting offenses.

Penal sanctions are also typical of newer FOI laws, Rappler’s study shows.

The United Kingdom, which enacted its first FOI in 2000, penalizes individuals who deliberately destroy, alter, block access, conceal public info with the intention of preventing disclosure of that info with a maximum fine of 5,000 British pounds (over US$8,500).

Much closer to home, the Indonesian FOI punishes officials that deliberately disregard to provide or publish public information promptly and in the process causes harm to other persons with imprisonment of up to 1 (one) year a fine of not more than 5,000,000.00 rupiahs (or US$428).

Think of the impact such a policy would have on information that could affect public safety and welfare.

Proactive publication, open data, citizen audit

Perhaps the biggest argument for enacting an FOI in the Philippines is the need to institutionalize access to government data and information online in open, machine-readable formats.

Making information immediately accessible online is crucial to transparency as it eliminates backlog in processing requests for access. India’s quandary, having to manage over 2 million requests for information, highlights this need.

In addition, given available crowdsourcing technologies, access to open data—particularly data on government financial transactions—could prevent corruption as it could empower people to monitor resources supposedly released to their communities.

![]()

This helps hasten and widen the scope of the audit and address accusations of political bias in the auditing of public funds. Remember, the report that the Commission on Audit released in 2013 covered transactions from 2007 to 2009–almost half a decade too late.

As Budget Undersecretary Richard Moya said, opening up the data would “make auditing everybody’s business.”

While the Aquino administration has indeed taken steps to making machine-readable information available to the public through the Open Data Portal, Rappler’s own review of the contents of the portal shows that available data still falls far short of what is known to be kept by most government offices. In many cases, only summaries are provided—not granular, verifiable data. Data is also not updated in a timely fashion.

Clearly, a little push is still necessary to get data guardians in government to share their data. Such a provision in the law would also help ensure that the initiative will outlast the current administration.

Remember the claim of the Philippine National Police that what may seem like a surge in crime only means crime figures are reported more truthfully now?

It would be interesting to have access to crime data and see how much of what is logged in police blotters for every station every day actually make it to national crime statistics.

Balancing act

As Congress continues to dilly-dally on the Philippines’ first FOI, it is worth noting that in most of the countries with right to information laws, these laws have not remained static since they were first approved.

Changes or amendments were made as part of a balancing act between access, privacy and national security/ protection of “state secrets.”

Sweden, the first country to enact a law on Freedom of Information (1776), passed a Secrecy Ordinance in 1980. In 2009, it balanced access and secrecy through The Public Access to Information and Secrecy Act.

The United States, the first country outside Europe to adopt such a law in 1966, has replaced, revoked, vetoed, and reinstated provisions of the law so many times as the US government responded to issues and scandals that rocked the White House.

In 2007, years after the 9/11 tragedy traumatized the country, the US Congress passed The Open Government Act of 2007. Clearly, it is possible to balance concerns over security with the need for transparency.

At the end of the day, it’s really a question of whether we want to wait for another 3 decades to recover money lost through corruption, as in the case of the Marcos wealth, or we want to prevent or reduce corruption and abuse of office by making processes more transparent now. – with research by Nigel Tan, Leilani Chavez and Wayne Manuel / Rappler.com

The research used in this article was supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom. The research used in this article was supported by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom. |

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.