SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[#RapplerReads]: The power of telling children’s stories in local languages](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/08/Rappler-Reads-01.jpg)

Editor’s note: #RapplerReads is a project of the BrandRap team. We earn a commission every time you shop through the affiliate links below.

It’s not surprising to know that the Philippines, a country that consists of around 7,640 islands, has more than 100 languages. Most of these languages are considered indigenous, while some are already “dying” and “in trouble.”

While the common languages we use daily are Filipino, English, and Tagalog, it does not mean we should care less about the country’s native languages, such as Waray, Ilokano, and Hiligaynon. After all, when a language dies, a fragment of our identity, history, and culture disappears. How do we save and protect our languages then?

For Aklat Alamid, an independent publishing house in the Philippines, it’s necessary to tell stories in local languages – an idea born out of the founders’ love for children’s literature.

“Nagkita kami ni China sa Indonesia in 2016 sa isang children’s literary conference sa Jakarta, Indonesia. Nag usap-usap kami tapos naisip namin na wala pang publishing house na dedicated to children’s books written in different languages of the Philippines. Puro English and Filipino,” said Aklat Alamid co-founder MJ Cagumbay Tumamac, who is also its administrative head.

Aklat Alamid co-founder and senior editor China Patria M. De Vera shared that the shame and guilt for not learning Bisaya and Pangasinense when she was younger also spurred this advocacy.

“Yung parents ko ay from the region – Pangasinan and Mindanao. . . Kami na yung generation na hindi na natutunan ‘yung wika. Nalulungkot ako kasi mahalaga yun. I think it’s my way of giving back, paghingi ng paumanhin sa hindi pagkatuto ng Pangasinense at Bisaya,” she said.

(My parents are from Pangasinan and Mindanao. . . I belong to the generation that wasn’t able to learn our native language anymore. It’s sad because I know it’s important. I think this is my way of giving back and asking forgiveness for not learning Pangasinense and Bisaya.)

When you look up the meaning of alamid, you will find that it refers to a civet or a wild mountain cat which is a rare and endemic species in the Philippines.

Like the Philippine Palm Civet, there are languages in our country that are in danger of becoming extinct. And so when the Aklat Alamid founders were thinking of a name and logo for their publishing company, alamid came to mind.

“Naisip namin na gusto namin i-push na pangalagaan din yung mga endangered languages natin at mas hindi commercial ‘yung approach sa paglilimbag,” MJ continued.

(We wanted to help preserve our endangered languages and follow a non-commercial approach to printing books.)

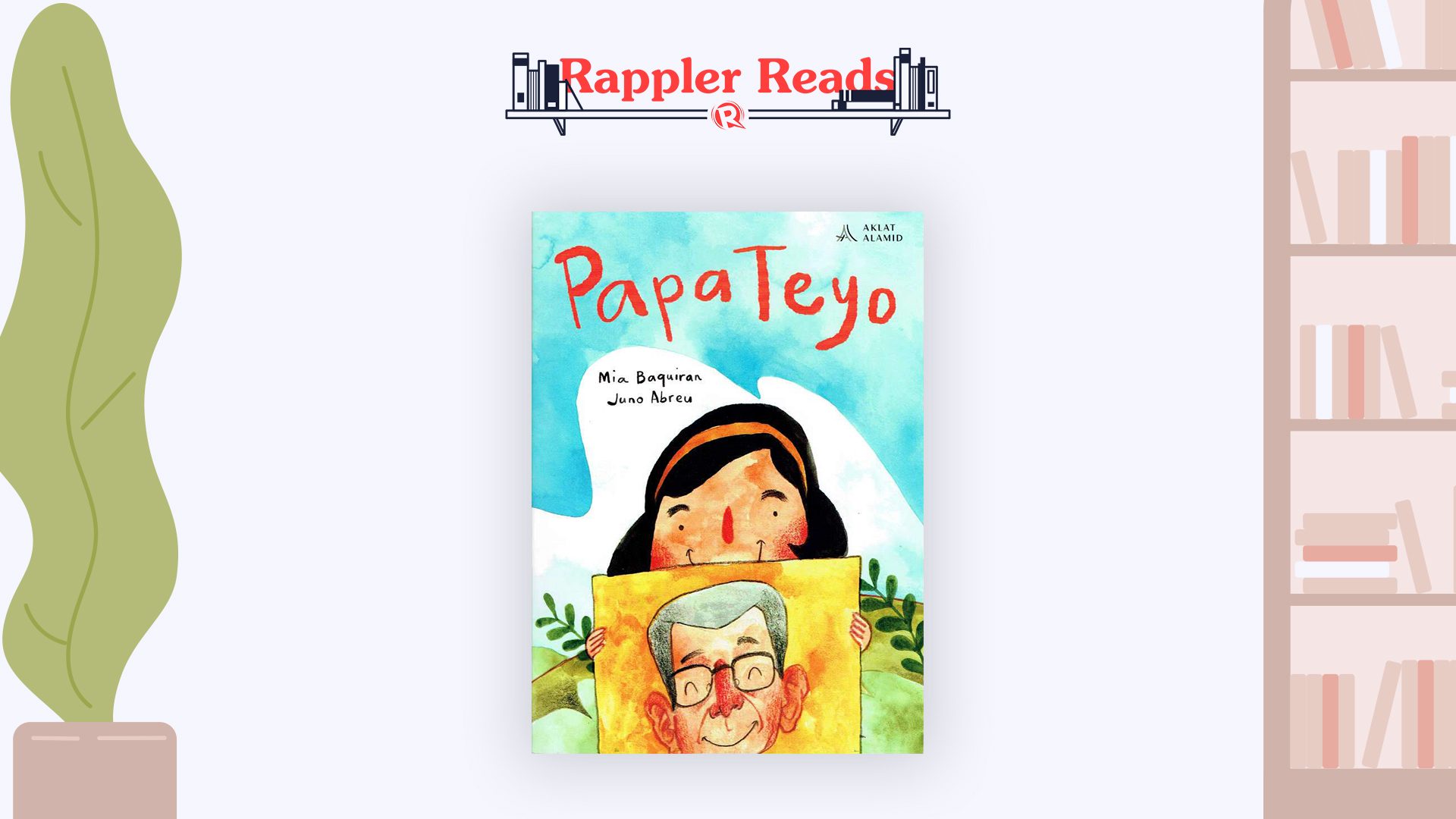

Since 2017, Aklat Alamid has been producing children’s books in different Philippine languages. Papa Teyo is Mia Baquiran’s story about a girl and her grandfather, written in English and Ibanag, the native language spoken in Northern Luzon, particularly in Cagayan and Isabela provinces.

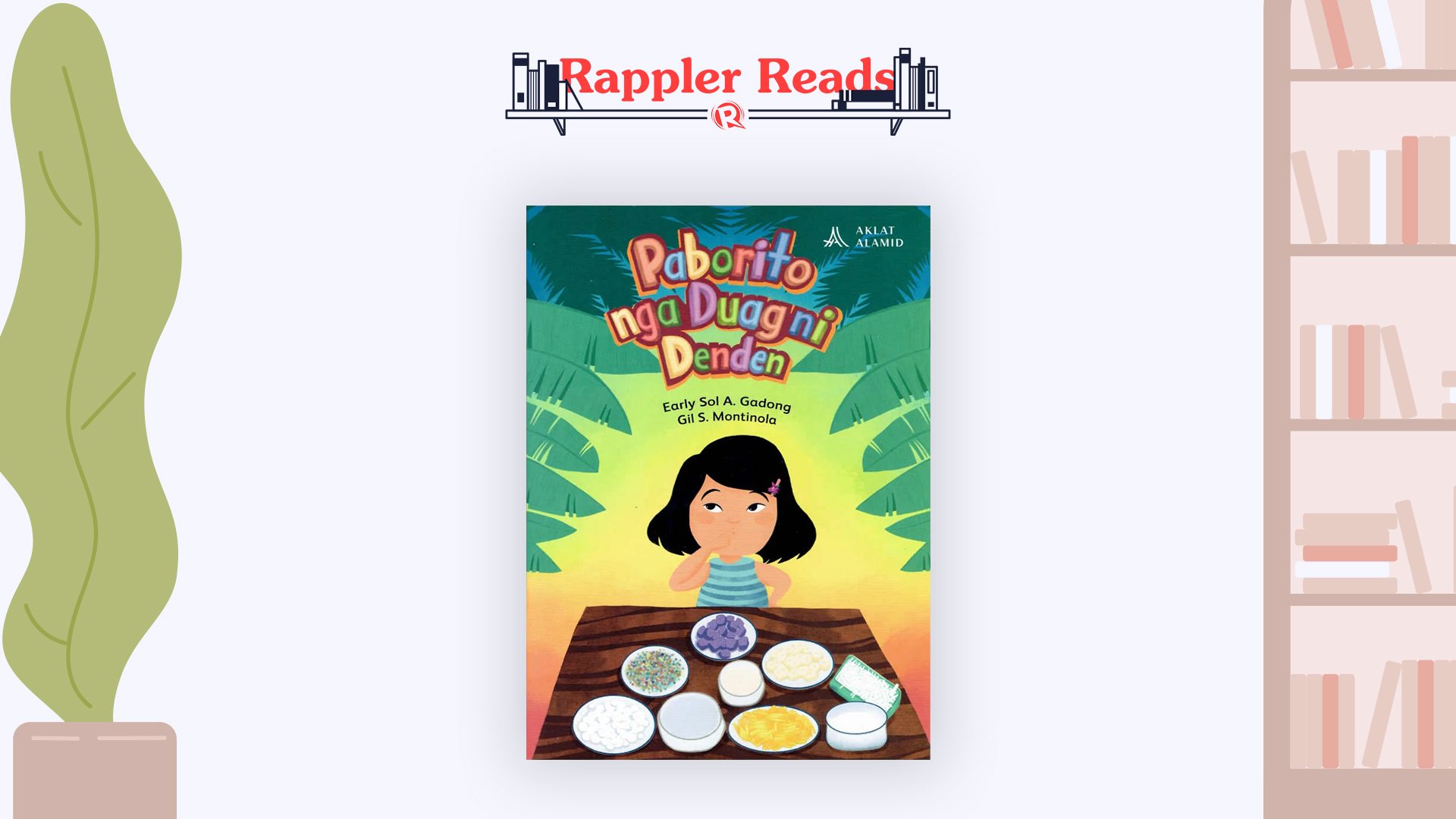

There’s also Paborito nga Duag ni Denden, a savory story about a young girl’s favorite merienda, written by Early Sol A. Gadong and illustrated by Gil S. Montinola. It is told in Hiligaynon and translated in Filipino.

At a first glance, you would notice the colorful and whimsical covers of Aklat Alamid children’s books.

When making the illustrations, marketing head John Romeo Venturero said that they want to involve the illustrators in the book production process. As much as possible, the illustrators they choose are those who live in the region where the children’s story originated to fully represent its language and culture.

“In short, we’re trying to open the gates. We’re trying not to gate keep [the] book production. We want to open the doors for the creators from all the regions [in the Philippines], China said.

In 2020, however, Aklat Alamid’s book production was halted due to the pandemic. A year later, they resumed their operations.

“Hanggang ngayon, inaaral pa rin namin yun paano kami magfu-function kasi syempre at the end of the day, you really have to earn para umikot [yung pera]. Para magkaroon ka ng pang-print pang-distribute, pang-bigay ng honorarium . . .” said China.

(Until now, we’re still learning how to function since, at the end of the day, we still really need to earn and grow money – so we can have the funds to distribute books and pay for the honorarium.)

Today, Aklat Alamid continues to collaborate with individuals, organizations, agencies, and other groups to conduct activities that help nurture their advocacy of creating books in regional languages.

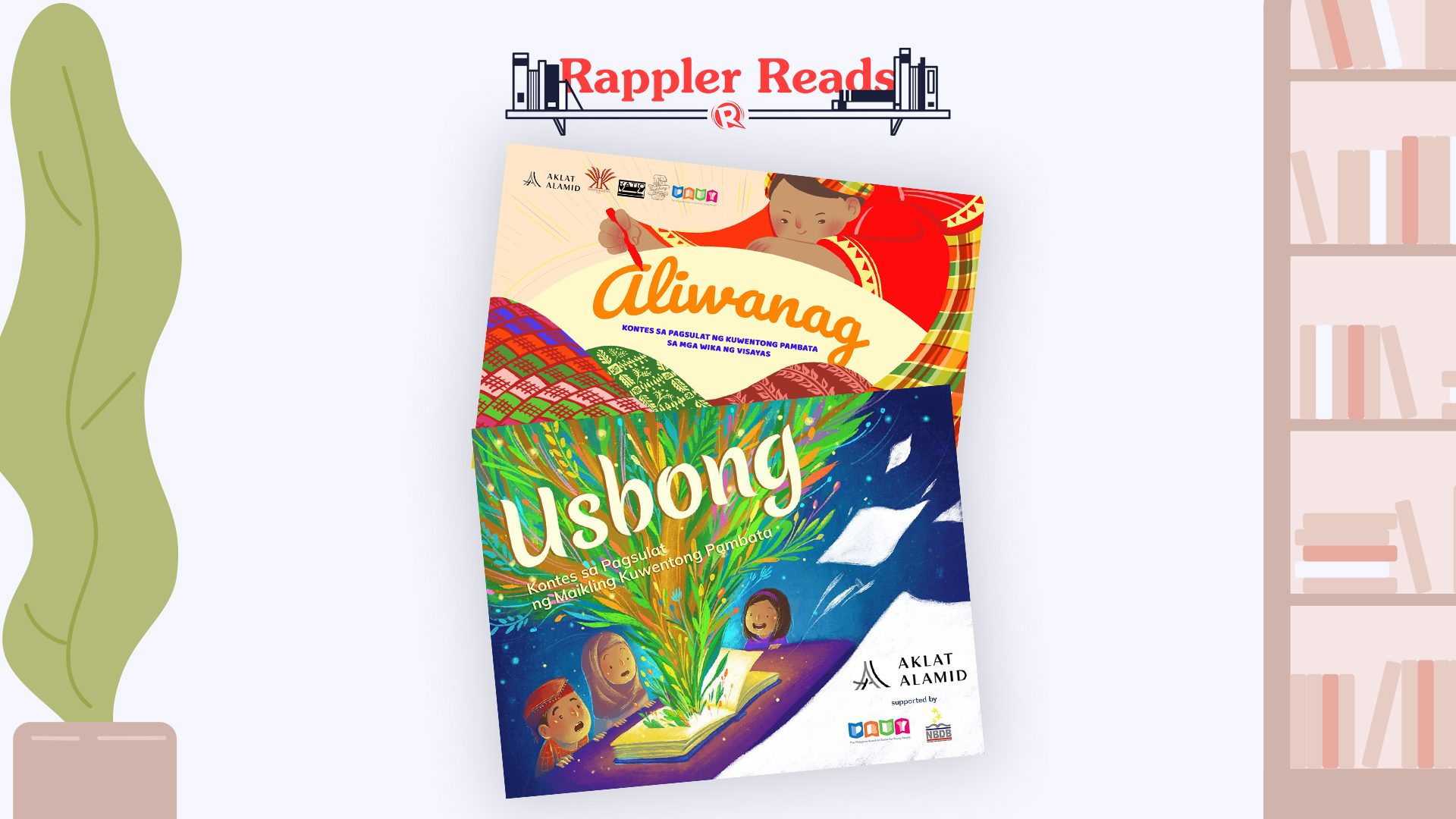

Their stories come from submissions and workshops and contests such as Aliwanag and Usbong – Aklat Alamid’s children’s story writing contests for writers from Visayas and Mindanao respectively.

“Importante kasi talaga na mayroong representation yung bata sa iba’t-ibang rehiyon. Karaniwan kasi lalo na sa mainstream publishing, nakasentro sa karanasan sa isang klase ng bata lang – yung bata sa lungsod, batang Kristiyano, batang middle-class,” John Romeo said.

(Representation of children from different regions is really important. It’s common, particularly in mainstream publishing, to focus on the experiences of specific children – a child from the city, a Catholic child, or a middle-class child.)

He said that children seeing themselves in stories is crucial as they grow up and form their own identities.

“Pag pupunta ka sa mga regions, makikita mo na mayroon palang batang magsasaka, mga batang mangingisda, o mga bata na kabilang sa isang indigenous community. . . Importante na marepresent sila sa panitikan. . .”

(When you go to different regions, you will see that there are children who work as farmers and fishermen, or children who belong to an indigeneous community. . . It’s important to represent these children in literature.)

Among the upcoming Aklat Alamid titles we can look forward to this year are the following: Gusto Maglupad ni Bangsi (Gustong Lumipad ni Bangsi), Ka Um Umagen Shin Nanligvatan Se Lijang Uta (The Legend of Uta Cave), Ang Akon Amiga nga Nagpuyo sa Kulo (My Friend who Lives in the Breadfruit Tree), and Ang Buhok nga Naglimpyo kang Suba (Ang Buhok na Naglinis ng Ilog).

These children’s books are written in various local languages such as Filipino, Binisaya, Kalinga, Bantayanon, and Kinaray-a – recommended for young readers who want to learn more about the unique culture and languages of the Philippines.

As we celebrate Buwan ng Wika, one of the ways to show our love and appreciation for our languages is by spreading the word about Aklat Alamid and reading their books starting with Papa Teyo and Paborito nga Duag ni Denden. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.