SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

.jpg)

MANILA, Philippines – Join the #WhyMining online discussion on Friday, October 26, for a Twitter conversation on issues that involve peace and order in mining operations’ host communities.

From 4 pm to 6 pm and using the hashtag #WhyMining, representatives of business, industry, environmental, non-government groups, students and others who have a stake in or opinion on the mining industry will discuss why and how violence is prominent in mining areas.

The conversation is a take-off from the October 18 shooting incident in South Cotabato, host of Tampakan mine, that killed a pregnant indigenous tribe member. A month before, the 11-year-old son of a tribal leader opposing the large- and small-scale mining operations in Zamboanga del Sur, was gunned down on his way to school.

These are the latest in a long list of violent incidents in mining areas. Usually, these involve the killing or harming of individuals that either oppose or protect the extractive operations.

Mining operations are usually located in far-flung areas where poverty abound. The economic activities mining triggers attract different groups that want a piece of it. The military is usually caught in between or is alleged to be supporting one of the warring groups.

Extraction also happens mostly on land that is not only mineral-rich but also a key biodiversity site or home to indigenous peoples, attracting anti-mining sentiments among environmental or tribal groups.

Indigenous peoples

The Philippines has one of the most advanced laws dealing with indigenous peoples, which cedes them title to their ancestral land and then confirms their right to give their Free, Prior, Informed Consent (FPIC) to development projects on that land.

The recent incidents in South Cotabato and Zamboanga del Sur, both in Mindanao, involved indigenous peoples.

In Zamboanga del Sur, the tribe’s supporters said the bullet that killed the young victim was meant for Timuay Locencio Manda, the anti-mining chieftain of the Subanen tribe.

The military has denied that the killing was related to mining, highlighting how the industry can be part of a complex and interlocking issues, interests and players in a local area.

Supporters of tribal groups’ rights have blasted mining firms for the violence, pointing their fingers to either the security personnel, most of them heavily armed, that the miners have employed to reportedly harass and shut those who oppose the company.

The victims in South Cotabato — the pregnant Juvy Capion and her two sons — involved members of the B’laan tribe, one of the dominant ancestral tribes in the area strongly opposing the upcoming mining operations in the copper and gold-rich region. The Xstrata-Sagittarius Mines is awaiting the government’s nod to start its US$6 billion operations–the largest mining investment in the Philippines.

The Church joined the anti-mining position and cited the incident to show how mining negatively impacts social justice and human dignity.

Kalikasan Partylist was adamant, however, that the crime was due to the tribal group’s anti-mining position. In their October 20 press statement, Kalikasan “calls for the permanent and final cancellation of the Tampakan project that has indirectly claimed so many lives over the years and has been the source of increasing social strife and bloodshed even way before it starts operating.”

Rebel groups

In the case of the South Cotabato killings, among those eyed as involved is the rebel group National People’s Army (NPA), which reportedly were behind a series of ambush attacks against the mining firm’s personnel in 2008.

The victim’s husband is a fugitive tribal leader linked to NPA, which was said to be behind these attacks that killed 3 drill contractors and 2 security personnel, and also destroyed about P12 million-worth of property.

Previously, the B’laan tribesmen captured the mining firms’ Canadian geologists and their Filipino companions for hours on end to oppose mining.

Mancayan violence

Another mining-related violence also occurred in Mankayan mine of Lepanto Consolidated located Benguet province in northern Luzon.

No one has died from the months-long barricade, mostly by Mankayan residents who are Ibaloi tribe members and land claimants, but several have been wounded in a recent violent dispersal in September.

The residents have been picketing for months to stop the authorities from enforcing a a writ of preliminary injunction against the barricade, allowing the mining firm from proceeding with exploratory drilling in its gold mine site there.

Those who suffered from head lacerations and bruises included a resident and a member of the The Philippine National Police (PNP), which had over 100 policemen armed with shields and guns while escorting provincial sheriffs who would serve the court order.

Violence erupted when mine employees and company guards and the police tried to force their way through the human barricade of the residents.

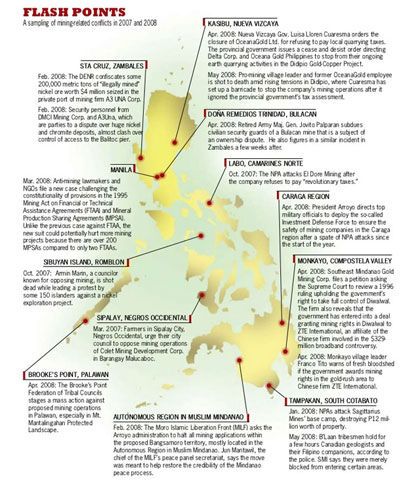

Other areas in the Philippines that are considered as flash points of mining-related conflicts include Brooke’s Point in Palawan, Sta. Cruz in Zambales and Kasibu in Nueva Vizcaya, among others.

What is your position on this issue? Join us on October 26. – Rappler.com

More on #WhyMining:

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.