SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

AT A GLANCE:

- Property data show that a good chunk of online casinos have closed shop, but immigration and employment figures indicate that Chinese workers stayed despite headwinds.

- An exit of POGOs spells trouble for the already pandemic-battered restaurant and banking industries.

- State regulators have fought for POGOs to stay, but have yet to prove their ability to regulate online casinos.

Filipinos, in general, have never welcomed online gambling. But the exodus of Philippine offshore gaming operators (POGOs) due to the coronavirus pandemic and higher taxes may not spell all good news for Manila residents.

Since POGOs were allowed to expand in Manila in 2016, businesses like properties, fintech, transportation, and restaurants have been given a massive dose of steroids by gambling money.

But while some saw the jackpot, residents realized that cultural differences were going to be an issue, more so when kidnapping, prostitution, and human trafficking were being linked to POGOs. (READ: A Chinese online gambling worker’s plight in Manila)

At a glance, the POGO exodus could trigger a sign of relief. But their departure means that ecosystems which grew around the gambling hubs are set to dry out.

Industry estimates show that POGOs bring in a whopping P551 billion in revenues to the economy yearly. So far, experts have been unable to calculate the impact of their departure.

At the same time, employment and immigration data paint a somewhat confusing scenario: Chinese workers are still here, and over a hundred online casinos are still operating, seemingly waiting out the pandemic.

Moreover, industry sources fear that unregistered POGOs have found new ways to skirt recently imposed laws and taxes by calling themselves outsourcing companies, making it even harder for the government to regulate the industry.

Office, condo vacancies

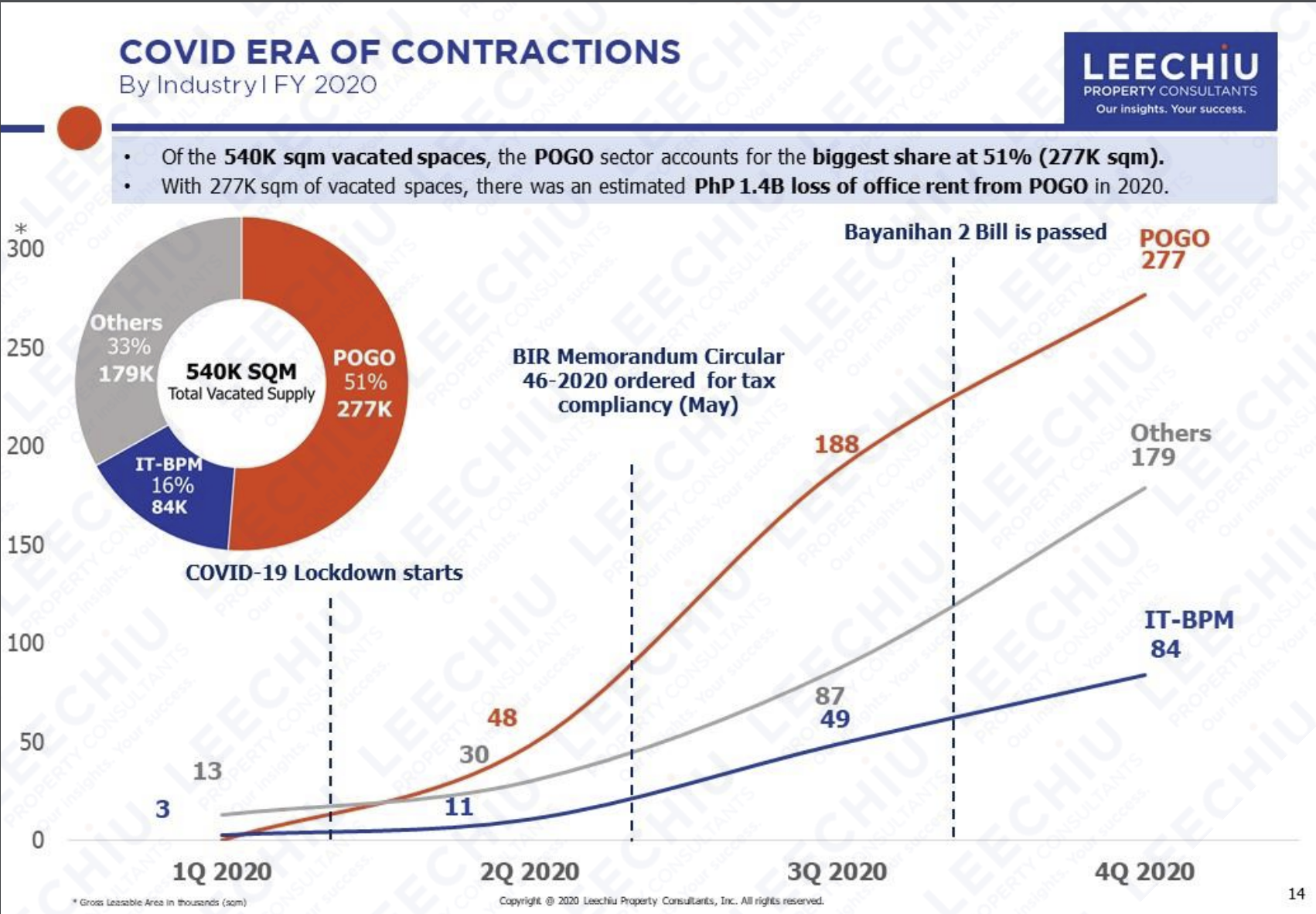

Data from Leechiu Property Consultants showed that POGOs vacated some 277,000 square meters (sqm) of office space in 2020, translating to around P1.4 billion in losses in office rent and around 127,000 job losses.

David Leechiu, chief executive officer of the property consultancy firm, said that the coronavirus lockdowns around the 2nd quarter shaved off only 48,000 sqm of POGO space.

But it rose to around 188,000 sqm in May when the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) issued a memorandum ordering tax compliance.

Vacancy soared to 277,000 sqm when the Bayanihan to Recover as One Act (Bayanihan 2) was passed. The law contained a provision that excises a 5% franchise tax from the total bets from POGOs or revenues, instead of the net income.

Bayanihan 2 wanted to raise tax collections from POGOs from about P7 billion to around P17.5 billion, as the Philippine government struggled to boost revenues amid rising costs due to the pandemic.

Despite the hefty taxes, around 125 of the 338 POGOs and service providers were presumed to have resumed operations after securing documents from the BIR and the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corporation (Pagcor).

“POGOs love the Philippines. While many have left, they will still try to be here despite the taxes, as it is much harder for them to start somewhere else,” Leechiu said.

While Leechiu believes that POGOs have done “more good” for the economy, he also cautioned property developers about the risks of betting and building their business around a single industry.

“We have advised some to not build buildings that are very high, reduce the number of floors…but some still went ahead,” Leechiu said.

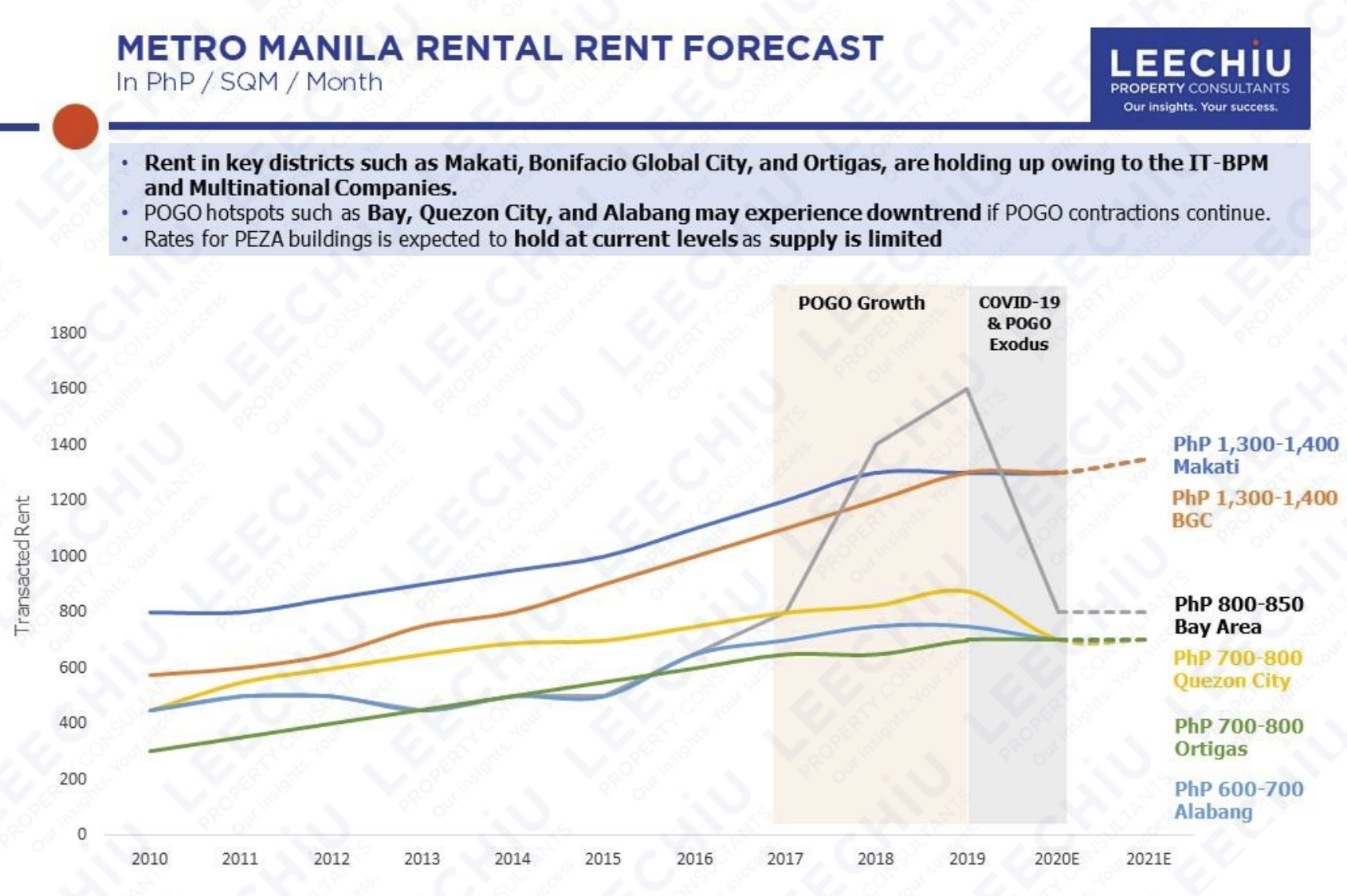

As office space vacancies rose, rent in condominiums and apartments fell, particularly in the Bay Area in Parañaque City, where most POGOs used to operate.

So what if the rich property tycoons earn less? Does it mean cheaper office space and housing for regular people? The situation is not as simple.

A banking executive who declined to be identified noted that a default or debt restructuring by property developers may shake the already pandemic-battered banking sector. (READ: From malls to banks: The pandemic’s domino effect)

“The 2008 global financial crisis had lots of reasons, but there was a property bubble which left banks exposed, then it’s a domino [effect] from there. But we don’t see that right now, we are far from that, but you’d understand why there’s some concern,” he said.

Meanwhile, Leechiu also noted that restaurants, especially those that depend on POGO workers, may find it more difficult to recover during the pandemic.

“There are restaurants that are just staying open until this December and maybe in the New Year, because this is the time people will still go out despite the pandemic. But after that, they will close,” he said.

How many left?

Property data is quite clear that around a third of POGOs have shut down.

But employment and immigration figures point to some possible early signs of recovery.

During the 3rd quarter, the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) said it released 14,959 alien employment permits (AEPs), most of which were for POGO workers.

This is much higher than the 5,311 AEPs issued in the 2nd quarter when the hard lockdowns were enforced, suggesting that some workers have either replaced some who have left, or added to an already existing workforce.

From January to September, 83,204 AEPs were issued by DOLE, 84% of which were given to POGO employees.

Of the total, Chinese workers make up most of the applications at 62,545.

But DOLE projected an influx of as much as 203,000 POGO employees this year.

“As the economic and health impacts of the pandemic continue to manifest, AEP applications have yet to regain momentum, bringing into question current projections,” DOLE said.

The recent job postings are another indicator that POGOs have only downsized operations and have not totally left.

Jobstreet, for instance, has postings looking for “beautiful, slim” female casino dealers and front-end programmers who are familiar with Mandarin.

Regulation

From releasing a primer on various news outlets which supposedly set the record straight about the industry, highlighting POGO donations amid the pandemic, and even suggesting that POGOs are business process outsourcing firms, Pagcor has clearly defended online casinos. (READ: Industry speaks up: POGOs are not BPOs)

But Pagcor, DOLE, and the BIR have yet to prove that they have ironed out compliance issues.

The BIR even admitted that POGOs have not paid P50 billion in taxes in 2019 alone.

Did they pay up this time? It is, after all, a requirement to reopen. Rappler and other news outlets have repeatedly sought comment from Pagcor and the BIR, but they have not responded to requests.

Last May, the Inquirer asked Internal Revenue Commissioner Caesar Dulay how many have not paid up, and he replied, “Marami, halos lahat (Many, almost all of them).”

At this point, can we assume that the 125 POGOs and service providers have fully paid their tax dues?

Also, note that regulators have not agreed on how many POGO workers there really are – 4 years after President Rodrigo Duterte’s policies encouraged the growth of the industry.

In May, the BIR told senators there are around 103,000 foreign workers in the POGO industry, yet the DOLE counted only over 86,000. Pagcor said there are over 93,000 workers. The numbers clearly didn’t match.

But property consultancy firms like Leechiu said the number of POGO workers went up to as high as 470,000 before the pandemic, based on the total office take-up.

With even the most basic data being debated on, industry experts worry that regulators simply can’t regulate POGOs. This has resulted in an uneven playing field.

With the pandemic’s new normal, heftier taxes, and uncertainty over whether the next Philippine president would continue to support them, POGOs face headwinds that could blow them out of the Philippines.

But with the demand for gambling in China rising despite the clampdown of the Chinese Communist Party, and with few options where to go, industry experts warn that illegal POGOs may just be hiding in plain sight, with Filipinos unable to get the most out of them. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] A new advocacy in race to financial literacy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/advocacy-race-financial-literacy-April-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[In This Economy] Can the PH become an upper-middle income country within this lifetime?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-ph-upper-income-country-04052024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=295px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.