SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

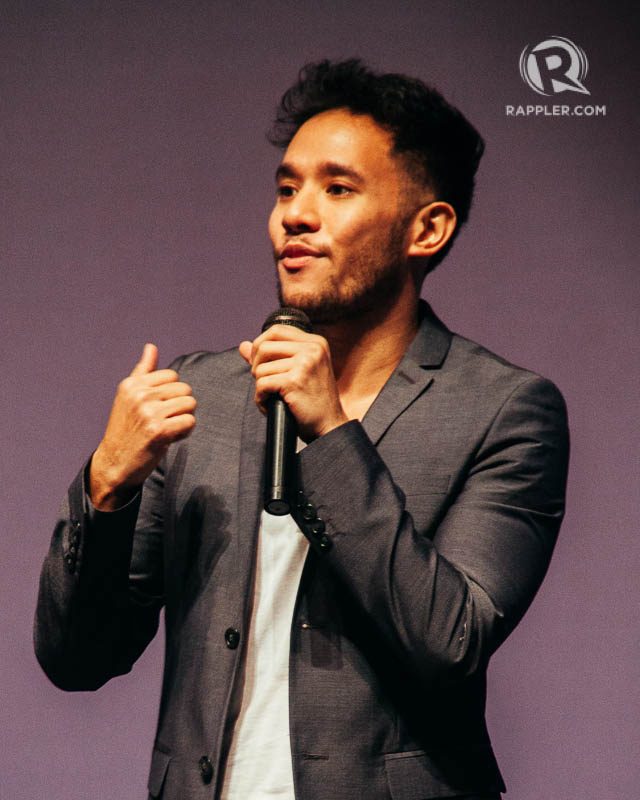

MANILA, PHILIPPINES – Above the Clouds, what director Pepe Diokno calls his “love letter to the Philippines,” has finally come home.

Cinephiles have long anticipated the Philippine premiere of Above the Clouds, but since production wrapped up in the cold highlands of Northern Luzon, the filmmaker and his team have been always on the move.

Because the film is a Filipino-French co-production, Diokno had to spend part of their foreign grants (including the International Relations Arte Prize at the Berlinale Talent Campus and the French government’s Aide aux cinémas du monde) on post-production in Paris.

After 5 years in the making, Above the Clouds embarked on the international festival circuit. In October 2014, the film premiered as an Asian Futures sidebar feature in Tokyo. It also clinched a competition berth in Singapore, held later in December. In both countries, the film received warm reception, especially from the Filipino expats who attended the screenings.

For the first time, Diokno screened his labor of love to a Philippine audience at Cinemalaya last August 8. It was an opportune moment, as it was also his homecoming to the festival since his debut feature-length film Engkwentro premiered in 2009.

Lion of the Future

In a nation frequently wrought by catastrophes, Above the Clouds hits close to home. Diokno particularly started writing the story in the wake of typhoon Ondoy (Ketsana), which devastated Manila with widespread flooding in the same year that Engkwentro was first shown.

Even so, it could just as well be inspired by the tragedies that had followed in recent years, with super typhoons like Pablo (Bopha) and Yolanda (Haiyan) hitting land.

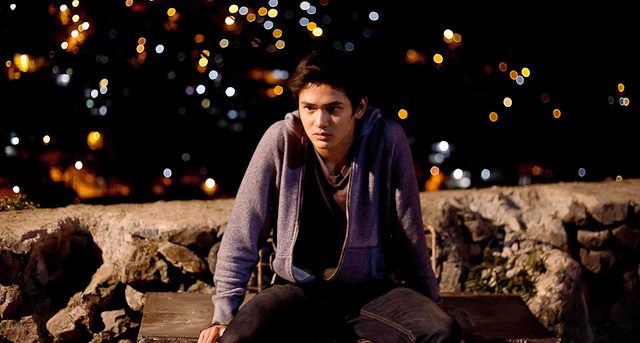

However, the film doesn’t dwell on adversity. Instead, Diokno tells the story of an aloof teenage boy, Andy (Ruru Madrid), who, after losing his parents to the flood, reluctantly joins his estranged grandfather (Pepe Smith) in the north. He sets the two on a trek up and across the mountainous and pine-dotted hinterlands, where both navigate their lives after the deaths of their loved ones.

With the masterful eye of cinematographer Carlo Mendoza, Diokno captures breathtaking vistas of the pair’s surrounding landscape. Moviegoers familiar with Diokno’s work on Engkwentro might highlight this tonal shift from the squalor and edginess of his early gangland thriller.

His critically acclaimed debut, for a while, raised hype that he could be “the next torch-bearer of gritty, urban Filipino cinema,” in the words of The Hollywood Reporter.

Back at the age of 21, Diokno was already bound for the Venice Biennale. After exhibiting at the film festival’s Orizzonti sidebar for new trends in world cinema, he emerged triumphant with the section’s prize as well as the Lion of the Future (Leone del Futuro) – Luigi de Laurentiis Award for Best Debut Film.

Actually, Diokno’s filmmaking can be said to belong to a local tradition of socially conscious and neorealist cinema. Its influential auteurs like Lino Brocka and Ishmael Bernal have a cult following in the international festival circuit. So even today, in the digital renaissance of Filipino cinema, a derelict vision of the Third World persists among global audiences.

In the Phaidon tome Take 100: The Future of Film – 100 New Directors, former Venice Film Festival artistic director Marco Müller featured Engkwentro, and also observed a proclivity for depicting social ills among Diokno and his contemporaries. He wrote, “They are merely rendering what is out there, in a country whose tumultuous history has had lingering painful results.”

Responding to some of the vitriol surrounding his depiction of urban filth, Diokno said, “The film was not dwelling on their situation as being from the slums.” He quickly pointed out the looming presence of vigilantes who carry out summary killings in Engkwentro, and said, “To me, it was an issue about human rights. To me, it was an issue about right and wrong.”

Diokno’s politically charged world view, however, is not solely a product of circumstances. He wields a singularity of vision, inspired by another lion in his kin. Perhaps the spirit of his grandfather, Senator Jose W. Diokno – a renowned human rights crusader and staunch Marcos dissident – lives on in his chosen craft.

After his fêted debut, Diokno admitted that he had feared a sophomore slump. “I couldn’t pick up a camera for an entire year. [I was] coming from a film like Engkwentro, [with] a lot of expectations – a lot of it from myself, a lot of fear about what people are gonna say,” he said.

“Engkwentro was a film that people either liked or hated, and I was 21 when I made that… To deal with all that, [there] was a lot of fear, a lot of burnout… It took a lot out of me.”

Grief, memory, and hope

Diokno mellows in Above the Clouds, and his overtly political outlook takes a back seat. While Engkwentro has been frenetic, his second film gently plays out like a lyrical study on destruction, loss, and ultimately, hope and resilience. (WATCH: Above the Clouds: A video diary)

Even if Above the Clouds has been set in motion by real-life tragedies, Diokno doesn’t preoccupy himself with scenes of total ruin. He goes far away from, say, a Marikina ravaged by floods.

Instead, Diokno creates a composite setting from Mt. Pulag, Baguio, and Sagada (even adding Wawa Dam to the mix), and does justice to these magnificent places with equally arresting imagery. He even jokes about the part that the music of Sigur Rós and Bon Iver has played in his evocative screenwriting.

At the core of a backpacker adventure, he unfolds a family drama.

Like Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011), Diokno juxtaposes his elegy with the grandeur of nature. However, far from being impressionistic, the majestic visuals in Above the Clouds reliably serve Diokno’s narrative.

The writer-director confessed that the source material was close to his own heart. The catalyst, he said, was the death of his grandmother, Carmen “Nena” Diokno in 2011, “I was really close to her, I grew up with her, and […] she couldn’t sit through [Engkwentro] ’cause it was gritty, dark, and magulo (chaotic).” He added, “I really wanted to make this a film that she could watch, but unfortunately, she passed away.”

Above the Clouds is Diokno’s most personal film yet. “For me, it was a way of grieving,” he said. “I couldn’t finish a draft without tearing up myself, and I hope it’s what’s captured in the film.”

The film is an exploration of grief, but it is also an emotional journey for the filmmaker – the same kind that his two characters take.

When Andy is shipped off to his crabby grandfather, who has been alienated from his family for a very long time, he becomes defiant and withdrawn. Diokno said, “Nobody can get through to him – not even a grandfather.”

In the attic of his grandfather’s ramshackle lodge, the teenager stumbles upon pictures of his parents hiking up scenic mountains. The grandfather gets an idea. As if on a pilgrimage, Andy reluctantly follows the old man, in retracing his parents’ steps.

Diokno himself also discovered a trove of photos that his Lola Nena left behind. He reflected, “I realize that when a person dies, it’s not just the person that you lose. It’s also a memory.”

“There’s so many things that [my Lola Nena] left behind that I will never get to hear anymore – stories about my grandfather, stories about the war… And you also lose, sort of, a part of your culture and how you are,” said Diokno.

In a footnote for the film’s stint in Tokyo, he wrote, “When a loved one dies, we always struggle to keep their memory alive, and this idea was central […] in making this film.”

“Grief comes from the thought that we will never be with our loved ones again, and hope comes from the realization that they live on in our hearts for as long as we preserve their memories,” added Diokno. “The journey of the film is a journey between these two ideas, and ultimately, being able to rebuild our lives and find hope amidst despair.”

For Andy and his grandfather, the mourning is more fraught than it seems.

The youngster has become standoffish and wallows in angst. He tries to distract himself – blasting The Strangeness and Gloc-9 through his headphones and constantly fiddling with his cell phone.

The turmoil lies deep within, however: Andy blames himself for his parents’ demise, and beyond this, he sees nothing.

On the other hand, his grandfather, after many years of absence and living like a hermit, tries to warm himself to Andy. At first, he’s a jaded, cheap gin-swilling old man, but he gradually shows remorse for abandoning his family.

However, as he seeks to repair a crumbled past, he’s just fumbling at what isn’t there anymore. He sees everything, but doesn’t see what is right in front of him.

Nostalgia infuses the film – just not the romantic kind. There is a deep sense of regret for a lost past, which “all intertwines,” Diokno said, with the passing of loved ones.

Tribal villages have been abandoned, and urbanization encroaches on the indigenous way of life. Trash is strewn all over the places Andy has seen in his parents’ pictures. In one scene, even the grandfather himself litters and opens a sacred coffin in Sagada (all props).

These images especially irked some members of the mountaineering community, but the director thinks much of the furor, while valid, misses the point.

He explained in a Facebook post, “To me, the grandfather represents the destruction by previous generations. On the journey, he comes to terms with his mistakes.” He contrasts this with the young man, “Andy never touches the mountain. He learns to fear it, respect it, clean it, rebuild it.”

In a way, the mountain acts and looks like a “third character,” as Diokno puts it, because the story, he said, “should be tied to a place.”

The mountain is like a storehouse of countless memories, but there is also something visceral about its appearance. An otherworldly fog ominously shrouds the landscape. Pine trees and caverns eclipse the two pilgrims in size.

It’s as if the sinister but imaginary ghost of the past goes out to haunt the boy and his grandfather, yet on the mountain, something real and special is forged between them.

While the typhoon in the opening scene shows a ruthless side to nature, the mountain witnesses the restoration of bonds. At the summit, their burdens unravel, and the pair is reminded that what matters the most is the here and now. “What we do with what we have left is the question of our film,” said Diokno.

High above an ethereal sea of clouds, the grandfather and grandson – once strangers to each other – finally realize that they are not alone and still have much to live through, with each other.

Lead young actor Ruru Madrid drove this point home, “Pagdating [ni Andy] sa tuktok ng bundok, doon niya na-realize na, ang dami pa palang bagay na natitira sa akin (It was only when Andy reached the summit that he realized, I still have much left).”

An uphill journey

With the film back on home soil, Diokno recalled how “500,000 times more difficult” filming Above the Clouds was. During the making of Engkwentro, he was just a rookie out of film school, learning the ropes of the moviemaking business. By his second film, however, he had more helping hands on deck.

His co-producer Bianca Balbuena assembled a stellar crew that includes cinematographer Carlo Mendoza, production designers Ben Padero and Carlo Tabije, editor Lawrence Ang, and composer Johann Mendoza, among other hardworking folks.

The crew managed to pull off complex set pieces. They had to manage dozens of extras for the evacuation center in the harrowing opening sequence, as well as battle through unruly onlookers along the bustling Session Road in Baguio.

Ascending Mt. Pulag and spelunking in Sagada, while lugging equipment like an Arri Alexa camera and a crane, was also no joke. Diokno said, “Imagine it was a film with two characters, but we were a hundred-twenty people […] behind the camera.”

During post-production in Paris, their French collaborators also brought fresh eyes. For instance, cinematographer Mendoza sat down with colorist Yov Moor, whose portfolio includes the 2010 film adaptation of Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood. Diokno disclosed that Moor had suggested that they overlay film grain and crunch the brightness on Carlo Mendoza’s images, just to make them feel more raw and nostalgic.

“We felt like a family,” Diokno said, as he looked back on the entire experience. “Even if it was the most difficult thing that we did, it was also the best thing that all of us did.”

The filmmaker also struck gold by having on board Filipino rock legend Pepe Smith and up-and-coming young idol Ruru Madrid, who fit the lead roles perfectly.

In a behind-the-scenes featurette, producer Bianca Balbuena revealed that Diokno had written Above the Clouds with Pepe Smith in mind. This tidbit recalled a similar anecdote about how Hollywood filmmaker Sofia Coppola cast the notoriously elusive Bill Murray on Lost in Translation (2003). When Diokno was asked point-blank if he had the same experience, he retorted, “Whether he was gonna show up or not? Yes.”

Diokno pitched his film ideas to several local studios, and they all had a common apprehension – aware of the rock star’s image. The filmmaker came to Smith’s defense by pointing out that the music icon endured grueling call times, dutifully memorized the screenplay (in spite of sparse dialogue), and even hiked up Mt. Pulag until Camp 1. “I believed in him, and there was nobody else in my mind that could have done this role,” said Diokno.

Having only played mostly bit roles in comedies, the veteran musician went through several days of acting workshops. Diokno shared, “I spent [about] two days with Piyaps [Pepe] talking about his life: his relationship with his father, relationship with his children, and that went into his character.”

The results on screen caught even the director by surprise. “It’s a different side of him that I’ve never seen,” he said. At the same time, the grandfather is like an alternate but authentic version of Pepe Smith: a drunkard with a Mick Jagger-like gait, who can actually become a genuinely caring grandfather to Andy (According to Smith, Madrid even vaguely resembles his son Bebop).

Meanwhile, Ruru Madrid had to go through auditions, but he impeccably took up his character Andy’s reclusive persona. Diokno expressed his admiration, “He’s such a good, learned actor, [such that] he can draw up an emotion in the snap of a finger.”

Apart from the personality quirks that Madrid shares with Andy, he revealed that he also went through the same ordeal as his character. He recalled, “Na-experience ko talaga yung Ondoy, and ‘yon siguro yung part sa buhay ko na never ko talagang makakalimutan dahil sobrang hirap. (I’ve experienced Ondoy, and I will probably never forget that part of my life because it was so difficult).”

Madrid got into the zone with the help of some method techniques imposed on him. Diokno said, “Totoo yung emotions niya (His emotions were authentic), so it was nice to have him and Piyaps [Pepe Smith]. ‘Cause Piyaps is not a learned actor, and he was so unsure about what he was doing.”

“So, they had two different acting styles, and you see it in the film,” the director illustrated. “Together, they clash, which is what their characters are supposed to do.”

Diokno launched a nationwide series of pop-up screenings for Above the Clouds at the UP (University of the Philippines) Cine Adarna last September 5. The film is set to make its television premiere on March 25 on GMA-7.

He has been engaged with directing the offbeat rom-com series Single/Single on cable channel Cinema One. In October 2015, he returns to form with the QCinema film festival entry Kapatiran, which focuses on the power plays within a law school fraternity.

Now that Above the Clouds can hit screens across the country, Pepe Smith, with his signature “rakenrol” swagger, said, “Nakahinga ako nang maluwag. Para akong nabunutan ng sibat. Hindi ng tinik, pare, sibat ang nabunot sa leeg ko! (I heaved a sigh of relief. It was like a spear had been yanked out of me. Dude, not a thorn, but a spear was pulled out of my neck!)”

After the Cinemalaya screening, Diokno said, “It’s the peak of our journey, [that] we can finally find an audience at home, and I hope that people have a space for the film in their hearts.”

– Rappler.com

Paolo Abad is a film/television editor and motion graphic designer. He is also a self-confessed concert junkie – a perennial attendee at gigs of indie acts.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.