SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Cinemalaya 2017 is now in full swing, and audiences are trooping to theaters at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) and other pocket venues to catch all the new local films by independent filmmakers. Nine full-length films are competing in this year’s festival. Here’s what movie critic Oggs Cruz thinks of each one:

‘Ang Guro Kong ‘Di Marunong Magbasa’ Review: More damning than inspiring

The silver lining in this otherwise rusty advocacy film is that its final 15 minutes may be one of the most outrageous displays of rage and frustration over the government’s lack of effort to address the problem of lack of education in more remote areas in the country. Writer and director Perry Escaño drapes his awkward and unsophisticated debut Ang Guro Kong ‘Di Marunong Magbasa with crass sentimentality, that parts of it play like sequences straight out of an afternoon soap. But he suddenly shifts gears, turning his mostly saccharine film into a horrifying display of brutality that weirdly feels justified, even if so much of it is committed by children.

Make no mistake. This is by no means a defense of the entire picture, which is plainly atrocious. Ang Guro Kong ‘Di Marunong Magbasa is bogged down by a screenplay that seems to reject the art of subtlety, forcing its characters to mouth expositions with an emotional intensity that leaves no room for the imagination. It also suffers from overwrought performances, the most glaring of which belongs to Alfred Vargas, who plays the titular ignorant but selfless farmer-turned-teacher the same way he plays the ignorant but selfless gigolo-turned-insurance salesman in Jeffrey Jeturian’s comedy Bridal Shower (2004).

All the senseless histrionics could have done wonders if Escaño intended for his film to be a comedy. However, the film is clearly meant to be taken seriously. It endeavors to relay a message that admittedly deserves to be heard, except that it does so without a sliver of elegance or clarity, resulting in something so skewed, it may prove to be more damning than inspiring. Escaño can’t claim to justify his film’s faults with all the good intentions he has. Sure, the film was borne out of a very worthy advocacy, but when its most effective scenes are the ones where it seems to strangely promote vengeance, vitriol, and violence, its message of hope and perseverance simply gets lost in the hilarity and the fray.

‘Ang Pamilyang Hindi Lumuluha’ Review: Silly banter over sense

Essentially a parable purposely bloated to make way for some sitcom hijinks, Ang Pamilyang Hindi Lumuluha is an intriguing but failed attempt to merge director and writer Mes de Guzman’s practical and sometimes compelling but low-rent aesthetics with farcical banter. At worst, it is quite incomprehensible, a work that neither achieves its goals of entertaining _ through the grooves of comedy made familiar by its abundance in free television – or relaying any emotions that are truly heartfelt.

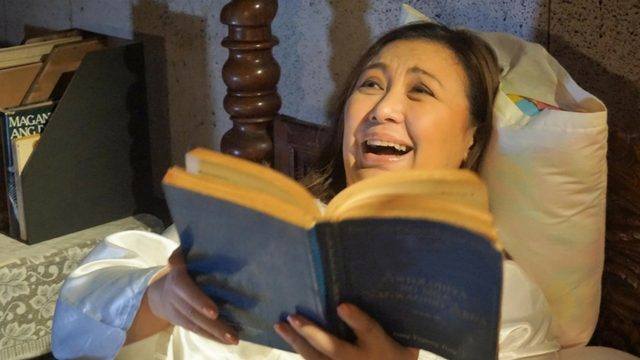

De Guzman is no stranger to installing pop culture icons into his obscure narratives. His Ang Kwento ni Mabuti (2013) had Nora Aunor play a faith healer who finds herself in a moral predicament. While Aunor played her part expertly, the film ultimately suffered from the fact that Aunor is too conspicuous a presence in a film that is rough around the edges. In a way, Ang Pamilyang Hindi Lumuluha occupies the same territory of De Guzman cleverly utilizing the celebrity of his lead to ground or add layer to his themes. De Guzman, this time, populates his film not with non-actors, ensuring that there is no disparity between the performances. Sharon Cuneta, who plays a lonely woman who seeks to find all the members of the titular family to help her complete her own estranged family, lends believable levity to the character. Her humorous repartee with Moi Marcampo, who plays that lonely woman’s maid, is really the meat of the film.

Unfortunately, the incessant banter tarnishes the parable’s heft to the point that as soon as Cuneta lets go of being a clown to reveal her character’s dramatic longings, it feels too late and too distant to be really effective. Ang Pamilyang Hindi Lumuluha suffers from being a concept that feels right on paper but is all sorts of wrong upon execution. Its inventive take on the family sitcom just falls short. It never really evolves enough to make sense of its offbeat marriage of silly antics and anything substantial it wants to communicate.

‘Baconaua’ Review: Indecipherable puzzles

Like his Nuwebe (2013) with its story of a pregnant 9-year-old girl, Baconaua has director Joseph Israel Laban again exploring current and controversial themes through local folklore. Set in a closely knit fishing village in Marinduque, the film details the lives of 3 siblings right after their father, a sea patroller, has gone missing for several weeks. The folklore element comes by way of the titular sea monster, which according to legend, tried to swallow the moon. The creature here takes its vague place alongside a slew of other bizarre events that slowly creep their way from being objects of faith and mythology to make sense within the film’s current universe of familial strife and social corruption.

The disparate elements of Baconaua never really cohere in a satisfying manner. The film is paced pensively, almost in an effort to hypnotize its audience into some supernatural stupor. There is also the Jema Pamintuan score that adds enigma to the images cleverly composed by cinematographer TM Malones. Clearly, Laban endeavors to form a palpable atmosphere to add further layers to an otherwise straightforward story, yet the result is a film that is sorely muddled by jarring – though provocative – ideas. There are sadly no emotions to the exercise. Despite the compelling performances of both Elora Espano and Therese Malvar, who play sisters whose relationship is tainted by a local boy who they both fall for, the film is far too opaque to be of any real effect.

Baconaua could be about a lot of things. With its curious use of the Philippine national anthem sung in both Spanish and English, it could be about how the country’s colonial past mirrors the sordid relations the various personalities residing in the fishing village have with each other. With its scenes involving apples and serpents and narrative movements that involve sexual tensions and other temptations, it seems to be reflecting on biblical themes, or at least drawing on the primal power of Christian imagery to add impulse to its moods. It is all compelling on paper, except that it only functions to turn the film into an indecipherable puzzle instead of a true cinematic experience.

‘Bagahe’ Review: Meandering for mercy

It’s a clever touch that the main character of Zig Dulay’s Bagahe is named Mercy. From the film’s first frame down to its last, she begs for it from both the characters around her and the film’s audience.

The film opens with Mercy, whom we don’t see but only hear, due her panicked breathing inside an airplane’s cramped bathroom. We later find out from the news that a baby was found in the airplane’s trash, alongside a rosary, prompting the concerned country to name her Rosario. From there, Mercy, who we first see enjoying a reunion with her family, is forced to undergo medical procedures, gets hounded by media, and is ultimately housed in a social services home for troubled women. Bagahe avoids the tempting melodrama that could have resulted from the intriguing and controversial premise to traverse a less exciting route, all in the efforts of exposing the ills of bureaucracy from the distinct perspective of women who both victimize and are victimized.

There are many very interesting touches here. Bagahe is populated by all sorts of women in power, all with varying degrees of concern for Mercy, from the clinical disconnect of the lady doctor who checked her for signs of pregnancy to the suspicious involvement of the senator who publicly announces the real story behind her pregnancy. It seems that Dulay is mapping a peculiar society, where women are both free to be whatever they want to be but are also constrained – occupying roles and satisfying expectations. The film’s thesis is meritorious. Sadly, Dulay’s approach is far too reliant on Angeli Bayani’s very proficient portrayal of Mercy to really emotionally connect, resulting in a film that meanders for too long to arrive at any worthy meaning.

‘Kiko Boksingero’ Review: Pure, simple and truly lovely

There is a sparseness in Thop Nazareno’s Kiko Boksingero that is surprisingly soothing.

The film only has 3 major characters: Kiko (Noel Comia, Jr), the boy who quietly pines for a father figure, Kiko’s dad (Yul Servo), a retired boxer who finds himself back in Baguio City for some undisclosed reason, and Kiko’s guardian (Yayo Aguila), a doting woman who tries her very best to raise Kiko after the death of his mother. The film follows a very simple narrative. Kiko, after learning of his dad’s return, starts a daily pilgrimage to his dad’s home after school. There, he starts to learn how to box just like his father. Nothing much else happens. There are occasional encounters with bullies in school, teasing him for the fact that he is both uncircumcised and lacking a father. He also has a crush. The film, however, doesn’t complicate itself with those extraneous stories. They are but details to the pervasive mood it so efficiently establishes.

It is easy to praise Kiko Boksingero for its simplicity. Sure, it is essentially the coming-of-age story of a boy who has been raised first by a sickly mother and then by a gentle nanny. However, beneath its mellow charms and elegantly depicted quirks is a sublime portrait of a childhood that is rendered incomplete by society’s expectations of what proper masculinity should be and the immaturity of a man who perceives fatherhood not as a duty but as a mere hobby. Instead of pushing for manipulative plot points, Nazareno focuses on his protagonist’s fervent desire to break routine, both as rebellion to how his life is being managed for him by women and as part of his uncertain path towards manhood. As a result, the film feels fresh even if the message relayed is comfortingly familiar. Kiko Boksingero is such a pure film. Its pleasures are abundant, and its heartbreaks, while laid out in the softest way possible, are all profoundly felt.

‘Nabubulok’ Review: Crime and suspicion

It only takes the minutest of details to ruin a perfectly fine film. In the case of Sonny Calvento’s Nabubulok, it took a minute’s worth of end titles – which described the fates of the characters of his true-to-life crime story and the veracity of the mystery that drives the film – to break its bizarre charm.

Nabubulok opens at night with a farmer witnessing an American (Billy Ray Gallion) and his teenage son (Jameson Blake) suspiciously doing something from afar. The following morning, the duo goes to a hardware supply shop to purchase a bag of cement. They proceed to go home, where a neighbor (Gina Alajar) is nervously waiting, complaining of a foul stench coming out of the American’s gated compound. Throughout the film, Calvento expertly concocts just the suspicion that a crime has been committed. He neither confirms it nor denies it, and instead ingeniously tells the story through the doubts and conjectures of everyone close to the American’s family. In a way, Nabubulok projects a nation’s sometimes valid and also sometimes imagined sentiment against America, or foreigners in general. It is a film that provokes distrust by virtue of difference in culture. This is a film that fluently echoes alienation, whether deserved or not.

It is also quite fascinating that the only crimes that Nabubulok shows onscreen are the ones committed by Filipinos. In some weird sense, it almost feels like Calvento is exposing not the sins of the foreigners but the faults of the locals, with their propensity for quick judgments and rumor-mongering. Despite the film’s insistence on being too obvious with its many metaphors, with its jarring color motifs that recall the primary colors of the Philippine flag, it mostly works when it comes to portraying a fractured culture that teeters towards isolationism. In that sense, when Calvento decided to completely abandon the mystery of whether or not the American deserves his fate, he transformed his film from a comprehensive expression of anti-American sentiment into a just an ordinary crime thriller.

‘Requited’ Review: The predictable road to nowhere

The best thing about Nerissa Picadizo’s Requited is that it is competently crafted. It is also the worst thing about it. This isn’t a film whose elements are so bad, the entire thing is good. It’s just a film that plods along ponderously until its very last moments, when the story steers away from its predictable but burdensome course to be a little bit interesting all at the expense of logic and sense.

Its most striking sequence is right in the beginning, where we see Matt (Jake Cuenca) biking his way from the busy highways of Metro Manila to the provinces. Save for a few moments where Chi Capulong’s score swells to supposedly communicate the character’s inner turmoil, the sequence follows a coherent geographical direction. Unfortunately, the film, which hopefully could have followed its opening’s coherence, is incoherent in terms of its emotional trajectory. It is a romance that befuddles and confounds. It is mostly a frustrating experience, a film that purports to convey the profound repercussions of a failed love but only succeeds to enunciate the unintended hilarity of its all of its silly coincidences.

It also doesn’t help that the two characters at the heart of Requited spend most of the film arguing. Matt is an impenetrable and cynical presence, while Sandy (Anna Luna), presumably Matt’s former flame, comes off as needy, with intentions that are puzzling at best. In between lengthy scenes of the two biking in the countryside, the two characters are too busy establishing a connection that never really concretizes. It’s quite a pity, really.

‘Respeto’ Review: The power of words and rhythm

There is one scene in Treb Monteras II’s Respeto that sums up its compelling paradoxes. The scene involves Hendrix (Abra) lamenting how he was not able to do anything when he saw his romantic interest (Kate Alejandrino) being raped by his rival (Loonie). Doc (Dido dela Paz), retired poet and activist during the Marcos regime and now Hendrix’s surrogate mentor, proceeds to tell his own experience of being powerless in the face of abuse, how he witnessed his own family being exploited by government thugs, how he got his revenge by smashing one of the abusers’ faces with a rock, and how his brutal act ultimately felt empty.

It’s a poignant scene, one that works in the way it establishes the complicated relationship between a mentor and his mentee through shared tragedies. It also expresses how both Hendrix and Doc are reduced to inutility in the face of atrocity and how Doc, a master of using words, resorts to violence to fight back. Respeto is set in a subculture most predominant in impoverished areas, where the power to weave both words and rhythm is power. Instead of putting that subculture on a pedestal where it is seen as a symbol of hope, it limits it by giving it a historical perspective, a role in a society where words have both triumphed and failed in its effort to arouse change.

Respeto is really a coming-of-age film, but unlike most other comings-of-age, the maturity that Hendrix achieves in the end is laced with savagery. It is a film whose mood and designs are bravely current, most likely inspired by the culture of inhumanity that is being perpetuated by the present leadership’s landmark policies. It regrets how, in such a world of strife, words are used to incite petty divisions and shallow insults instead of creating proper discourse. The film’s ending, an arresting and indelible tableau that completes the film’s call for action, is bereft of beats and clever words. It is all exquisite bleakness, a portrait of words falling and failing resulting again in an act of violence that is both warranted but empty. Everything’s a vicious cycle when impunity is an element of our culture.

‘Sa Gabing Nanahimik ang mga Kuliglig’ Review: Bleak religion

The abundance of Catholic imagery in Iar Arondaing’s Sa Gabing Nanahimik ang mga Kuliglig is disquieting, precisely because the film’s narrative of sordid relationships and crimes of passion, feels like it is set in a godless world, where faith is inutile and Christian virtues are but myths amidst a world drowning in sin. The film’s use of the 4:3 frame allows it to populate its scenes with empty spaces, evoking a palpable sense of estrangement from any form of salvation that religion promises.

Arondaing populates his film with characters in crisis, all trying to make sense of their own moral fragilities amidst an abundance of supposed spirituality. It is compelling when everything works, when the consistently fine acting melds seamlessly with Arondaing’s curious aesthetics. It is just that this sort of ingenious exposition feels too familiar, given that Philippine cinema has produced tons of stark commentaries on a society whose appreciation of religion seems skin-deep. It’s quite an intriguing setup, one that makes one wish that the film endeavored to be more than just the showcase of bleak ironies that it is. – Rappler.com

Francis Joseph Cruz litigates for a living and writes about cinema for fun. The first Filipino movie he saw in the theaters was Carlo J. Caparas’ ‘Tirad Pass.’ Since then, he’s been on a mission to find better memories with Philippine cinema.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.