SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

In the final few minutes of Todd Haynes’ Carol, we see Therese, the department store clerk played by Rooney Mara, entering a very busy restaurant.

She is overwhelmed by the crowd, a mixture of well-dressed patrons walking about or conversing animatedly with each other. She walks around, in search of someone. She finds Carol, her former lover played by Cate Blanchett, at the other end of the room, busy exchanging delightful stories with her friends. Carol sees Therese from afar. Haynes’ camera slowly zooms on Carol’s face, now removed from the noisy restaurant, intently staring at Therese who we presume is also looking lovingly at her. Their passionate and knowing glance, the only connection that they share in a space full of strangers, ends with Carol offering a comforting smile.

Beautifully converging

That scene in Carol exemplifies Haynes’ skill in evoking a sense of space between his characters.

In just a matter of seconds, he creates a sea of diverse people, jarring classes, of social awkwardness, and history that inevitably separate the two characters who we have come to believe are in love. In that same time period, he was able to direct a telling gesture that wipes away the literal and symbolic distance between the two, establishing with such subtle but still intense emotional force a profound connection. It’s just absolutely beautiful.

Think of Wonderstruck as an expanded version of those precious final minutes of Carol with its two storylines set in different timelines and occupying the dominant cinematic aesthetics of their respective eras beautifully converging in the end.

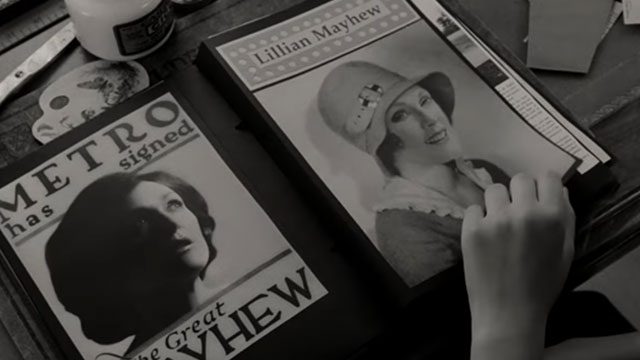

In the ’70s, a young boy (Oakes Fegley), who in a series of unfortunate events loses his mother to a road accident and his hearing to lightning, travels to New York City to look for his father. In the ’20s, a deaf-mute girl (Millicent Simmonds) from Hoboken escapes her stern father and takes a ferry across the Hudson to New York City to locate her mother (Julianne Moore), a movie star who has a production in Broadway.

Haynes orchestrates the two narrative threads seamlessly, allowing an episode from each era to bleed its cliffhangers and emotional turns into the other era, never letting go of the unbroken flow of suspense and energy.

Meticulous crafting

Haynes’ crafting is still as meticulous as ever.

Haynes has always been a director that succumbs to the allure of minutiae that pinpoint forgotten eras. Carol isn’t just a showcase of period preciseness but its mood and elegance enunciates the time-bound seductiveness of forbidden romance. Velvet Goldmine (1998) Far From Heaven (2002), portions of I’m Not There (2007) reveal a director who does not only revel at attitudes and ornaments from yesteryear out of fleeting infatuation, they reveal an artist whose aesthetic allegiance teeters drastically towards the past.

In Wonderstruck, he lovingly seasons each narrative thread with all the particulars that transport his audiences back in time. From the eyes of the girl, ’40s New York City is a labyrinth of busy pedestrians, unperturbed from their daily business. The same city in the ’70s is blistering in both heat and color. It is chaotic, dangerous but severely inviting. Haynes celebrates both the change and the stubbornness of the metropolis.

In a sense, his reimagining of both the ’40s and ’70s have the appeal of dioramas, pint-sized recreations of particular moments frozen forever for the nostalgia-fueled enjoyment of the current world. Haynes’ film is one where dioramas have a pertinent role in weaving together disparate plot points and their momentarily lost characters.

Magical portals

The film evokes that very magical sense of crafted works serving as portals that elude both space and time.

When both the boy and the girl from their respective storylines and eras finally meet, the emotional impact is simply undeniable. Haynes allows the drama to peak with the marriage of exposition and masterful visual sleight-of-hand. He weaves an unlikely magic out of a melodramatic reunion, reminiscent of the same way he turns two lovers’ impassioned glance across a crowded restaurant into a romantic conversation that is worth volumes. – Rappler.com

Francis Joseph Cruz litigates for a living and writes about cinema for fun. The first Filipino movie he saw in the theaters was Carlo J. Caparas’ Tirad Pass. Since then, he’s been on a mission to find better memories with Philippine cinema.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.