SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

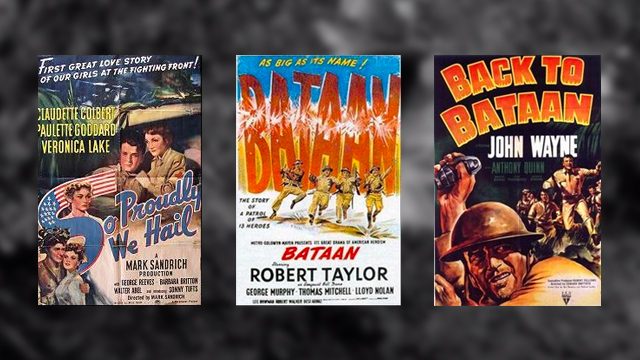

As we celebrate this year’s Araw ng Kagitingan (Day of Valor), let us go back to the time when Bataan was an important Hollywood theme for movies. Like other Hollywood films then, Bataan was an effective theme to impress upon the viewing public what the government wanted. Elmer Davis, Director of the Office of War Information (OWI), was first to recognize these possibilities. He stated that “the easiest way to inject a propaganda idea into most people’s minds is to let it go in through the medium of an entertainment picture when they do not realize that they are being propagandized.” Hollywood and the rest of the entertainment industry became an integral part in stimulating patriotism and morale, including the events that took place in Bataan.

An early film on Bataan came out in September 1942 with OWI collaborating with Paramount Pictures to produce a “Victory Short” propaganda film entitled A Letter from Bataan. The short features two American soldiers in the jungles of Bataan when a bomb drops, killing one of the soldiers, and wounding Johnny. Johnny, on his death bed, writes a letter begging his family back home to ration and conserve to prevent the death of soldiers in the field due to lack of materials and food. A Letter from Bataan is part of a series of films made by Paramount Pictures to encourage the American public to participate in the war effort.

Bataan

The first Hollywood wartime movie with Bataan as a theme was produced in 1942, before the first year anniversary of the attack on the Philippines. At the urging of the OWI, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) released Bataan in 1943. MGM began discussing the movie with OWI as soon as the Bureau of Motion Pictures opened in Hollywood and its script submitted in 1942. The OWI praised Bataan for showing “a people’s army fighting a people’s war,” “makes an especially good contribution,” and “should be given an export license.” The film, shot entirely in a studio, was released in the US on June 3, 1943.

The movie is a fictionalized account of 13 Americans tasked to prevent the Japanese army from crossing a bridge to Bataan. The mixed group of army, navy, and air force personnel consisting of African-American, Hispanic, Filipino, and other nationalities hold its ground against the advancing superior Japanese force. As each soldier meets his end, the camaraderie and trust between the soldiers are strengthened. In one of the scenes, a young sailor writes a letter to his mother which appears to be a homage to the soldiers who served in Bataan:

It’s too bad some of the other men I came here with had to get killed. Maybe it don’t seem to do a lot of awful good young men getting killed in some place you never heard of, probably never will. but we figure that the men who died here would have done more than we’ll ever know. Save this whole world. It’s like Corporal Juan Katigbak said. He said it don’t matter where a man dies as long as he dies for freedom.

Juan Katigbak was played by a Filipino actor Roque Espiritu. Another Filipino actor in the movie, Jose Alex Havier, played Yankee Salazar. Among the band of soldiers, Havier’s character was the most ardent believer that the help promised by MacArthur was on its way. Both characters died gruesome deaths – Katigbak stabbed from behind with a samurai sword and Salazar hanged on a tree.

Bataan is quick to stir the emotions. The opening credit announces that the defenders of Bataan, the immortal dead, heroically stay the wave of barbaric conquest and buy 96 priceless days with their lives. This conveniently played in the narrative that Bataan was a strategy to delay the Japanese onslaught. Bataan also mirrored the steadfast belief of Filipinos in the American promise of deliverance. It also focused on the idea of Bataan as a triumph of American heroism, not an ignominious defeat.

Bataan’s ending credit hails the sacrifice in Bataan that made possible US victories in the Coral and Bismarck Seas, at Midway, on New Guinea, and Guadalcanal.

With Bataan, everything that the cinema has to offer is placed in service of the main message of propaganda. With the release of Bataan, the formula for World War II combat films was set in place.

So Proudly We Hail

In September 1943, Paramount released So Proudly We Hail, also known in the US as “the first great Love Story of our girls at the fighting front!” Billed to be the most stirring drama ever lived by American women, the movie is filled with characters of ordinary American women who, in the desperate hour of the country’s need, “rose to magnificent heights of courage no woman and few men have ever reached before.”

So Proudly We Hail! follows the adventures and hardships of a troupe of military nurses. It takes them from December 1941, with their Hawaii-bound ship diverted to Bataan after the attack on Pearl Harbor, through Corregidor and finally back to the US about a year later.

‘Cry ‘Havoc”

Another movie based on the experience of nurses in Bataan was released by MGM in November 1943. Cry ‘Havoc’ stands as a testament to the heroism of American nurses during the Pacific Campaign. Cry ‘Havoc’ is set in a Bataan bomb shelter during World War II and relates the story of 9 nurses while waiting out an imminent Japanese attack. The film is typical of the pro-American propaganda. It emphasizes Japanese brutality by including a scene where an American nurse is machine-gunned by an enemy fighter pilot while bathing in a stream. At the same time, the movie is a message of defiance with one of the nurses promising, “We’ll get him, we’ll get every mother’s son of them!”

In both So Proudly We Hail! and Cry ‘Havoc’, the meaning of the war was shifted to issues of love, motherhood, sex, and choice. Still, both were on point in their settings to rouse the women towards the cause of the war.

Back to Bataan

As the war drew to a close in 1945, another picture was released by RKO Radio Pictures in May. Back to Bataan starred John Wayne as an American colonel who establishes his guerrilla resistance after the fall of Bataan. His rag-tag crew of Filipinos harasses Japanese units until the Leyte landing takes place. The film acknowledges in its opening credit the cooperation of the US Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard, and the Government of the Commonwealth of the Philippines.

With the war reaching its conclusion, production had to include some of the recent developments in the war front. Footage of the Leyte landing in October of 1944 was included and the liberation of the Cabanatuan war camp in January 1945 was reenacted to herald the introduction of real prisoners of war freed by the siege. The Cabanatuan siege was used as the take-off point to draw out the crowd and lead them back to Bataan where it all began.

Colonel Madden (Wayne) is ordered to remain in the country to organize a resistance unit until the return of American forces. While on their way to Mariveles in Bataan, his party witnesses the Death March. When news of the fall of Bataan reaches the main party, disbelief reigned. The Filipino members of the guerrilla unit are quick to question the turn of events. “Seventy thousand men, how could it happen?” they ask.

This is the part where the movie took to explaining how Bataan fit the narrative of the indomitable spirit of resistance and heroism that were present in Bataan. This scene reminds all viewers that Bataan was never a resounding defeat, only a temporary loss. It tries to answer the nagging questions one may still have until now of the 1942 American strategy in the Philippines.

“The hunger and sickness beat us, not the Japs,” is the quick reply. “Then why didn’t America send food and medicine? Why didn’t America help?” All faces turn to Colonel Madden who is gently advised by the Filipino sergeant to get away and save himself now that the fighting is in Australia.

“Maybe there will be fighting here, maybe the people will wanna fight,” replies Colonel Madden as he hands a bolo to a Filipino. “Sure the people will fight,” says the sergeant heartily. “Against thousands of Japs, after they’ve beaten our armies?” asks a doubting guerrilla. “We have fought that way before, we have never been conquered?” assures the sergeant. “We must have a hope. We cannot die for nothing.”

At this juncture, Wayne’s character calls on the name of a Filipino hero during the Philippine revolution against Spain in 1896. He asks if the guerrillas remember the name Andres Bonifacio and if he were alive and sent out a call, would the guerrillas respond? After hearing that every Filipino knows Bonifacio, he pleads with them to find Bonifacio’s grandson among the Bataan prisoners. The Filipino guerrillas respond in unison, “Hanapin natin at iligtas natin siya (Lets find him and save him).”

Back to Bataan makes references to other Philippine heroes. The American teacher recites General Gregorio del Pilar’s last entry in his diary before he was overcame by Americans in the battle of Tirad Pass during the Philippine-American War.

Principal Bello exclaims: “I am surrounded by fearful odds that will overcome me and my gallant men. But I am well pleased with the thought that I die fighting for my beloved country. Go you into the hills and defend it to the death.” After his delivery, the Japanese soldiers come barging through the door. The hills could very well refer to the hills of Bataan and the battle, no longer against the Americans, but with the new invaders – the Japanese.

Principal Bello says that America taught the Philippines “that men are free or they are nothing.” When the Japanese order him to lower the American flag, he resists and is hanged in its place. His death is soon avenged and his epitaph bore the passages from Rizal’s Mi Ultimo Adios. As the camera pans in on the grave, the Philippine national anthem plays in the background.

No matter how loose the treatment was, Back to Bataan gives credit to the Filipino guerrilla movement in keeping the war front active against the Japanese. Its use of the memory of Filipino resistance against the Americans to call for struggle against the common enemy of the period – the Japanese – was a carefully monitored propaganda of Hollywood’s wartime genre.

They Were Expendable

Another John Wayne starrer that touched upon Bataan was the MGM movie released in December 1945, They Were Expendable. Originally conceived by MGM and the US Navy in 1942 as a vehicle for wartime propaganda, They Were Expendable began filming only in 1945. The movie was based on the defense of the Philippines from December 1941 through April 1942. The book was a national bestseller in 1942 and offers an account of the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Three’s heroic actions during the disastrous Philippine campaign.

One of the scenes featured the announcement of the fall of Bataan over a radio – WBKR San Francisco. The announcer, after apologizing for a brief interruption, read a spot and tragic report from the Philippines.

The white flag of surrender was hoisted on the bloody heights of Bataan this afternoon. Thirty-six thousand United States soldiers, hungry, ragged, half-starved shadows, trapped like rats but dying like men were finally worn down by 200,000 picked Japanese troops. Men who fight for an unshakeable faith are more than flesh. But they’re not steel. Flesh must yield at last. Endurance melts away, the end must come. Bataan has fallen. But the spirit that made it a beacon to all lovers of liberty will never falter.

When OWI saw the script, the office raised no objections. The movie would serve as an outstanding contribution to the government’s war information program.

From Bataan to Sahara

Bataan’s effect on cinema went beyond films that took it as main fare. In Sahara – a movie dedicated to the IV Armoured Corps of the Army Ground Forces of the United States Army released in November 1943 starring Humphrey Bogart – Bataan was more than a simple encouragement.

When a German scout car appears in the horizon, the party captures two soldiers. Bogart’s Sergeant Gunn manages to break one to provide information by teasing him with a cup of water. Upon learning that a thirsty mechanized battalion of about 500 men is some 70 miles away and had no water for days, Sergeant Gunn summons the men with his against-impossible-odds speech.

“If we did get back there, they might even give us a medal. If we stay here maybe nobody will ever know what happened here. Or if it is worthwhile or if it is all wasted,” says Gunn. “Still it’s the obvious duty of every man in the armed forces to do everything he possibly can,’ says another. Gunn explains that the 100-1 shot situation gives them little chance of coming out alive. “Well, nobody minds giving his life, but this is throwing it away. Why?” asks one.

Here, Gunn asks the soldiers in the same way he’s asking the audience. “Why Bataan? Why Corregidor?” Gunn convincingly argues that those who fought in Bataan and Corregidor may all be nuts but there was one thing they did do – they delayed the enemy and kept on delaying them until the US and her allies would be strong enough to hit the enemy harder than he was hitting.

To delay, to buy time, until the Allies can be strong enough to beat the enemy was a “timeworn battlefield pep talk to induce volunteers for a suicide mission,”

wrote Theodore Kornweibel Jr. The Bataan speech works because everyone remembers Bataan and Corregidor, not only Gunn’s men but all the American audience in the theaters as well. The scenes depicted the fight over several waves of attack, each time reducing the number of defenders, like in Bataan.

In conclusion, as a Hollywood theme, Bataan proved a hit with 5 films exploiting the narrative of defiance amid insurmountable odds. The involvement of Filipinos in the war was given ample treatment. Aside from being highly entertaining and profitable, the movies instilled in their American audience pride in their troops. The movies were effective in “renewing faith in the worth of the war sacrifice’ and made the ‘cathartic experience more acceptable.” The movies rallied patriotism, induced the purchase of war bonds and reaffirmed American values at a time of great national challenge. – Rappler.com

A former media affairs director at the Department of Foreign Affairs, Geronimo Suliguin Jr is a historical studies postgraduate student at Oxford University. He earned his master’s and bachelor’s degrees, both in history, at the University of the Philippines in Diliman.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.