SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Alyx Ayn Arumpac’s award-winning documentary Aswang is free to stream from Saturday, July 11, 6 pm, to Sunday, July 12, 11:59 pm.

The documentary, originally set to premiere during the Daang Dokyu Festival last March before being postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, chronicles the first 3 years of President Duterte’s drug war through stories of ordinary people caught up in the campaign’s bloody path. These include a missionary brother who comforts the families of victims and a street kid who was close friends with Kian delos Santos, a 17-year-old student murdered by 3 policemen in 2017.

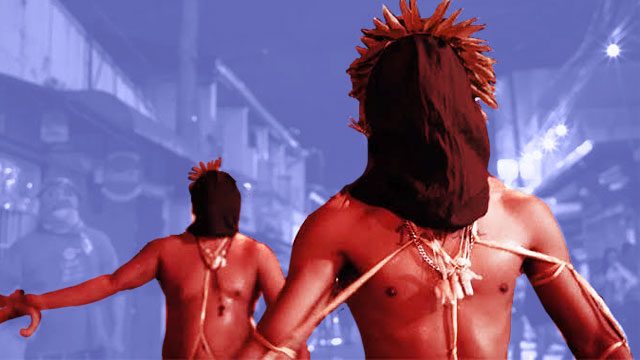

Compared to documentaries that either capture the Philippines’ drug war from a Western perspective or have an international audience in mind, Arumpac’s documentary goes for a deep Filipino treatment. It uses the myth of the aswang as its throughline, imbuing the film with dark, magical realism. Scenes are punctuated with an almost lyrical delivery of lines that often start with the words “Kapag sinabi nilang may aswang, ang ibig sabihin nila: matakot ka.” (Whenever they say there is an aswang around, what they really mean is: be afraid.)

Aswang blurs the lines between the myth-building that has made these supernatural monsters a device historically used to keep children at bay and the all-consuming atmosphere of dread brought about by state terror.

Aswang is quite a lot to take in. To help you process and get a better grasp of everything shown in the documentary, here are Rappler articles which could help contextualize things:

As mentioned above, Arumpac uses the aswang mythos as a creative device in chronicling the horror the administration has wrought in the first 3 years of the drug war. In this opinion piece, veteran award-winning feature writer Sylvia L Mayuga argues that understanding the milieu via the lens of folklore is inherently part of the Filipino worldview. She delves into the deconstruction and reconstruction of aswangs from rural myth to CIA counter-insurgency tool to its wide-spread use in pop culture.

Our son, Kian: A good, sweet boy

Aswang features an ensemble of characters who’ve found their lives entwined with the administration’s war on drugs. However, arguably, there are two main characters most of the film centers on. One of them is the young but already world-weary street kid, Jomari.

Jomari is introduced on-screen as he mourns the death of Kian, his surrogate kuya and– as he describes him– “his only friend in the world”.

On August 16, 2017, the 17-year-old student was shot to death in what the police described as an encounter in a dark alley near Kian’s house. His last words: “Tama na po, may test pa ako bukas (Please stop, I have a test tomorrow).”

In this profile, the family and neighbors of Kian Loyd delos Santos ask: Why in the world would police kill such a sweet boy?

TIMELINE: Seeking justice for Kian delos Santos

On November 29, 2018, the Caloocan Regional Trial Court Branch 125, found 3 Caloocan policemen guilty of murdering Kian Loyd delos Santos.

The conviction came more than a year after delos Santos was gunned down in August 2017. According to police, he was killed in an encounter, but CCTV footage and witnesses revealed that he was dragged to a dark alley and shot.

Delos Santos’ death triggered massive condemnation of President Rodrigo Duterte’s violent war on drugs. This is a timeline of key events on the 6-month trial that led to the conviction.

Duterte’s violent drug war leaves children traumatized – HRW

Jomari is just one of the many children scarred by the death of a loved one under the drug war.

According to the Human Rights Watch (HRW) report “Our Happy Family Is Gone”: Impact of the “War on Drugs,” children are left with physical, emotional, and economic issues, impairing the “normal” lives they once lived.

Read more about the HRW report by clicking the link above.

After Jomari, Aswang’s other central character is Brother Jun Santiago of the Redemptorist Brothers.

As Aswang chooses to eschew nameplates and character introductions, one could easily mistake Brother Jun – with his camera and ready-for-the-field attire – as part of the photojournalists he is often seen standing alongside. However, Brother Jun serves a higher purpose. As the head of social missions at Baclaran Church, he works not just to document deaths but help the families of the victims in the funerals and burials of their loved ones.

Patricia Evangelista writes about Baclaran Church’s sermon of dissent for Christmas 2016.

Filipinos celebrate Easter with crucifixion, flogging

In Aswang, Arumpac is fascinated by the Filipinos sense of tradition and spirituality. From the all-encompassing aswang metaphor to little superstitions, such as leaving a chick on top of a murder victim’s coffin. Highlighting this all the more is her choosing a protagonist that is also part of a religious order.

In one big scene in the film, Arumpac contemplates how blood begets forgiveness even in religion.

Explaining the PNP secret detention cell

One of the most harrowing scenes in Aswang is that of an anonymous woman who recalls how she was imprisoned in a secret cell behind a bookshelf in an unknown police station in Manila, where she was allegedly tortured and held for ransom by the precinct’s police.

As she sketches the inhumanely cramped design of her confines, we jump to actual footage of the Commission of Human Rights raiding to the undisclosed detention center and discovering 12 men and women being held in the tiny space behind a shelf. Just as the detainees thought they were being rescued, the police quickly processed the papers to legalize their holding at another precinct.

In this essay, Raymund E Narag, PhD, assistant professor at the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice of the Southern Illinois University Carbondale, tries to wrap his head around this shocking case of medieval-style detention.

The 7-part Murder in Manila series, published in October 2018, investigates the local chapter of a vigilante gang in Tondo, Manila, whose members had been arrested for murdering drug suspects and small-time criminals.

It won the Excellence in Human Rights Reporting Award and Excellence in Investigative Reporting Award of the Society of Publishers in Asia (SOPA) in May 2019. – Rappler.com

The streaming link to Aswang can be found on their website and their Facebook page. Those interested to know more about how they can help the families of victims can click this link.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.