SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Growing up, I devoured a lot of Hellboy, Stephen King, and horror anthologies on TV – Tales from the Crypt, Are You Afraid of the Dark, and Masters of Horror being my favorites.

Yet initiated to words like “weird fiction,” “cosmic horror,” or “Lovecraftian,” I was most fascinated with the stories that peeled back the curtain of reality, which showed a “secret history” of the world. And there was particular through line to the way these tales were told.

They conveyed dread as characters stumbled upon forbidden knowledge – the slow-mounting, unfathomability driving them to madness. And at the root of it all, insidious forces – primordial creatures older than time itself – and their worshippers, secretly the puppet masters of the universe.

H.P. Lovecraft was the progenitor of this kind of terror, so much so that his name has become an adjective for a whole sub-genre.

My fascination with the works he influenced led me to the man himself and to his own stories. (I still have a copy of the Necronomicon collection on my desk as I type this.)

Never meet your heroes

However, in an interview with Vanity Fair, novelist Victor LaValle described best how it was to discover Lovecraft, the man behind the prose, in your adulthood.

“It was like, say, your uncle or your aunt or your grandparent who you love dearly, but then you hit high school and start to realize that they actually say and hold a lot of really messed up prejudices.”

See, even for the early 1900s’ standards, Lovecraft was a fierce bigot who wrote hate speech, disguised as poems and essays, that expressed racist, misogynist, and xenophobic world views. One particularly disturbing piece is a poem about the creation of black men, where he likened them to beasts “filled with vice.”

More problematic is how some scholars, including author N.K. Jemisin, would argue that the aversion rooted in Lovecraftian horror most probably stemmed from Lovecraft’s own disgust for people outside of his race – the unknown existential threat in his stories an allegory for his own xenophobia.

Lovecraft’s body of work is an undeniable cultural touchstone. Not only did they influence contemporaries – the likes of Robert E. Howard (Conan the Barbarian), who also wrote for the cheap “pulp fiction” magazines Lovecraft’s works came out in – but they became inseparable from how we know sci-fi and horror today.

So, in this case, how does one separate the art from the artist?

These were probably the same questions that birthed HBO’s Lovecraft Country.

Unraveling Lovecraft

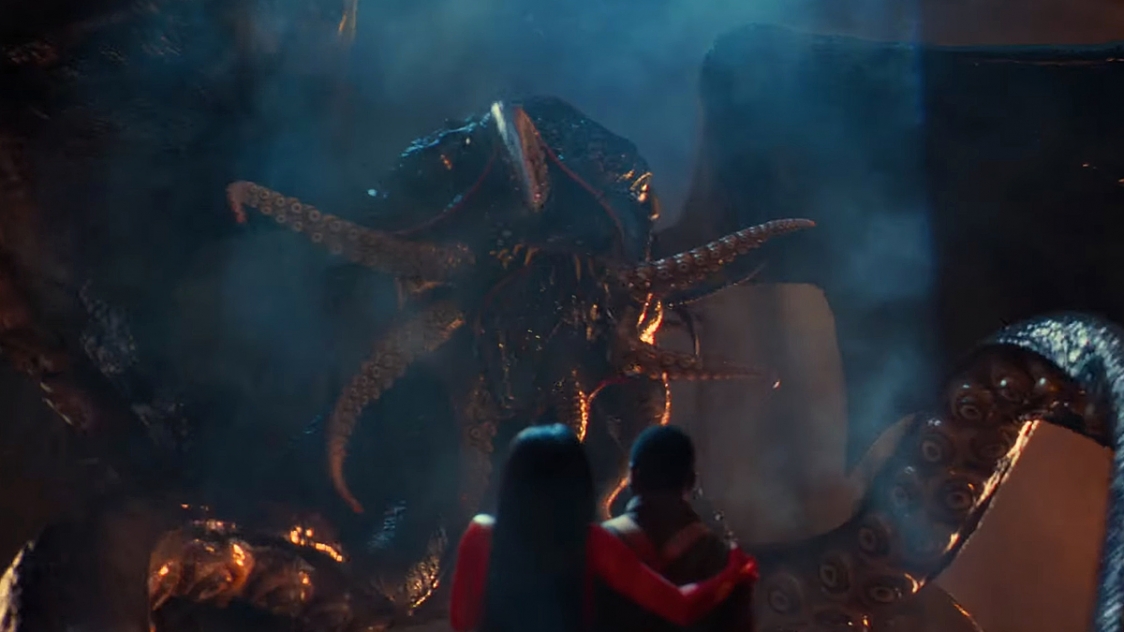

Adapted from Matt Ruff’s 2016 novel of the same name, Lovecraft Country follows Atticus “Tic” Freeman (Jonathan Majors), a Korean War veteran, as he embarks on a cross-country road trip across 1950s America in search of his missing father. Along the journey, he and his companions – his Uncle George (Courtney B. Vance) and childhood friend Letitia (Jurnee Smollett) – face a bevy of threats from shoggoths and wizards, to Klansmen, police, and White America, in general.

Oscillating between real-world monsters and tentacled beasts is a deft skill Lovecraft Country possesses. In its pilot episode, it doesn’t dive straight away into the supernatural. Instead, true to its “weird fiction” roots, it revels in slowly lifting the blindfold from our eyes. And this “unraveling” becomes the cornerstone of this show – intersecting plot, the genre writ large, and even the audience’s own experience.

In Lovecraft Country’s opening scene, Tic is established as a man with a weakness for pulp fiction. He is shown with a copy of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars – as he puts it, “I love that the heroes get to go on adventures in other worlds, defy insurmountable odds, defeat the monster, save the day” – and later Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness.

However, as if speaking for many BIPOC fans, Tic expresses inner conflict – guilt even – in enjoying these works. A Princess of Mars’ lead character, John Carter, was a white confederate soldier who fought for slavery. (“You don’t get to put an ‘ex-’ in front of that!” exclaimed one character.) Tic is also well-aware of Lovecraft’s unrepentant vitriolic racism.

Addressing this right off the bat strikes parallels between Tic’s journey and the audience’s. Tic knows that, at his time, the stories he loved, at best, rarely had space for people that looked like him. At the worst, they were derogatory to non-white folk. It is a confrontation for both Tic and viewers.

Tic is exposed to more realities as the show unfolds – from townsfolk that would love nothing more but to lynch him, to seeing how pain is a family heirloom, passed down through generations, for many black families. (And, oh yeah, of course, there’s also reveals of earlier races of men, “holy” lineages, and monstrous deities who see humanity as playthings.)

In a way that is both meta and ironic, everything feels “Lovecraftian” in the way dread is birthed from realizations about the nature of the world: Atticus’ acknowledging his books’ problematic histories; the repudiation of nostalgia and 50’s “American Dream” (which we should all know by now wasn’t inclusive); And us as viewers confronting our own feelings for an author and a genre he possibly birthed with hate at its core.

More than confrontation, a reclamation

However, more than just confronting these realities, Lovecraft Country is about reclaiming these toxic legacies and reappropriating them. Using them to empower the marginalized.

Lovecraft Country’s structure is looser than the heavily serialized shows of today and treats episodes as semi-standalone adventures. (While there is a larger arc at play, the episodes, beyond the first two, play out distinctly.) One is a haunted house story, another a homage to Indiana Jones. There’s also one that is more body horror.

Your mileage may vary with this “story-of-the-week” format, but it is clearly a deliberate choice. The original novel carried the same structure to mirror Lovecraft’s works – mainly composed of novellas, short stories, and poems.

Doing this, Lovecraft Country provides much-needed commentary on genre stories of the past, which could have benefited from non-white perspectives; and each episode in itself becomes a “one is to one” response, not just to the works of Lovecraft but to pulp fiction, overall.

Within the central plot, a black man seeks to control the powers used to subjugate him and his people. This in itself sends a message of taking back one’s narrative – not just within the show but also outside of it.

Beyond Atticus’s hetero-cis-male perspective, Lovecraft Country also seeks to correct some of pulp literature’s more problematic aspects by fleshing out its characters. Jurnee Smollett’s Leti takes center stage in the show’s third episode, making it clear that the show will not replicate the damsel-in-distress model pulp literature spearheaded. The inclusion of a Jamie Chung-centric episode down the line (episode 6) will hopefully also address the “yellow peril” stereotypes popularized by pulp characters such as Ming the Merciless and Fu Manchu.

Lovecraft Country seeks a solution to toxic legacies outside of the binary.

Rather than flat out reject Lovecraft and his influence or turn a blind eye and produce a “safe story” close to denying realities (here’s looking at you Green Book), it hijacks an entire genre.

While it may be too early to tell, if as a show itself, Lovecraft Country will be able to provide the same compelling, water cooler-worthy storytelling HBO has built a reputation out of, there are big takeaways from its intent.

With its existence comes the realization that, with some art, the connection artist and the work have become insoluble. In this case, Lovecraft’s work an inseparable influence on horror, fantasy, and sci-fi. However, as that same influence has trickled down, away and away from H.P. Lovecraft, I’d like to believe that so does ownership.

H.P. Lovecraft’s bigotry is transparent and a matter not really up for debate. Writers – not just Lovecraft Country’s – are grappling their love for his brand of fiction and the hate that unfortunately birthed it. Confronted with these realities, instead of being consumed by signature Lovecraftian madness, they take centuries-worth of anguish and say, “we can get madder.”

And somehow, we can rest easy at the thought that wherever H.P. Lovecraft lies right now, he’s probably rolling in it. – Rappler.com

The first episode of Lovecraft Country is free to stream on YouTube.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.