SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Spoilers for the entire season ahead.

There is a scene from Netflix’s new coming-of-age drama Heartstopper that has stayed with me since I watched it.

The two leads — Charlie and Nick — race through a crowded party in search of a quiet spot to talk. Beneath their ragged breath and laughter plays “Alaska” by Maggie Rogers — written in the throes of lostness, detailing how climbing a mountain granted its writer newfound clarity and peace. As they race upstairs, the music becomes the beat in every step (in one of the show’s many glorious needle drops):

And now, breathe deep, I’m inhaling

You and I, there’s air in between

Leave me be, I’m exhaling

You and I, there’s air in between

Just as they enter the room, the music fades out — transporting them away from the party and into a private world. Panting, they sit on the floor, the sudden silence making room for a truth neither of them have addressed. They inch closer together, their feet and hands touching ever so slightly, animated sparks flying at the point of contact. They share their first kiss and when they separate, it feels like the world has shifted back into its rightful place. When they kiss again, hands holding one another this time, one can’t help but root for this — whatever it is — to survive.

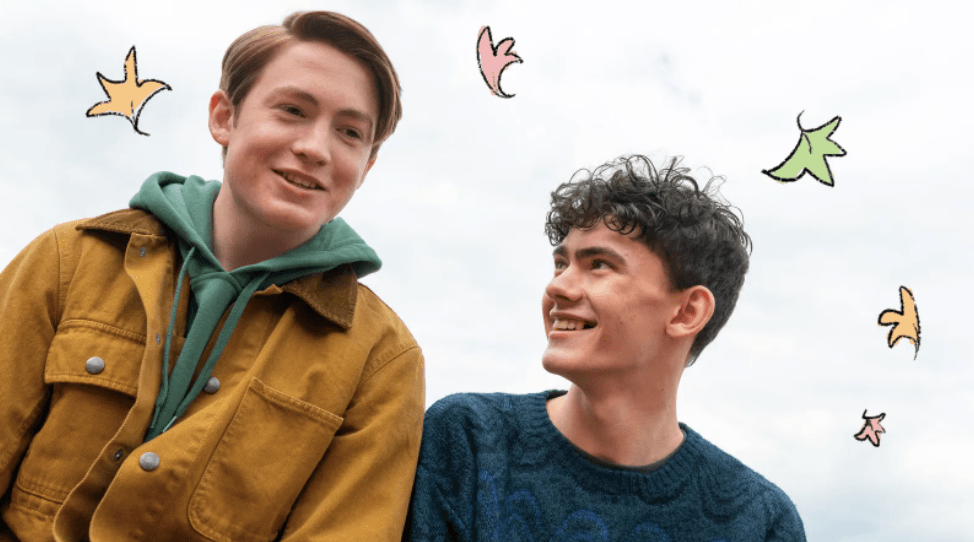

Adapted from the widely successful webcomic and graphic novel by Alice Oseman, Heartstopper is centered around the budding romance between the shy and apologetic drummer Charlie Spring (Joe Locke) and his new seatmate — the popular rugby player and golden retriever incarnate Nick Nelson (Kit Conner). Things change when the greetings become, in the words of critic Vincen Gregory Yu, “a crash course on 30 different flirty ways to say ‘hi,’” and both boys must figure out the boundaries not only of their ambiguous relationship but also of their identities.

It is easy to understand why people, particularly queer teens and even young adults, have been galvanized around Heartstopper. Writer Mia Brabham has noted the reemergence of “wholesome” media as the cultural centerpoint — with television shows like Abbott Elementary and Ted Lasso, and films like CODA garnering not only critical but also audience attention. Extending the observation, writer K-CI Williams observes that Heartstopper has remarkable parallels with Thai BL dramas, particularly Bad Buddy.

But even simply viewing the media landscape in the past few years, many successful coming-of-age stories such as HBO’s Euphoria lean towards realism and melodrama in the hopes of humanizing adolescence and depicting the disillusionment that accompanies growing up. While the misery can be comforting, the experience takes a mental toll and a sizable chunk of time away from its audiences, on top of possibly fetishizing the same teens whose stories it borrows. The cynicism and even the sex that is woven in the fabric of these modern teenage dramas is largely absent from Heartstopper.

In its place is a commitment to celebrating the mundane and the sincere, leaning into tropes and the story’s wholesome qualities. Framed like a pastel-colored dream with its subtext revealed to the audience through a mixtape, Heartstopper plays out more like speculative fiction — especially as animations enter the scene, confirming feelings, fears, and fantasies that exist within our characters’ heads. Yet unlike its predecessors, it doesn’t draw out lies about gender and sexuality for the sake of drama. Nor does it need to complicate its simple story (a failing of the narratively similar Geography Club).

Instead, Heartstopper attempts to create a queer utopia by repurposing common images from heterosexual romance films — kissing in the rain, holding hands in the theater, taking pictures in a photo booth, throwing longing stares from across the room. The teens within the show are aware of their participation, their yearning for this larger myth in romantic love, and in giving into its cheesiness, it unearths how magical these moments are and can be when you’re discovering them for the first time. The series trusts that the audience knows the formula and plays with the impending dread and awkwardness they’ve come to expect from LGBTQ+-centered narratives, but it doesn’t give into the fatalism, even if it’s at the expense of believability.

For example: In the fifth episode titled “Friend,” we expect Nick to ditch Charlie’s birthday for his accidental date with the abrasive “ally” Imogen (Rhea Norwood) to maintain his “straight” facade (whatever that means). There is an iteration of this in nearly every queer romance, even in the pop opera Bare. But Nick refuses to be cruel to Charlie, Imogen, or himself in maintaining this false identity thrust upon him, and decides to come clean to Charlie and Imogen instead. The surprise comes not from the decision but from how its characters respond to the situation — with more maturity and understanding than even I personally thought teenagers were capable of.

It helps that the young British cast have not only chemistry but also the charisma to pull off what they’re doing. In Nick and Charlie’s immediate orbit are friends who are also members of the LGBTQ+ community, who also navigate their own labyrinths within their respective British secondary schools. Elle (Yasmin Finney), a young black trans woman, initially struggles to find friendship after moving to an all-girls school. She eventually meets the couple Tara (Corinna Brown) and Darcy (Kizzy Edgell), who have just recently publicized their relationship and are dealing with the aftermath. Meanwhile, Tao Xu (William Gao) finds difficulty holding onto his friendships with Charlie and Elle amidst all the changes happening to them.

But as Lynne Joyrich has pointed out in “Queer Television Studies: Currents, Flows, and (Main)streams,” the entrance of any queer story into a mainstream medium such as television will obviously have its paradoxes. One cannot help but point out that Heartstopper still operates within the heteronormative frameworks and binaries that queering itself tries to challenge — the divisions between girls and boys; the pressure on the closeted to become out individuals; the dichotomies in the roles expected in a relationship; even the adherence to a heteronormative gender presentation. Added to this are the sanitization of the dialogue for television — most noticeable in the absence of curse words from an all-boys’ school, even when they’re generously used in the graphic novels and webtoons.

Still, Heartstopper is aware that its school isn’t perfect: there is discrimination and bullying and things get bad. It addresses just how bad this can get within its first episode — as Charlie escapes to the art room and talks to Mr. Ajayi (Fisayo Akinade), unraveling his year of being shamed for being gay. But it doesn’t depict high school purely as hell — there are pockets of salvation and people who safeguard those spaces. The utopia created by the show isn’t so easily shattered by negative forces, and the consequences of queerness aren’t as extreme.

The product is a show that imagines a different kind of coming-of-age — one wherein teenagers are not beholden to their traumas or peer pressures; wherein miscommunications are addressed before they snowball into something too large to handle; wherein transparency and accountability is a first response rather than a last resort; wherein complex questions can have simple and honest solutions; wherein decisions are guided not by fears but by hopes.

I wish shows like this existed when I too was 15 years old. But I am glad that they exist for this new generation. Queer lives in high school used to be obsessed with languishing in a past that can no longer be recovered or a future that has yet to arrive. But Heartstopper presents us with a queer story that is anchored in the present, no matter how it may hurt, as long as it is spent with the ones you love. – Rappler.com

Heartstopper is available on Netflix.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.