SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Spoilers ahead.

The first thing that arrests me in UP Dulaang Laboratoryo’s latest staging Nawawalang Gabi, Ninakaw na Araw is its sheer brazenness, especially for someone coming to the show without any idea what to expect and only armed by curiosity. After all, art criticism, to an extent, means allowing oneself to be taken by surprise, to try the untried and to test the untested, in an attempt to yield something meaningful, something that demands interrogation.

Collaborating with director Banaue Miclat and dramaturg Brian Arda, playwright Joshua Lim So uproots his Palanca-award winning script Araw-Araw, Gabi-Gabi to tear open wounds, however hard and deep, that have yet to heal amidst the Philippines’ impaired historical memory and callous disregard for human rights.

At the center of the play are two activists, one well into his 40s (Janno Castillo) and another in his early 20s (Johnny Maglinao), whose lives are upended after being captured by paramilitary forces based on unfounded allegations. Weak, hungry, and almost delirious, they are forced to confront their tortured state and think of ways to pull themselves out of a cell so wretched, windowless, and sustained only by a single light bulb that it may well be built underground, considering the state’s obsession with surveillance and secrecy.

The decision to adapt this particular story for the stage cannot be more pressing, as we find ourselves at the behest of another Marcos, after more than three decades of enduring the dictator’s rule — a regime that has since produced an estimated 2,300 cases of enforced disappearances, based on latest data from the Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearance. In fact, earlier this month, new names were added to this list, as two Cordillera-based indigenous peoples’ rights activists — Gene Roz Jamil “Bazoo” de Jesus and Dexter Capuyan — had gone missing, all while progressive groups are relentlessly red-tagged by state officials, if not by other equally dangerous reactionary forces.

And the play situates us right into this fraught zeitgeist. It begins with absolute darkness, rendering the entire room in pitch black, as though inviting the audience not only to feel but also ruminate over this insistence of violence, amidst the macabre sounds in the background. Then, lo and behold, the precision of suffering. “Ang pagdurusa, siya ang panginoon,” says one of the characters.

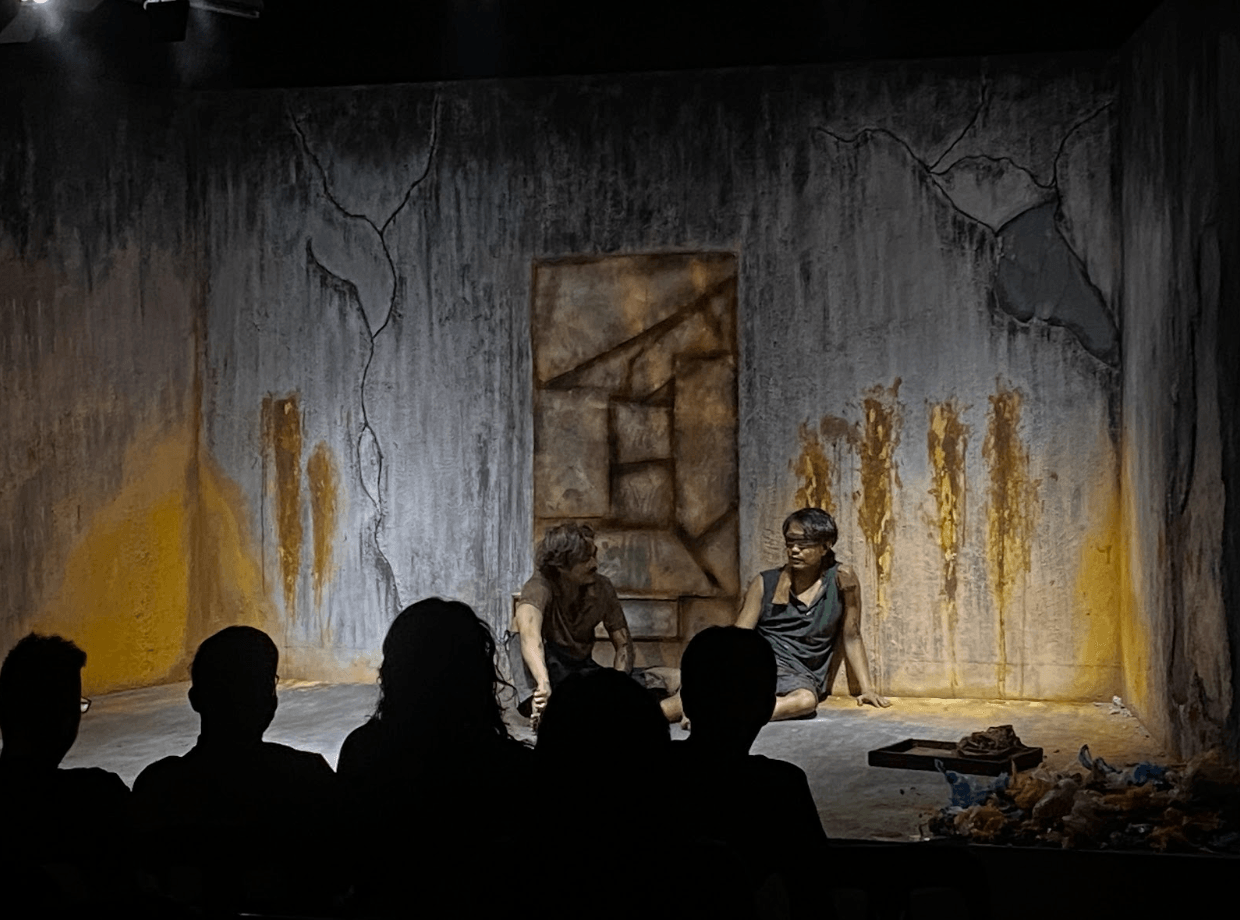

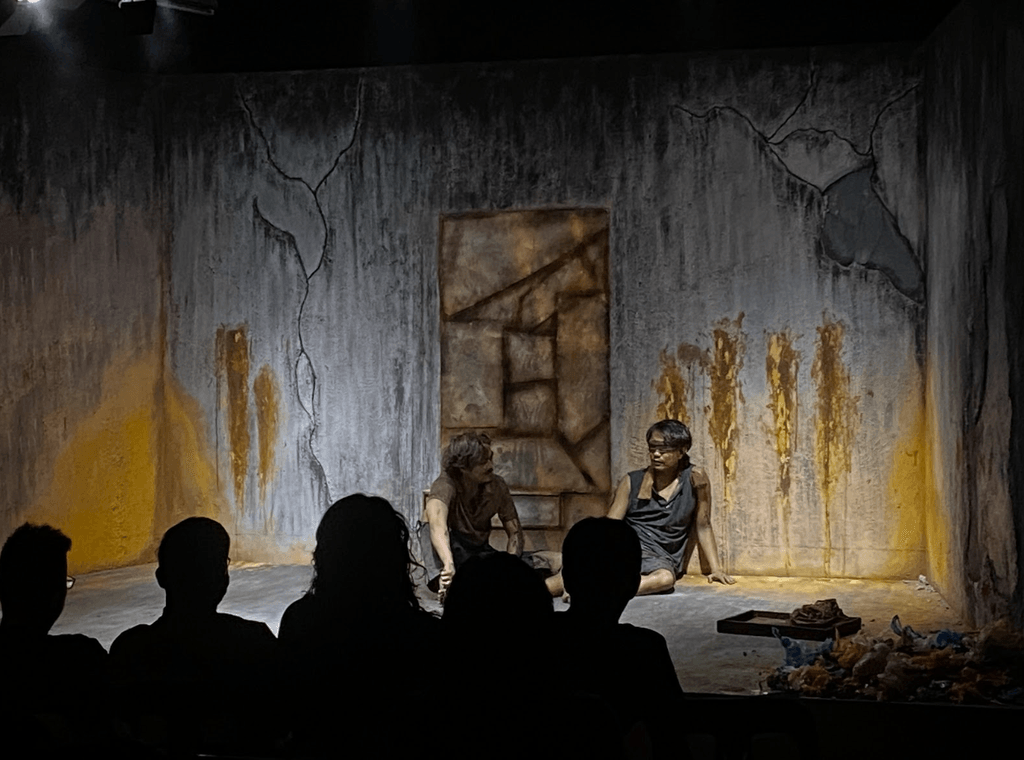

We see two bodies and two souls perpetually tormented in a space that is almost the embodiment of Plato’s cave in his principal thought experiment. Production designer Cris Ramon captures, in exacting simplicity, the verisimilitude of a state prison reserved only for revolutionaries, rights advocates, or ordinary citizens who dare to show even the slightest form of resistance, making the story more lived-in. Walls, filled with dirt and blood, look as filthy as a dumpsite or an abandoned warehouse; rubbish is littered across the floor. It’s as if one can smell the putridity the space intends to emit. The actors, appearing all greasy and foul-smelling, complement this mood.

While the story at times feels loaded, one cannot help but admire the trust that Miclat and So put in their two-man cast, emboldening them with the liberty to experiment and take their characters to interesting zones. Castillo and Maglinao’s dynamic commands the narrative’s emotional heft — two people, one pragmatic and the other self-righteous and ideal, desperately trying to keep each other afloat; two people whose fates roll on a cruel Möbius strip, forever searching for a cardinal point, a way back to their normal lives.

Had there been a casting mistake, the adaptation would have found itself at a crushing standstill, precisely because Castillo and Maglinao turn in searing and expansive work that sees their characters descend into madness, counting their days, both numbered and not, until they run out of fingers to count them with, humoring their struggle with games and endless introspection. And when the pangs of pain gnaw at them, they remedy it with numbness. “Walang mata, walang tainga, walang katawan, walang isip, walang hangin, walang sakit, nirvana,” they say.

Corollary to this is how state forces slowly yet gradually mutilate their bodies — an act so vile that even the monsters themselves can only commit it in the shadows, aware that the corruption of the body is also the corruption of the soul. Acts of desecration, a blatant violation of international humanitarian laws, have long been part and parcel of the national military’s senseless witch-hunting of progressives and revolutionaries, bent on parading every fallen body as a trophy of war.

Nawawalang Gabi, Ninakaw na Araw may not be the kind of staging that is heavy on musical numbers or production spectacle, especially when contrasted with works with much deeper pockets that have graced Philippine theater this year, but it recognizes the function of art enough to be disruptive and move the conversation forward during this politically heightened time. What it manages to highlight, at its core, are the lengths our oppressors are willing to take to stifle dissent, to maim our right to safeguard ourselves from injustice and abuse, so much so that we become acclimated, if not complicit, to erasure and impunity. It tells us how the struggle for radical liberation can never be obtained from a place of comfort.

Towards the end, the young activist declares: “Kinain na ng lugar na ito ang lahat ng akin. Ang lahat-lahat.” So it begins to hit you why the staging culminates the way it does. It’s not because Miclat and So lack the imagination to create a way out for their characters, but because they invite that of us to look at the nameless faces that the people in power have long been burying to the ground. We stare at the two bodies, now in Pietà position, until one of them runs out of breath — an image rendered more brutal and arresting by the drama of the spotlight, dying ever so gently, like a nation that rages against insidious forces, in spite of everything. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.