SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

When I first watched The Reconciliation Dinner in December 2022, Ka Leody, one of the presidential candidates in the 2022 national elections, was seated five rows in front of me. Though Luke Espiritu and Risa Hontiveros were also in the room, I found myself unconsciously checking Leody’s reactions throughout the one-act play, wondering if any of this, for a politician and grassroots political organizer such as he, was any funny. Written by Floy Quintos and directed by Dexter Santos, The Reconciliation Dinner seems like it’s extracted from the wellspring of our country’s collective memory.

It begins with an attempt at empathy. During one of their regular dinners, Dina Medina (Stella Cañete-Mendoza) notices that her long-time bestfriend Susan Valderama (Frances Makil-Ignacio) is quiet. When she asks what happened, Susan confesses that she and her husband Fred (Jojo Cayabyab) are upset over Duterte’s decision to bury Ferdinand Marcos Sr. in the Libingan ng mga Bayani. Instead of extending empathy, Dina and her husband Bert (Randy Medel Villarama) dismiss the event as a non-issue. Heated words are exchanged. Lines are drawn. The atmosphere is ruined. Dina, hoping to salvage the evening despite this political divide, makes a plea: to put aside their political differences and share a peaceful meal. Everyone agrees.

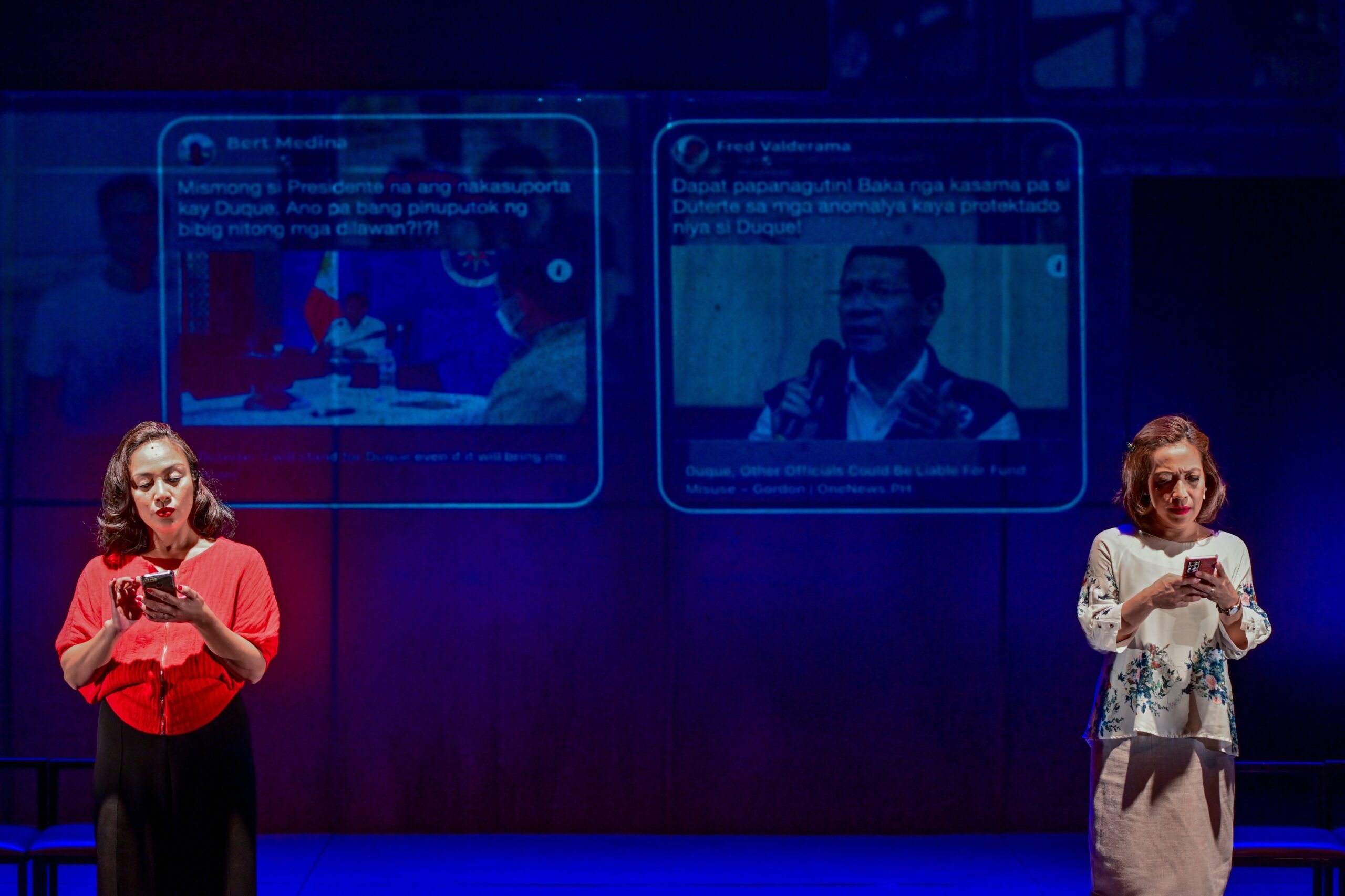

But what seemed like a sprain was actually a fracture. Across seven years, wounds meant to heal instead festered, eating away at their principles, creating a chasm between best friends. A pandemic and a presidential election drives another wedge into this relationship and ideological battles transfer out of the dining room and into the online space. Facebook status updates become passive-aggressive weapons wielded against one another until petty acts begin having real-life consequences. The political geography appears to the audience as screencaps from social media projected onto the minimalist set, a combination of the work of video designer Steven Tansiongco, associate video designer Ces Valera, production designer Mitoy Sta. Ana, and dramaturgs Marvin Olaes and Davidson Oliveros.

Proximity is the currency of The Reconciliation Dinner. With The Kundiman Party in 2018, Quintos solidified himself as one of the country’s sharpest observers of how social media infiltrates the home, programs us to falsely conflate public opinion and real-life political action, and forces us to wrestle with how difficult it is to live morally in a country filled with corruption. Horrid politicians, which function as the invisible forces in the play, benefit from the polarizations and in-fighting because it paralyzes citizens into inaction. Quintos renders this sociopolitical stasis so tangibly in The Reconciliation Dinner by separating the monologues, allowing us access into the minds censored by pleasantries and social filters, thoughts isolated through the lighting design of John Batalla.

But what reunites the two families is not respect or understanding, but guilt. Dina’s breast cancer recurs. She calls Susan out of desperation. The threat of a mastectomy forces them to be vulnerable with each other, to relinquish their moral high grounds, to start listening not to each other’s words but hearts. Tears come. Promises are made. A reconciliation is easier when death is at the door.

When one looks at Quintos’ larger body of work, one finds these religious themes embedded deep within them. Through this lens, The Reconciliation Dinner also becomes a tale of modern idolatry — how reverence of an idea, a country, a politician, maybe even a friend, become poisonous in large doses. Facades of perfection shatter when expectations aren’t met. The text becomes a funhouse mirror for the audience to see themselves reflected in, forcing them to face questions they’ve been evading: In the face of damning evidence, is absolution possible? What happens to people when certainty is replaced by mystery? Will they believe in miracles or cling to lies?

The answer, it seems, is chaos. To this end, Quintos is successful at capturing how post-election resentment crystalizes into blinding rage and self-righteousness. A new monologue delivered by Makil-Ignacio finds her character reciting an aria of unbridled anger. Susan’s sadness at Robredo’s loss grows too large for her to handle, transmogrifying into monstrous resentment that only the audience can hold. Compassion takes a backseat. Her body loses poise! She flails! She begins pointing fingers at her imaginary workers! The gesture is comical to the elite yet disturbing to blue-collared workers. Her finger draws a line between her and her subordinates, one she crosses momentarily through her imagination. She returns only after realizing that it is not what Robredo would have wanted, speaking of the presidential candidate like Mama Mary.

It is a monologue that purposely stops short of insight. Data, political theory, rationality, hell even common sense, do not matter as much when we are in pain. The only reality one sees is that goodness and honesty cannot seem to win. But until when can we hold onto such grudges without being weighed down by them?

These additions make The Reconciliation Dinner more entertaining, with Phi Palmos’s Norby standing out, his every line dropped like a comedic bomb – a deadly mixture of truth, ease, and sarcasm. But other aspects of the work feel as though they’ve been lost integral parts, as the characters become more simplistic and childish. Of the Medinas, Cañete-Mendoza’s Dina is the most magnetic because of her benevolence, her character’s public relations background shining through despite only being mentioned twice. Dina never intends to be mean unlike her daughter Mica (Harriete Mozelle in the first run, Mica Pineda in this run) nor does her condescension masquerade under humor like Bert. Such villainy — in both performance and writing — renders the two other members of her family less arresting. The dissonance between her putrid politics and her kind behavior makes it difficult to break off the friendship with her, especially because she hasn’t done anything unforgivable. By showing how Dina grows impatient with Susan in the second run, the power of Cañete-Mendoza’s performance loses some of the contrast that made her the most interesting actor onstage.

Maybe this is the point. Maybe by depicting how such infuriating political conditions infantilizes even the best of us, it leads us to confront our own foolishness and simplicity, satirizing our regression in a world experimented on by Cambridge Analytica. But by focusing on the solispsism that everyone has succumbed to, The Reconciliation Dinner concerns itself only with the dominant narratives of our time. Quintos and Santos strain to break away from the binaries they claim to critique, finding themselves instead trapped in the language of labels and the cycle of national contempt. How can you mend the political divide if only one side of the party attends?

The play arrives at several points where it can offer an escape from the narrative of Robredo versus Marcos Jr. When Ely (Nelsito Gomez), Mica’s husband, reveals he voted for another candidate, there is an opportunity to introduce a wildcard, a political ideology that counters the two. But more poignantly, when Fred asks if anyone is happy about the state of the nation and is only greeted by silence, there is an opportunity for the discussion to break away from the binary. Instead, things return to what once was, the sentiment of progress quickly pushed aside because human nature makes blame easier than accountability. Associating oneself with a historical struggle makes us feel validated, but also has the potential to ruin us, and this myopia is what cages the Filipino people and the play itself.

To praise The Reconciliation Dinner for “not offering easy solutions” and to rest on the comfort it provides is to misread the work. Quintos does, in fact, offer three distinct paths to moving forward while also laying out their consequences. The first is to leave and to avoid the political repercussions that break the spirit of the middle class, but to be viewed as traitors of the national struggle. The second is to stay and continue to fight the oppressive structures that benefit the powerful few without certainty of winning or financial return. The third is to remain apolitical, in denial, and insulated by privilege, while blatantly benefiting from systems in silence, even if it’s at the price of loneliness.

To end with Dina crying, alone, her cancer ruining her insides without us seeing, would have been enough of a metaphor for our sociopolitical climate. Even the rest of the world’s. But Quintos and Santos refuse to end with this image of absolute despair. Instead, Bert appears, wiping his hands and face, rationalizing his earlier violent break as a joke. Dina, seemingly fed up, surprises herself by slapping him, then lunging into his arms for solace. The image intends to impart hope and humor, but shows an implicit cycle of abuse, one that alternates between social reward and punishment in an effort to control their behavior. Was this where it was headed all along?

As the play ends and the audience stands and applauds, a memory of the first run jumps forward in my mind. Mica and Bert are listing the presidential candidates to make shallow cases against them: Pacquiao, Moreno, Lacson, Robredo. By process of elimination, the Medinas settle for Marcos, though they make no case for why he should win. I notice something: there is no sixth name. I remember Leody is in the crowd. I wonder how he feels. I crane my neck for a chance to look at him. I see his arms are crossed. Other heads turn towards him too. I cannot see his reaction.

In this absence, I find my answers. – Rappler.com

‘The Reconciliation Dinner’ ran from May 20-21, 27-28 at 3 pm and 8 pm at the Power Mac Center Spotlight at Circuit Makati.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.