SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Spoilers ahead.

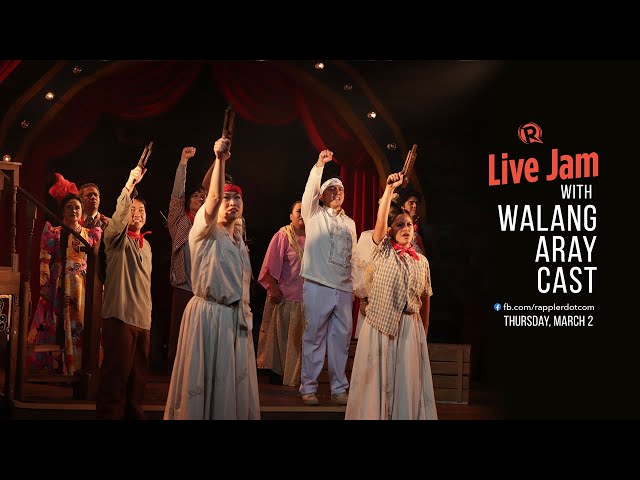

The opening number of Walang Aray prepares us for the self-reflexiveness and tongue-in-cheekness of the musical. Cleverly titled “Front Act,” a trio of performers distract the audience while everyone backstage searches for the sarswela’s star Julia (Marynor Madamesila). Julia has everything — charisma, uniqueness, nerve, and talent, and a secret boyfriend Tenyong (Gio Gahol) who is more than happy to support her from the shadows. Never mind that her mother Juana (Neomi Gonzales) is trying to set her up with someone else; Julia and Tenyong’s love is the stuff of Taylor Swift songs.

But amidst political turmoil, relationships don’t always survive. When Tenyong’s parents unexpectedly die at the hands of oppressive church officials, he joins the revolution, recognizing that his love for Julia is sustained by his love of country. It’s a classic will-they-won’t-they narrative that leans heavy on romance and comedy, the plight for independence doubling as an unfortunate backdrop and source of conflict.

Walang Aray was adapted by Rody Vera from Severino Reyes’ Walang Sugat — a widely-revered sarswela set in 1896, published in 1898, and staged in 1902 as a way to assert Filipino patriotism under the Spanish Occupation and early American rule. Hoping to reintroduce the sarswela and Reyes’ work to unfamiliar audiences, the Philippine Eductional Theater Association (PETA) chose to stage Walang Aray as its post-pandemic comeback, modernizing the source text by infusing the work not only with snippets from current events but also an array of pop culture references and isms specific to the Filipino milieu — from Maria Clara at Ibarra and impressions of Rufa Mae Quinto to digs at the MMDA and Sara Duterte’s mandarin speech. Vera describes the new musical as “a spoof and a tribute” not only to the sarswela but also contemporary theater in the Philippines.

High level of execution

Beneath this treatment, Walang Aray is fascinating as a coming-into-identity after loss, specifically through art. When Julia sings a seemingly Shakespeare-inspired ballad in Act I (“Huwag Mo Akong Sasaktan”), she hasn’t fully understood the pain of what she’s performing. When art becomes a respite in Tenyong’s absence and her own powerlessness in Act II, she sings with specificity (“Magbalik Ka Na Mahal (Kay Ginaw Ginaw”), her maturity and vulnerability even embarrassing her. Even if the lyrics speak of longing for Tenyong, they double as a portrait of a nation whose fractured existence at the hands of the colonial forces push loved ones into distance.

Littered throughout Vera’s intelligently written book and lyrics and Vince Lim’s music are these nuances. Comedic flirtations between Tenyong and Julia (“Pangako Yan” and “Ma”) give way to reflection in solitude (“Hintayan” and “Ako’y Ibong Sawi”), while questions of male desirability and masculinity are presented through cute and catchy tunes (“Tipo Kong Lalaki” and “Luv U 4Ever”), even raunchy ones (“Chicks” and “Borta”). Lim manages to blend humorous storytelling and Pinoy pop perfection to create songs that, borrowing words from Jessica Zafra, “contain all the thrill of first love and the agony of heartbreak.”

While the comedy at times feels overloaded and detracts from the truth and pace of the story, one can’t help but feel at awe of the freedom director Ian Segarra emboldens his cast with. The entire ensemble is playful and giddy with their experimentations, especially Neomi Gonzales, and the duo Kiki Baento and Carlon Josol Motabato, who stand out as the trio that hover around Julia, their mix of deadpan delivery and physical comedy becoming a reliable punch to the story. But it is Marynor Madamesila and Gio Gahol who are perfect in their roles as Julia and Tenyong, respectively. The two blend sincerity, chemistry, and impeccable comic timing, turning plain words for amateurs into comedy gold, and together their wonderful weirdness comes off as the shared language of lovers.

Rationalizing product integrations

The distinct accomplishment of Walang Aray is how it executes its absurd product integrations. Anachronistic references to Dunkin Donuts, Starwax Floor Wax, PHINMA scholarships, and Sun Life Insurance take advantage of the farcical nature of the musical and become unexpected yet effective punchlines. These highlight the possibility of mixing commerce and political theater, while also becoming a worrying sign of what is required to sustain original work in current times.

But the production’s biggest product integration is in casting the young love team KD Estrada and Alexa Ilacad (known together as KDLex) as one set of its leads. On a metatextual level, it’s easy to understand this decision. Walang Aray’s central pairing can be seen as a love team themselves, and KDLex draws in the younger audience that PETA hopes to reintroduce the sarswela to. But beyond this, the popularity of the sarswela from the 1900s to the 1930s intersects with the rise of the first recorded onscreen love team — Gregorio Fernandez and Mary Walter — in the 1920s. At the hands of KDLex, Walang Aray becomes a depiction of how entertainment and romance are routinely used as distraction during difficult times.

Issues with gender dynamics

But their integration also has implications in how the production is read, particularly through the lens of gender. Historically, love teams have been used to promote heteronormative ideas of love, identity, and romance, and in Walang Aray, Julia and Tenyong clash with opposing structural, colonial, and romantic forces that are mostly either queer or queer-coded. Performed with flamboyance, Padre Alfaro (the ever-reliable Johnnie Moran) is presented as a raging hypersexual and possible closet case, his inward repression externalized as a force of structural oppression. Meanwhile, the ilustrado Miguel (the convincing womanizer Bene Manaois) is acutely aware of his desirability but treats marriage more as a contractual obligation, another rule to be upheld and followed.

The marriage between Julia and Tenyong — two characters who, when portrayed by Ilacad and Estrada, seemingly embody chastity and naiveté — becomes a way of warding off these queer colonial powers. Padre Alfaro has a tantrum of betrayal, indicative of his self-centeredness and regressive politics, while Miguel admits to his homosexuality and even acts upon it when a hypermasculine rebel rips his shirt off. While the characters themselves are more archetypal than complex, their narrative weight invites scrutiny over how PETA explores gender and power in their original work, especially because many of the antagonists in PETA’s repertoire have either been queer or queer-coded.

Underrated direction

It’s easy to critique the thinness of Walang Aray, especially when contrasted with PETA’s previous works that more overtly wrangle issues of queerness and immigration (Caredivas), imperialism, entertainment and gentrification (Rak of Aegis), and even the ouroboros-like nature of history and authoritarianism (3 Stars and a Sun and Game of Trolls).

But what remains underdiscussed is how Segarra mines Vera’s text to depict the politics of class and art in 20th century Philippines. The invisible lines between the working class and the upper echelons are felt through the ways characters are spatially segregated: fans are restricted from access to stars, letters between lovers are delivered by househelp despite the dangers, and oppressors are often either physically elevated or ever-present in the background. Only Tenyong and Julia are able to oscillate between, maybe even challenge, these unspoken boundaries.

That is, until the final scene, which Vera and Segarra stage in a cockfighting arena. In anthropologist Clifford Geertz’s seminal work Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight, he writes that the sabungan is a place that enabled status relations in Balinese society, and in a similar manner, Vera and Segarra transform the sabungan from a space associated with modern violence, greed, and unequal power dynamics into a site of love, resistance, and justice.

These meanings can easily be lost to audience members (such as myself) until actively sought out. But it’s fascinating to know that these seemingly innocuous choices, these negligible one-off jokes, have immense power to them once a reader is curious enough to look and analyze. It’s clear that Walang Aray does not underestimate its audience members. And isn’t that what great art should do — invite its readers to not only feel, but to be curious too? – Rappler.com

Walang Aray runs again from October 6 to 22, 2023 at the PETA-Phinma Center, Quezon City. For tickets, check out Ticketworld.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.