SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

On the eve of November 11, 2020, Seraphina Ramos* was caught off guard by heavy, continuous rain brought by Typhoon Ulysses (Vamco). The typhoon affected not just her one-story shanty house, but also the palay stock she bought as an investment to survive life away from the Taliptip coastal in Bulakan, Bulacan.

It’s been more than 10 months since Ramos left Sitio Dapdap in Taliptip and relocated to one of Bulacan’s landlocked towns. Typhoons like Ulysses remind her of her former home, where intense flooding was unheard of in the close to 3 decades she had lived there.

But things could be different now that the environmentally high-risk San Miguel Aerocity project is set to be built.

A quick search using HazardHunterPH showed that Taliptip in Bulakan is prone to ground shaking, tsunami, and storm surges. It’s also highly susceptible to liquefaction and flooding. HazardHunterPH is an online tool powered by government-led GeoRisk Philippines to assess and inform the public about geohazards in a specific area.

The assessment said that ground shaking can occur in the event of an earthquake. With strong ground shaking, liquefaction – the loosening or quicksand-like behavior of land especially near rivers, lakes, and coastal – can follow, causing deaths and damage to infrastructure.

Bulacan is vulnerable to these natural hazards, as it is situated along the West Valley Fault System, an earthquake generator capable of producing a magnitude 7.2 earthquake, according to the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. Based on historical data, experts have said that the fault is ripe for movement.

According to various studies, Bulacan also experiences rapid land subsidence or the sinking of land due to excessive groundwater extraction. Subsidence and rising sea levels because of the global climate crisis leave Bulacan communities vulnerable to severe flooding.

Narod Eco, a geoscientist and researcher at the Marine Science Institute of the University of the Philippines (UP), warned in a forum in June 2020 that Manila Bay reclamations such as the planned construction of San Miguel Corporation’s (SMC’s) New Manila International Airport (NMIA) will only aggravate these multi-hazard conditions, inevitably putting people in harm’s way.

He added that the risk of storm surges – a tsunami-like seawater rise associated with typhoons – is higher in the bay due to the shape of its seafloor. The NMIA project site, located in northern Manila Bay, can potentially have 3- to 4-meter high storm surges, based on a 2014 study by Project NOAH or the Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards.

NOAH was a government-initiated effort in 2012 that aimed to be the Philippines’ primary disaster risk reduction and management program. After being defunded by the government in 2017, it is now managed by UP and housed at the UP National Institute of Geological Sciences (NIGS).

In recent years, scientists and organizations worldwide have started embracing a critical approach in addressing disaster issues, highlighting the role of human involvement in shaping peoples’ vulnerabilities to natural hazards.

“Disasters happen because of the presence of people or human activity, so it’s not really natural. When there’s a disaster, it means that the society has shortcomings in its societal governance, among others, or infrastructure. There’s an institution or person who should be made accountable for why there are deaths or destruction,” Eco, who also previously worked in Project NOAH, said in a mix of English and Filipino.

Beyond the geological processes, he proposed that disaster studies should understand the history and motivations of people making up a community such as the state of the relocation area, quality of houses, and current living conditions that contribute to the people’s ability to cope with possible future calamities.

Having closely collaborated with UP science workers and Taliptip fisherfolk in understanding the environmental effects posed by the construction of the Bulacan aerotropolis, Eco related this with the recent displacement of former residents, saying, it bears disaster risks.

One with nature

An August 2019 geohazards study by the UP NIGS which focused on the aerotropolis project area showed that Sitios Pariahan, Kinse, Dapdap, and Camansi are sea frontiers, making these communities more vulnerable to natural hazards.

But the study also noted that Taliptip residents have withstood earthquakes, floods, and storm surges of varying intensities for more than 60 years of living in the bay through an effective local early warning system, practical preparations, timely evacuation, and resilient rebuilding of homes. No casualties or major injuries have been recorded to date.

Former residents told Rappler that they had learned to manage the disaster risks, always returning and rebuilding their houses after because of the livelihood and the benefits of residing in the Taliptip coastal.

Ramos said some would even choose not to evacuate because the rainy season brings another source of income: washed-out items floating by the bay that residents could collect and sell as recyclables.

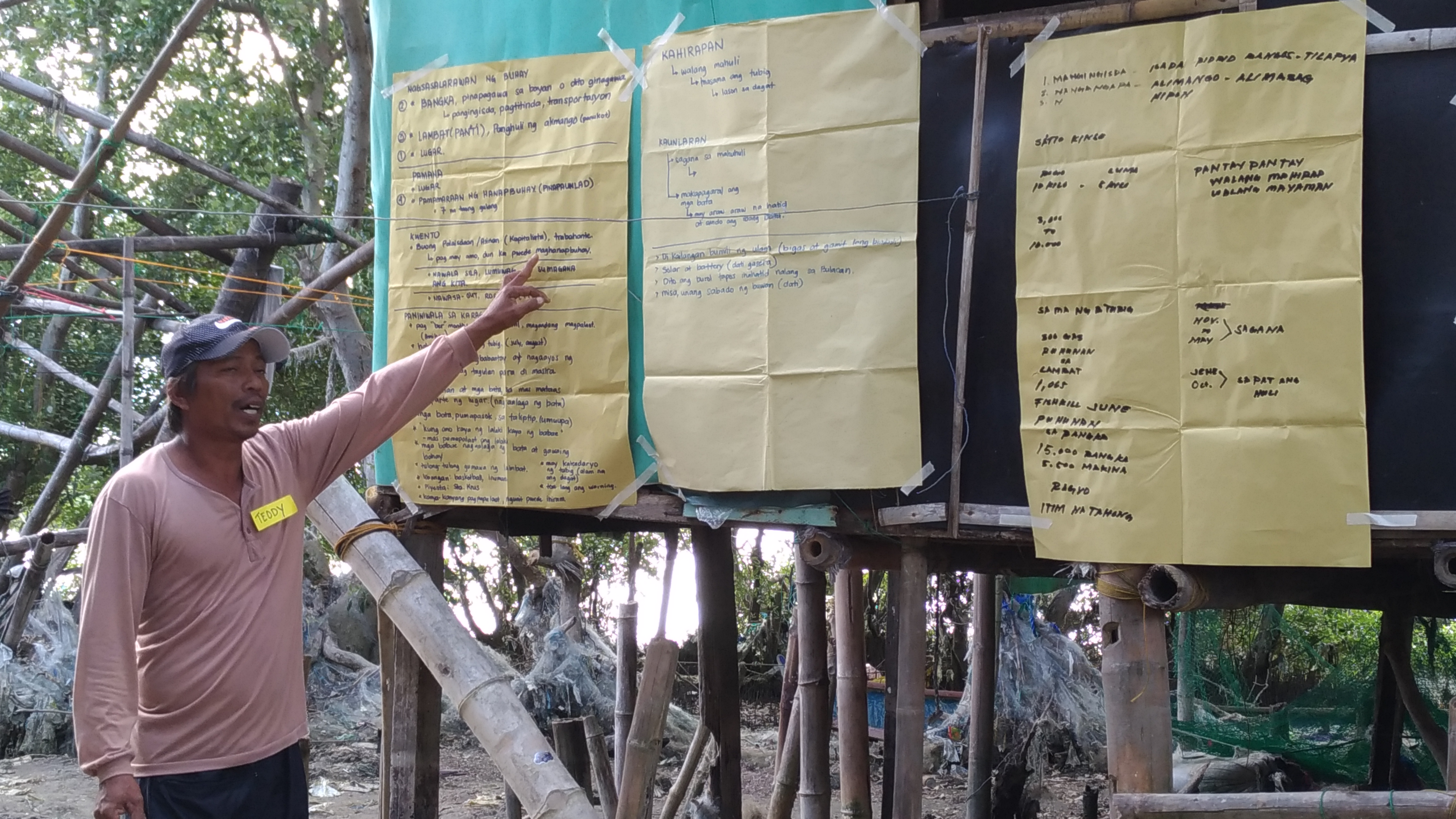

The Taliptip communities valued and constantly adapted to the changes in their environment as these were intertwined with their livelihood and culture as a people, explained Warner Carag, project coordinator and member of Advocates of Science and Technology for the People (Agham).

Given these assessments, the report said that geohazard issues cannot be used as justification for the relocation of the coastal sitio residents. The study recommended that SMC find an alternative site and reduce the airport project scale because large infrastructure isn’t suitable and poses many safety issues for communities.

The geohazards investigation in Bulacan started as part of an extension project funded by UP Diliman’s Office for the Vice Chancellor for Research and Development through the linkaging efforts of the Bulacan Ecumenical Forum (BEF), one of the groups that make up Akap Ka or the Alyansa para sa Pagtatanggol ng Kabuhayan, Paninirahan at Kalikasan sa Manila Bay.

This extension work evolved to become part of a counter environmental impact assessment (EIA) conducted and developed with the Taliptip and Obando fisherfolk from 2018 to 2019. It discusses the environmental, socio-economic, political, social, and cultural impacts of the aerotropolis project on the affected coastal communities.

Saving the mangroves

In May 2018, Taliptip fisherfolk reported illegal and massive mangrove cutting within their sitios. Three months later, residents had to deal with the immediate consequences of the loss of mangroves, said Fr Ambet dela Cruz of the BEF, a group of concerned clergy that pushed for stakeholder dialogues and engaged with Taliptip residents starting 2017.

He recounted stories from Sitio Bunutan residents about flood waters as high as one meter entering their community for the first time. It took two weeks for the flood to subside.

In the same month, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Central Luzon bureau called for a multi-stakeholder dialogue and a technical conference in an attempt to resolve the issue.

According to reports by the Community Environment and Natural Resources Office (CENRO) in Guiguinto, Bulacan, 653 mangroves were cut down and left behind in 4 sitios affected by the airport project. The office also noted that according to Epifania Samonte, Taliptip barangay secretary, the cutting of mangrove species by the developer of the proposed airport site – involving SMC’s subcontractor Silvertides Holdings Corporation (SHC) – began in May 2018. Residents tried to apprehend the illegal cutters, to no avail.

A series of case meetings and investigations resulted in inconclusive findings. An August 2018 complete staff work report by the Guiguinto CENRO also said SHC denied knowledge of the incident. The office confirmed to Rappler in October 2020 that the case was closed since no perpetrators were identified in barangay and police investigations.

Mangroves are a vital resource, especially for coastal communities. They serve as a natural coastline protection from floods and storm surges, help in preserving biodiversity, and mitigate climate change. At least 8 mangrove species which can typically be found in Manila Bay are present in Taliptip, according to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) Central Luzon.

“With this [land development] project, in terms of fish production, the effect is minimal. We’re more focused and worried if majority of the mangrove area will be affected as it is a spawning ground for fishes. We believe deeper studies must be conducted to understand the effect of building such big infrastructure [airport],” Neil Catibog, officer-in-charge of the Fisheries Management Regulatory and Enforcement Division of BFAR Central Luzon, said in a mix of English and Filipino.

According to the agency, many of the fishponds covered by the land development project are privately-owned, submerged fishponds. BFAR Central Luzon maintains only one fishpond under the Fishpond Lease Agreement, a 25-year contract with citizens to develop government-owned lands. Most of the previously leased fishponds have been turned over by BFAR Central Office to the local government for preferential use.

Since SHC has possession of fishponds and private lands in Bulakan, the displaced fisherfolk have been looking for alternative fishing grounds. There are 2,171 fisherfolk in the municipality who mostly thrive on small-scale fishing, based on BFAR Central Luzon’s fisherfolk registration data.

Increasing vulnerabilities

Fisherman Damario Gomez*, one of Ramos’ siblings who migrated with her to Taliptip in 1986, also demolished on his own, his home in Sitio Dapdap last March. Together, they immediately relocated with other displaced family members to another sibling’s home in Bulacan.

Constrained by the pandemic and a landlocked town, Gomez remained jobless and incurred debts for almost 4 months. When restrictions eased in July, he moved to Malabon City, one of the Metro Manila areas bordering Manila Bay, to continue his livelihood.

“Kapag nawala ang pangisdaan, parang isda na inalis mo sa dagat [ang mga mangingisda] kaya napakahalaga sa amin niyan,” said Fernando Hicap, national chairperson of small fisherfolk federation Pambansang Lakas ng Kilusang Mamalakaya ng Pilipinas (Pamalakaya).

(If access to fishing grounds is taken away, the fisherfolk are like fish taken from the sea. That’s why it’s so important to us.)

A 2019 Pamalakaya initial report had said the homes and livelihood of an estimated 20,000 families across coastal communities of Barangays Taliptip, Bambang, Bagumbayan, and Perez in Bulakan, Bulacan would be affected by the aerotropolis project. But Hicap argued actual numbers are difficult to place since countless vendors, middlemen, and informal settlers also depend on the sea.

Fisherfolk are one of the basic sectors with the highest poverty incidences (26.2% as of 2018) in the country, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority. In a September 2020 situation report on small fisherfolk affected by the COVID-19 lockdown, Hicap asserted that the continually unresponsive government policies, especially during the pandemic, have further marginalized the sector.

This is true for Gomez, whose fear of hunger drove him to take his chances in the Malabon shores. But the minimal catch in the bay area motivated him and other fishermen to return to Sitio Dapdap’s productive fishing grounds. Gomez managed to fish in the Taliptip coastal for around 3 weeks in August until the military allegedly prohibited them from working in the vicinity.

In September, Gomez transferred to Quezon City – his third relocation since being displaced from Taliptip – to resume construction work he had left behind decades ago for the sea. Now a senior citizen, Gomez thinks he can last only two to 3 years in his current job.

Environmental archaeologist Vito Hernandez, who has researched on different reclamation works in the country, said that the continuous, massive displacement of fisherfolk communities affects long-term cultural changes.

When small fisherfolk who supply goods in wet markets are deprived of their livelihood, the food source of many common Filipinos is also threatened. Labor and food security issues only further exploit the already poor and vulnerable sectors, he emphasized.

“Small fisherfolk are [independent and] sustainable. They fish for themselves, their families. The extra, they sell it in the market. Those fishermen working for large commercial vessels, who do they fish for and sell to? They don’t sell in the market. That (catch and income) goes to the bigger middlemen. The question there is, who is benefitting?” Hernandez said in a mix of English and Filipino.

Development for whom?

On October 12, a little over a month after the House’s hasty approval of House Bill No. 7507, the Senate granted San Miguel Aerocity Incorporated (SMAI) a 50-year franchise to build and operate the Bulacan aerotropolis. This bill that lapsed into law (Republic Act No. 11506) on December 20, 2020, gave the conglomerate a 10-year tax exemption during the construction period. Income and real estate tax exemptions will also be in place for the remainder of the franchise term unless the Bureau of Internal Revenue has established that SMC has completely recovered its investment costs for the P740-billion airport – the single-largest project investment in Philippine history – as well as the airport city.

Both House and Senate lawmakers unanimously welcomed the SMC-fully funded project expected to contribute to the economic growth of both Bulacan and the country, as it is projected to generate at least one million jobs and attract foreign investors in Central Luzon.

In a written statement sent by the Department of Transportation (DOTr) to Rappler, the agency said that the economic, technical, and financial viability of the airport project had been evaluated before it was endorsed to the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) Board Investments Coordination Committee, and that the venture is aligned with the government’s development objectives.

The Bulacan airport, a gateway near Metro Manila and also accessible to Central Luzon, is a “future-proof long-term solution” to aviation issues in the region, benefitting Filipino travelers, overseas Filipino workers, tourists, and investors, SMC said in an e-mail to Rappler.

The company also said that the environmental and geohazard risks are being factored into the design and engineering process. Among other measures, SMC is considering dredging and increasing the carrying capacity of major rivers Taliptip, Meycauayan, and Sta Maria to mitigate flood risks.

“Our overall plan for the airport project includes preserving biodiversity through whatever necessary means. We have tapped global consulting firm Mott Macdonald to conduct a more comprehensive biodiversity baseline study,” SMC added.

Last December, SMC announced it contracted the Royal Boskalis Westminster N.V. for the land development of the project site. The Dutch firm will begin preparatory work in the first quarter of 2021.

But many fisherfolk, environmentalists, and scientists continue to oppose the reclamation project due to SMC’s lack of transparency and genuine community consultations, and the project’s unalterable destruction of ecosystems.

In its geohazards study, UP NIGS argued that even developed countries face difficulties in designing engineering solutions, citing Japan’s Kansai International Airport as an example of large infrastructure built on reclaimed land and which suffered from land subsidence.

Various organizations have also criticized the grant of a legislative franchise to SMAI – a first for an airport in Philippine history. Think tank Infrawatch PH said in a statement in October that the government is projected to lose at least P22 billion in taxes for the preliminary 10-year operation of SMAI. The provision of a franchise and tax perks discourages market competition and puts the country’s airport industry at a disadvantage, it added.

Baleng Lagos, assistant professor at UP Diliman’s Department of Community Development, said there are also unaccounted costs of reclamation which should be considered despite being excluded in discussions, since cost-benefit analysis isn’t required in the EIA.

According to the August 2020 counter EIA which Lagos also developed with the Taliptip and Obando fisherfolk, these include costs of livelihood, aid and social amelioration, health impacts, support for mental health, and loss of environmental resources, among others.

Lagos, who works on fisherfolk issues and their reclamation struggles, said that the pioneer counter EIA has been used as a reference for the judicial affidavit included in the recent writ of kalikasan plea filed by affected Taliptip fisherfolk, civil society groups, and international non-profit organization Oceana with the Supreme Court last December 15 to challenge and stop the Bulacan airport project.

Threat to waterbirds, too

Apart from being a significant fishing ground and a home to fisherfolk families, Manila Bay is an abode to many migratory birds, including 4 globally threatened waterbird species. Wild Bird Club of the Philippines (WBCP) vice president Cristina Cinco said that this rich biodiversity can be attributed to the Philippines being a vital pathway along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, one of the world’s 9 major flyways where migratory birds pass.

Cinco, who took part in a Wetlands International research published in October 2018, said that the aerotropolis project site had been declared by BirdLife International as an important bird and biodiversity area. BirdLife International is the world’s largest nature conservation partnership that has over 100 member countries, including the Philippines’ Haribon Foundation.

The research found that the northern portion of the bay had an increasing waterbird population from 2003 to 2018, and around 171,500 to 208,500 waterbirds fly to Manila Bay during the mid-winter season from December to early April, according to studies conducted from 2016 to 2018. A total of 24 black-faced spoonbills – an endangered species – were also spotted in Taliptip on January 11, 2020.

Ecology and conservation expert Carmela Española, a founding member of the WBCP, said in the writ of kalikasan petition that the construction of the Bulacan airport will not only potentially displace and collapse the bird ecosystem, but also cause possible bird strikes.

A bird strike is “a collision between an airborne animal and a man-made vehicle” that could spell expensive repairs to aircraft, and cost animal and human lives. Española added that bird strikes, an already increasing occurrence in the Philippines, are highly likely to happen in the NMIA because it is surrounded by wetlands.

Waterbirds, known to be bioindicators of a good environment, are dependent on wetlands that are abundant in Manila Bay. The DENR’s Biodiversity and Management Bureau had also previously identified the bay as a key biodiversity area – one of the country’s priority sites for conservation.

Former DENR undersecretary and environmental law professor Tony La Viña, who has been working on Manila Bay issues for more than 30 years, explained: “Population drives what happens to Manila Bay. Just because there’s been [a] great increase of people living literally by the sea and [of] very big establishments, including reclaimed areas, the pollution has grown tremendously – ironically from 2008 when the Supreme Court ordered the cleanup of Manila Bay.”

He added that these factors should be considered in the construction of the airport, which would bring in more people and concrete structures to Bulakan and surrounding communities. If these issues are not addressed, La Viña said that the venture could just add to waste production, a perennial problem in the bay’s rehabilitation.

Amid challenges in its waste cleanup, Manila Bay still has thriving biodiversity. It remains a rich source of food and livelihood for coastal communities across Metro Manila, Cavite, Bulacan, Pampanga, Bataan, and non-coastal communities in Laguna, Nueva Ecija, Tarlac, and Rizal. This has prompted fisherfolk, environmentalists, and concerned scientists to challenge the reclamation projects in the area.

Land issues

There are 22 reclamation initiatives in Manila Bay as of January 2021, according to the Philippine Reclamation Authority (PRA). Of the 22, only 4 projects have a conditional notice to proceed. But the Bulacan aerotropolis isn’t on the list as SMC hasn’t applied for a permit.

“San Miguel (Corporation) or Silvertides’ initial stand is, they hold titled properties. When is it considered reclamation? Reclamation is filling up of public domain. When we say public domain, it is still owned by the national government. It’s not yet alienable and disposable,” said Joseph Literal, manager of PRA’s environment management department, in a mix of English and Filipino, while explaining why the agency is currently not in the picture.

The writ of kalikasan petition, however, says that 61% or 1,521 hectares of the aerotropolis project area is either permanent forest land or under forest land classification, based on analyses conducted using the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority data. It also states that fishponds in mangrove areas are classified as forest lands, and that a portion of the project site is part of the Bulacan Fishing Reservation under Republic Act No. 4701. These findings mean the land is public domain.

Rappler reached out to the DENR Central Office in October for an interview or comment on the environmental and land issues, but it has not directly addressed the queries in its written response.

In a brief written response dated November 25, the agency said: “The NMIA is still proposed and the ECC (environmental compliance certificate) for the project is subject for screening/initial review only. All activities and meetings of the EIARC [review committee] were suspended pending the conduct and submission of the required public scoping/consultation/hearing.”

The DENR added that stakeholders’ concerns will help form the revised environmental impact statement that will be submitted for review. Yet all directly affected Taliptip residents have already left the coastal sitios.

Although the PRA is the coordinating and regulatory body for reclamation projects around the country, under the law, only the president of the Philippines can approve such initiatives.

In early 2020, President Rodrigo Duterte said that to protect the environment and the public’s welfare, he will not allow massive reclamation projects in Manila Bay to be led solely by the private sector. Prior to this declaration, the Office of the President signed a 2019 administrative order expediting the bay’s rehabilitation and creating a task force for it, with the DENR Central Office as lead agency.

The national government is also investing in the formulation of a Manila Bay Sustainable Development Master Plan (MBSDMP), a guide for decision-makers in evaluating projects and activities within and in areas affecting the bay. This ongoing effort was spearheaded by the NEDA, with support from the Dutch government.

In an MBSDMP updated action plan and investment report dated August 2020, NEDA warned against building any infrastructure within northern Manila Bay, saying that “any flood protection measure or development project to be implemented now [is] likely to become dysfunctional in the next decades” due to the land subsidence rate and the sea level rise.

But in April 2018, the NEDA Board, chaired by Duterte, had already approved the Bulacan airport project as part of the administration’s Build Build Build program.

“There are many laws – reclamation laws, environmental protection laws, Supreme Court mandamus. Those should have been enough to end this issue. The implication is our institutions aren’t working,” Eco said in a mix of English and Filipino.

“That’s one of the factors contributing to the vulnerability of a community or a person – the governance structures. When the governance structures are weak, you are more prone to disasters. You have higher disaster risks,” he said.

Former Taliptip resident Seraphina Ramos shared Eco’s sentiment and could only call on local officials to prioritize disaster preparedness and long-term measures that will address destructive flooding in Bulacan. – Rappler.com

*Interviewees’ real names have been changed to protect their identities.

This story is produced in partnership with Oceana Philippines.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Vantage Point] Bug and rodent infestation in NAIA: Why aren’t we surprised?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/tl-bugs-and-rodents.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.