SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The Philippine government spent a total of P72 million in taxpayers’ money to review the operations of mining companies under a public contract, but none of the project-level reports are publicly available.

The Mining Industry Coordinating Council (MICC) Secretariat told PCIJ that the mining review reports or the company-level mining reports could not be shared to the public for three reasons:

- “The said data/information requested is/are covered by Executive Privilege;

- The report is still being used by the government to develop mining-related policies; and

- The MICC has entered into a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) with the mining companies covered by the review.”

The reasons above, the MICC Secretariat said, are based on Executive Order 2, s. 2016 or the Freedom of Information (FOI) Order and the Office of the President’s Memorandum on the Inventory of Exceptions to EO 2.

Transparency advocates see no reason for the mine review to be kept out of public scrutiny.

Lawyer Eirene Jhone Aguila, co-convener of the Right to Know, Right Now! (R2KRN) Coalition, pointed out that the mines obtained special concessions from the state, which they had applied for.

“You cannot expect to have regulation if you’re not open. How can people regulate you if sarado (you’re blocking the information)?” she said.

Aguila said disclosure afforded everyone the opportunity to check if the findings were right or wrong. This, she added, was the reason people who believed they didn’t do anything wrong welcomed any investigation.

Jenina Joy Chavez, also an R2KRN co-convener, said executive privilege was one of the most abused FOI exceptions. The reason the government was using the mine review reports to develop policies might be related to “matters covered by deliberative process privilege,” which is among information covered by executive privilege. But it’s not as if the government was deliberating whether one is guilty or not, especially since the government already possessed the findings and reports, she said.

“Pero kung policy, that should be open, kasi policymaking is an open process. It’s not a good interpretation of that exception,” she said.

As for the NDA, Aguila said it was a circumvention of the commitment of the state to open the books. “You cannot waive that on behalf [of the people] because when the state demands for you to be open, the state does it as representative of the people,” she said.

She also said mining firms did not have the right to dictate what information could be made publicly available. “It’s not theirs. It’s for us. It’s for the state there. That’s the concept,” she said.

Aguila said it was important to highlight that the reports were an assessment of mining firms under a public contract.

“This is not a private contract… Here we’re talking about state resources that are highly regulated. It’s not for the private parties to say what the state and the public can look into,” she said.

P72M mine review, post-Lopez audit

In February 2017, the MICC issued Resolution 6, which ordered a “multi-stakeholder review” of existing mining operations, following the suspension and closure of 28 mines led by the late Environment Secretary Gina Lopez.

The resolution was issued after the mining firms suspended or closed by Lopez appealed before the Office of the President to reconsider the DENR orders.

Lopez then questioned the legal basis of the MICC’s review of her department’s orders, which, through the Mines and Geosciences Bureau, is responsible for regulating the mining industry. The MICC review was initiated “to appease them [miners],” the late secretary said in a February 10, 2017 interview on ANC.

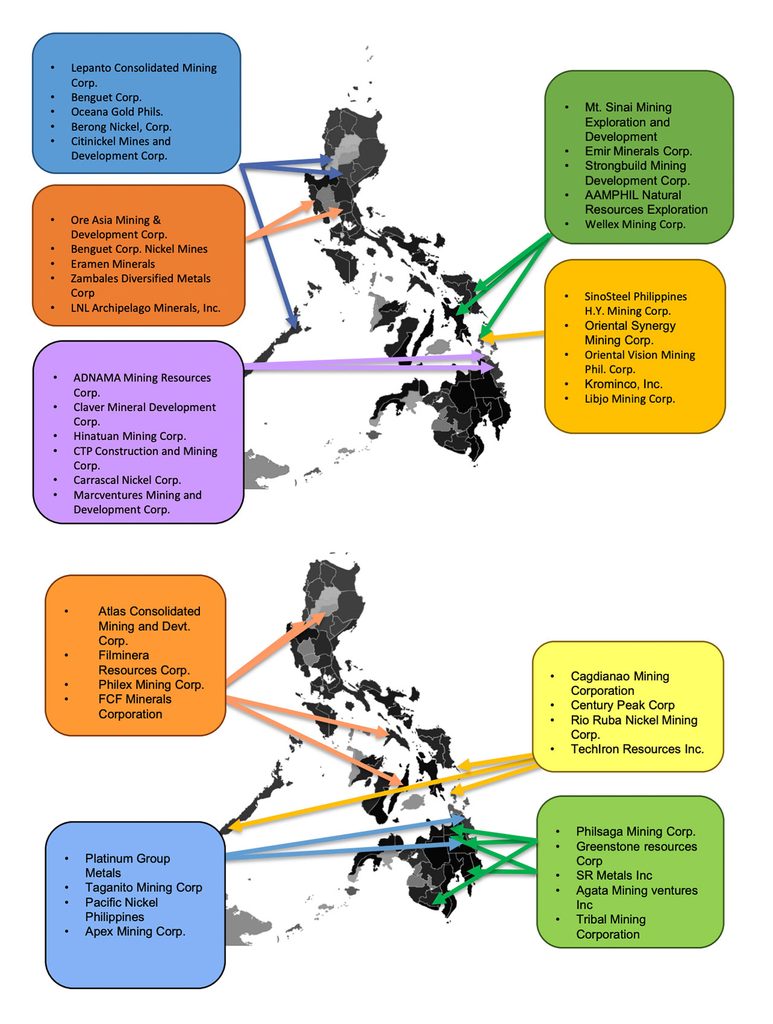

To date, the MICC has completed two phases of the mining review, from February 2018 to December 2020, covering a total of 45 large-scale metallic mines operated by 43 mining companies.

A third phase is underway. It covers quarry operations across eight regions and metallic mines in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. The third phase started in January 2022 and is expected to be completed by May 2022.

A total of P45 million was spent on the first two phases of the MICC mining review, which was co-funded by the DENR and Department of Finance (DOF).

A total of P27 million was allocated to Phase 3, according to the Mines and Geosciences Bureau. (See Table 1 for breakdown of the items and cost for Phases 1 and 2.)

The full reports from Phases 1 and 2 of the mining review were classified as “confidential,” and could only be accessed through an official request with the DENR, the owner and user of the reports. However, following the MICC protocol for the release of the results of the mining review, only mining companies subjected to the review were entitled to a copy of the report.

This, according to the MICC Secretariat, “will help them directly address the specific findings in the reports within their purview and improve their compliance with existing laws.”

PCIJ’s January 2021 request for information on the status of the MICC review with the Office of the President yielded no results as it refused to disclose information on specific cases.

On its second attempt to seek updates on the review in March 2021, PCIJ was advised by the office to ask the DENR and DOF instead.

PCIJ’s third attempt in February 2022 to get updates and obtain copies of the reports from the MICC Secretariat was denied on the basis that the company-level reports were under executive privilege.

PCIJ was told that the MICC would publish a technical paper and a policy brief to provide the public with more information on the results of the review.

The technical paper is expected to discuss technical insights on the mining sector. The policy brief will provide an overview of the mining sector from a policy perspective, and list down challenges and reforms necessary to develop the sector.

These documents were supposed to be released in March 2022. No news outlet has reported about it as of March 31.

MICC mine review method

What the MICC has disseminated so far are the key results and findings of Phases 1 and 2 through multi-stakeholder forums held in June and August 2021. View the MICC summary results here.

The review considered five aspects in assessing the performance of mining companies:

- “Technical aspect looks into the appropriateness, adequacy, and efficiency of technology employed, based on international industry standards.

- Legal aspect covers the companies’ compliance with mining laws, rules and regulations, and other applicable laws, and the adequacy of the previous mining permits, licenses, and contracts issued to start the mining operations, and other applicable laws.

- Social aspect includes the mining operations’ impact on the host community/ies and their populace, as well as indigenous peoples, in terms of availability and access to social services and facilities;

- Environmental aspect examines the impact on ecosystem and biodiversity in the mining as well as in adjacent areas; and

- Economic aspect focuses on the societal costs and benefits of mining and quarry operations, particularly their contribution to or effect on employment, livelihood, local revenues, and poverty alleviation.”

A scoring system was developed using a detailed scoring procedure and overall rating index. In classifying the mining operations, each mining operation is rated (i.e., good, needing minor corrections, major reforms, or poor) by experts based on the MICC guide questions and indicators for each of the five aspects.

A score greater than 2.8 implies good or acceptable performance; between 2.0 and 2.8 means a minor correction; between 1.0 and 2.0 requires major reforms in operations; and less than 1.0 is considered poor or not acceptable.

The MICC formed four to five Technical Review Teams (TRTs) and selected an overall team leader, who integrated the results of the review. Each TRT is composed of five experts based on sustainability aspects. They come from different fields, such as mine engineering/geology, law, environmental science and management, sociology/human ecology/community development, and economics.

The experts were selected based on MICC screening criteria, such as academic qualification, years of relevant experience, and trainings attended or conducted. PCIJ reached out to some of the experts, but the requests were either denied or not responded to.

Mine review summary results

A review of the summary results for each of the five aspects showed that the majority got scores above 2.0, which meant that only minor corrections were needed. All the mines also scored higher during Phase 2, which indicated improvement. But it’s difficult to understand what measures were taken by each mine because they were not identified.

In the “Key Recommendations” presentation, the MICC found that “there was basis for DENR actions but there were efforts to rectify and correct errant practices, except for three companies.”

It said that reasonable time should be allowed for rectification before closure is recommended as a final and last resort.

The MICC also found a few cases, two to three, where rectification was likely to be difficult because of insufficient capitalization and low metal prices.

Innovative practices of some firms should be recognized and may be adopted by other sites, the MICC also said. These mines, however, were not identified.

Vincent Lazatin, convenor of Bantay Kita, said in a statement that the scores didn’t seem to be supported by the findings and recommendations. “Given some of the findings and recommendations I’m surprised that the scores were as high as they were in some cases. It would help to know exactly how the scoring was done.”

“These generally high scores give little reason for companies and the government to improve. And if we read the numerous recommendations, there is a lot of room for improvement,” he said.

Lazatin found the environmental dimension of the report most alarming. According to the MICC presentation, key findings for Phase 2 included:

- absence of a comprehensive environmental impact assessment/statement results;

- insufficient analysis of climate risk and faulty siting of some facilities;

- lack of or limited biodiversity monitoring;

- absence of or lack of clarity in success standards;

- soil erosion/siltation issues;

- problems in water use efficiency;

- delays in tree-cutting permits;

- issues in waste handling and disposal as well as earth-balling; and

- low budgets for environmental protection and enhancement.

“Without the ability to adequately monitor environmental compliance and impacts, without the ability to take the necessary measures to protect the environment and the interests of the country, what business do we have to be granting companies the privilege to engage in extractive activities?” wrote Lazatin.

He also said that the recommendations for the environmental dimensions were so basic that “it really leaves one wondering why many companies are allowed to operate at all.”

It would be helpful if the project level reviews could be made available as they would be particularly valuable to the communities, Lazatin said.

The MICC presentation itself noted that “public disclosure of environmental performance of mining could build social trust.” – Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism/Rappler.com

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network (RIN). To learn more about forest stories across the globe, visit the RIN fellows’ page here.

Elyssa Lopez, Martha Teodoro, Sofia Bernice Navarro, Ma. Cecilia Pagdanganan, and Kyla Ramos of PCIJ contributed research to this story.

Infographics by Karol Ilagan

This piece is republished with permission from the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.