SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Before the Philippine eagle became the national bird and the quintessential symbol of Philippine wildlife, very little was known about the raptor.

It was in 1965 when Dioscoro Rabor, also known as the Father of Philippine Wildlife Conservation, alerted the public about the Philippine eagle’s (Pithecophaga jefferyi) endangered status, which started the race to save the bird from extinction. Illegal hunting and continued denudation of Philippine forests contribute to the dwindling numbers of this majestic bird.

Rabor called for a conference with the International Union for Conservation of Nature in Thailand. With the help of renowned conservationist Charles Lindbergh, Bob Kennedy of the Harvard Museum of Natural History, and a slew of peace corps volunteers, a breeding program was established near Mt Apo, the country’s highest peak, in 1978. The Philippine Eagle Foundation, the leading conservation group, was founded the same year.

Mindanao is home to half of the species’ population, and no more than 400 breeding pairs remain in the wild at present.

With researchers and scientists knowing very little about the eagle, the foundation sent staff to major raptor centers around the world. Some of the first things established about the eagle were its fiercely territorial behavior and highly selective attitude towards choosing its mate. This made the breeding program and attempts at artificial insemination a slow and arduous process.

As early as 1987, the foundation had successfully produced eggs from natural pairing. But limited knowledge on breeding, incubation periods, and taking care of eggs properly, among others, laid out limitations to the success of artificial insemination.

The birth of hope

After 14 years, the hard work of captive breeders paid off when, in 1992, the first ever Philippine eagle bred by artificial insemination was born. He was named “Pag-asa,” the Filipino word for “hope.” He was the first offspring of Diola with her mate Junior, a male eagle from Agusan.

The eaglet had a hard time hatching. Completely breaking the shell took many hours, and when the staff realized he was having difficulty, then senior keeper Domeng Tadena helped break the shell. Tadena later became the the Philippine Eagle Foundation’s deputy director for its conservation breeding program.

As he came out of his shell, the staff found a healthy baby bird covered in white feathers, as if blanketed in snow.

21 DAYS OLD. Pag-asa, a newborn chick, gave hope to the conservation efforts in the country. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

It was Pag-asa’s birth in 1992 that became the major milestone for the foundation’s efforts at artificial insemination – the first in the Philippines.

But the staff did not arrive at this success without roadblocks.

Dennis Salvador, the executive director of the Philippine Eagle Foundation, told Rappler that before their success with Pag-asa, the government tried to close down the breeding program because “they thought the captive breeding program isn’t working.” At the time, Jun Factoran, a staunch anti-Marcos activist, headed the environment department.

Since then, the foundation had to rely on the faith of its staff, donations from the private sector, and the media’s amplification of the eagle’s plight.

“When people realized we were serious, support began to come in,” said Salvador.

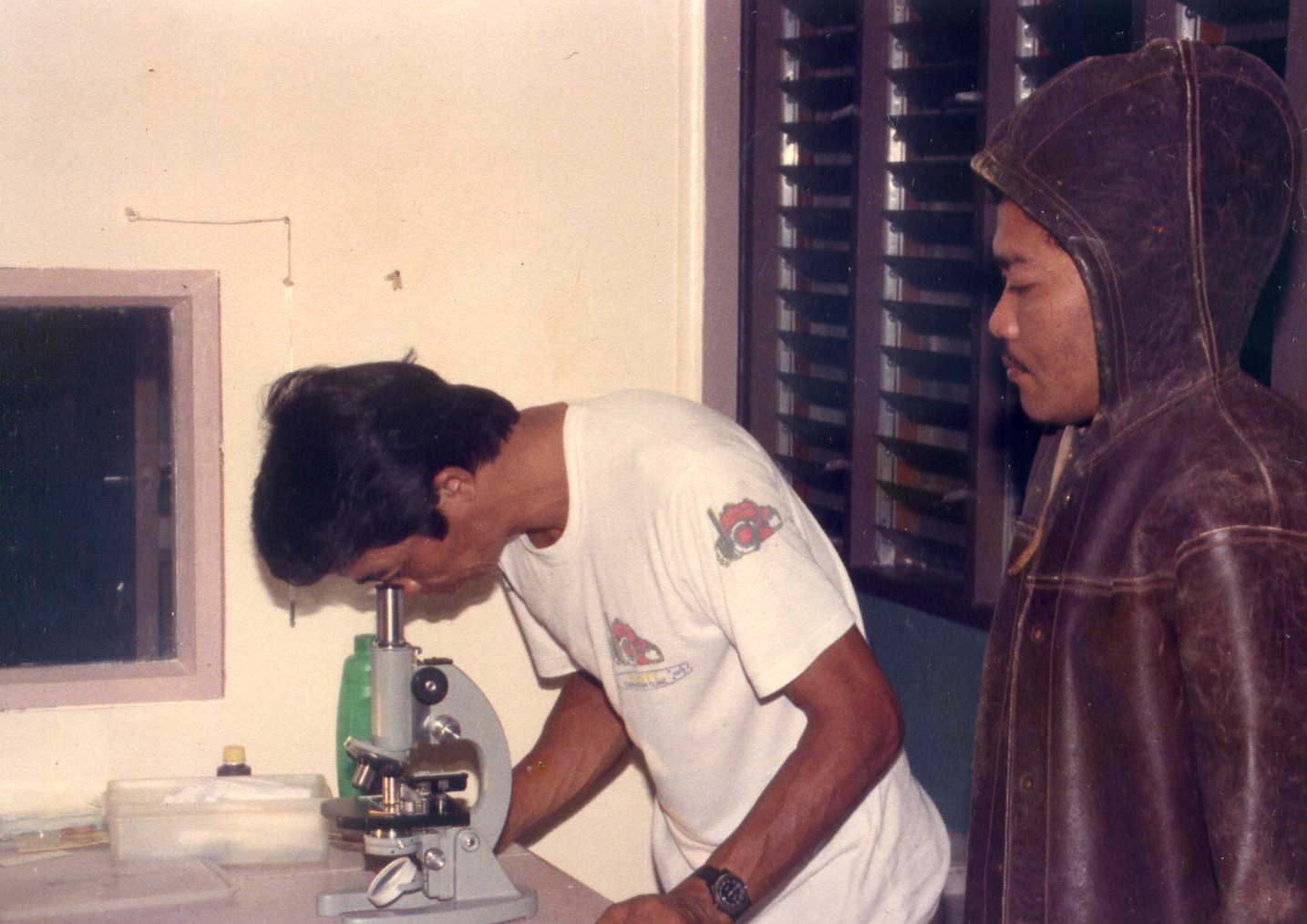

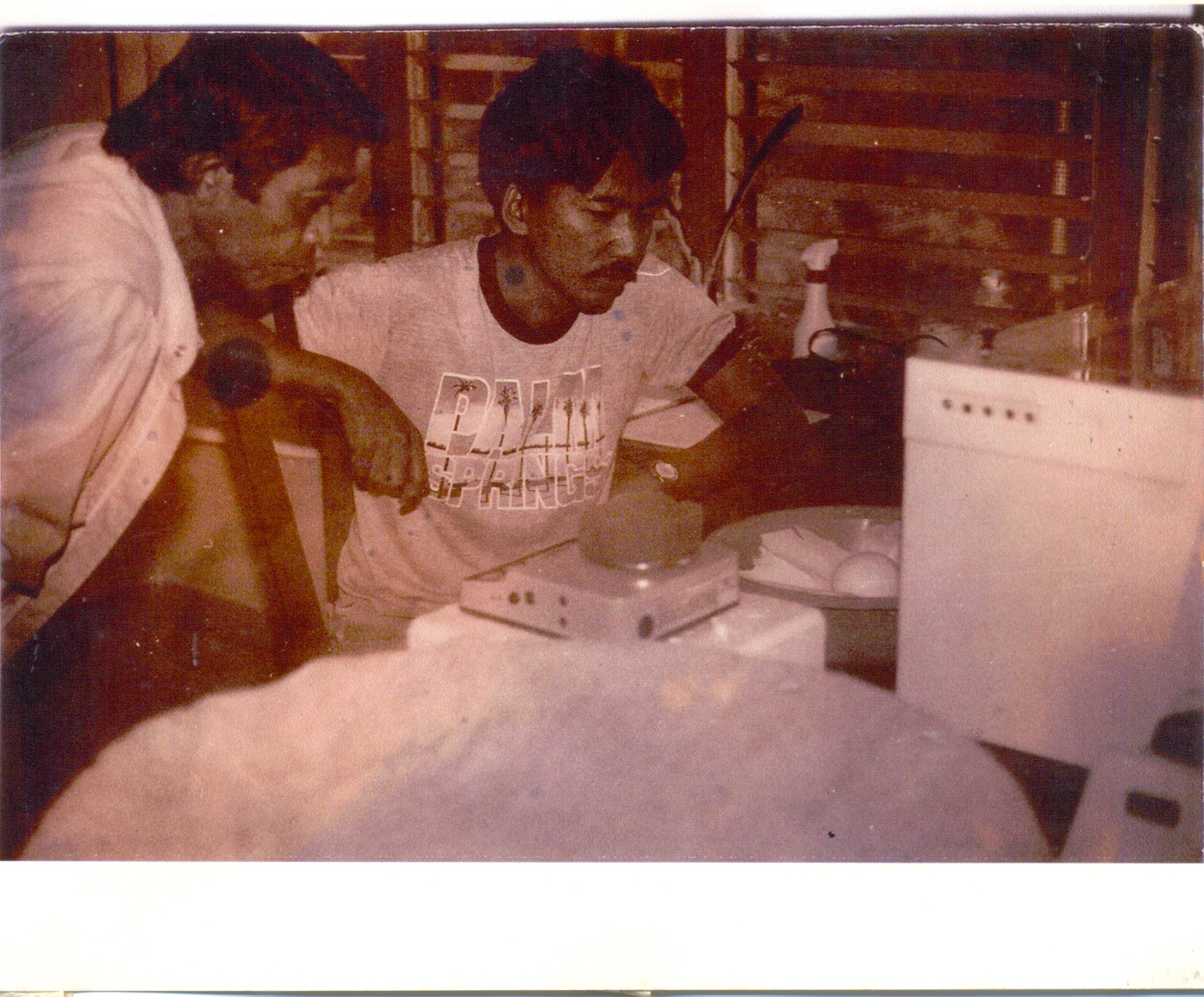

PIONEERS. Domeng Tadena (L) and Dennis Salvador (R) dedicated most of their lives to the rescue and conservation of the haribon. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Because of the withdrawal of support, the foundation’s staff, who were working long shifts and were always on call, did not receive their salaries for a year before Pag-asa came.

So not only did the eaglet represent hope for the conservation of its species, but Pag-asa was a lifeline for many of the staff and supporters amid the absence of government aid.

Pag-asa’s birth was the making of history.

“Because of the success, what people saw of the work that went behind it, people began to support us. I’m proud to say that people who supported us then continue to support us now,” Salvador said.

Until now, the foundation has not received any support from the environment department, according to Salvador, even though the main subject of its conservation efforts is of national significance.

Pag-asa’s legacy, and the future of conservation

Pag-asa lived 28 fruitful years before succumbing to infections associated with trichomoniasis and aspergillosis on January 6. He would have turned 29 today, January, 15.

He sired an offspring named Mabuhay (Filipino for “long live”) that hatched on February 9, 2013. But Pag-asa left not only a chain of succession, but the scientific knowledge and lessons for future breeding of endangered raptors.

Affirmed by the possibility of rearing birds through artificial insemination, Salvador said this underscored the potential that captive breeding “is a viable tool for augmenting wildlife population.”

Scientists, advocates, and researchers have amassed comprehensive knowledge about the raptor throughout Pag-asa’s life and the lives of the eagles that followed after him.

Raptor biologist Jelain Gan said that today, the Philippine eagle is the “most researched, most understood, most well-known among raptors.”

Gan, who is also working as a biologist and instructor at the University of the Philippines-Diliman, said that amid deforestation and the extinction of many species, Pag-asa’s life is testament that population rebound is possible as long as there are conservation efforts and research in place.

PERCHED. Pag-asa perched on a keeper’s hand in Davao. He was 3 ft tall and had a wingspan of 7 ft. Photo courtesy of Philippine Eagle Foundation

Today, Philippine eagles are found in Leyte, Samar, and Luzon. Many scientists thought Philippine eagles did not exist in the Cordilleras, but the first active eagle nest in Luzon was actually found in Luna, Apayao.

The preservation of wildlife continues to be a serious undertaking. In 2020 alone, the foundation rescued 7 eagles – a number considerably bigger than their average of two rescues per year.

The coronavirus pandemic especially emphasized the pressing need to conserve endangered species and rehabilitate forest cover. Scientists had attributed animal-borne diseases from habitat loss, deforestation, and the mingling of wildlife with humans.

“If we take too much from nature, far beyond what it could actually provide without compromising itself, [this pandemic] shows us that it can bite us back big time,” said Salvador.

The organization believes the status of the Philippine eagle is inextricably linked to the environment, and the success of its propagation is very telling of the state of Philippine forests and wildlife.

Salvador said the conservation of endangered animals and the reforestation of natural habitats can save many human generations from future health crises and pandemics.

“Wildlife and forest habitat are natural systems that in turn protect our people. Capital natin ito para sa future (This is our capital for the future),” he added. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.