SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The port city of Tanmen, China, may be a small fishing town that’s home to just over 30,000 people, but it’s also a hugely strategic site in the battle for sovereignty over the South China Sea. This is a battle that affects hundreds of millions of people across the region.

Located in the Qionghai district on Hainan island, the southernmost province of China, Tanmen is crucial to the country’s claim to a huge swathe of the resource-rich South China Sea. These are claims that China’s maritime neighbors – like Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam – have contested for years.

Caught in the middle of this international geopolitical conflict – one where the United States has also weighed in – are traditional fishers like Li Qin. Many like him across the South China Sea have become key figures in their countries’ sovereignty claims, often facing off against each other on the frontlines.

In January 2021, Li and his crew had just returned from fishing at Xisha Islands (the Chinese name for the Paracel Islands) when a journalist from Initium Media, working with the Environmental Reporting Collective (ERC), caught up with him.

It’s always a spectacle when a large fishing boat like Li’s returns to Tanmen port, which is located in the center of the city. Tourists and locals alike gather around as the crew pulls the fresh catch from the boats into waiting pickup trucks, and some tourists even jump aboard the boat decks to take a closer look.

This has been a ritual for Li for 40 years. At 15, he first joined his father and brother as they went fishing in Xisha, Zhongsha Islands, and Nansha Islands (the Spratly Islands). For years, Tanmen fishers were encouraged by the government to fish there, to reinforce China’s claim that they had done so since ancient times.

But these days, despite the relatively good catch, things are getting complicated. Fishing in Nansha is becoming increasingly difficult due to new regulations, which Li says are aimed at reducing the number of boats and “changing the method of production.”

Wooden boats like Li’s, despite being relatively large by Tanmen standards at 100 tons, are no longer accredited by the government. Larger steel boats are now preferred, and traditional fishing communities like Tanmen’s are being encouraged to focus on more tourist-friendly activities like catering and bay fishing.

The main purpose of this change in “method of production,” according to Tanmen fishers interviewed by Initium, is what they called the “special project” – defending their country’s claims over the South China Sea.

From fishers to maritime militias

In 2018, a Tanmen fisher named Wang Shumao was given an extraordinary honor. He was named one of China’s “Reform Pioneers,” alongside Yuan Longping, a Chinese agronomist known for developing the first hybrid rice varieties; and Tu Youyou, the first Chinese Nobel laureate in physiology or medicine.

In June 2021, Wang was honored once again, this time with a medal awarded in conjunction with the Chinese Communist Party’s 100th anniversary.

His contribution to the country? Defending its territorial claims on the South China Sea, as the deputy commander of the Tanmen Military Militia.

The Tanmen Military Militia consists of fishers who are reportedly trained by the navy, and its main role, according to a public statement by a Tanmen official, is to “safeguard rights at sea.”

For example, in 2012, when the standoff between China and the Philippines over the Scarborough Shoal (known in China as Huangyan Island) began, Wang and a fleet of boats from Tanmen joined the effort to block Filipino fishers from entering the area. The conflict first escalated in April 2012, when a Philippine warship arrested 11 Chinese fishermen – all from Tanmen – in the area, with a Filipino official issuing a statement that Scarborough Shoal “is an inseparable part of the Philippines.”

In 2014, when the Vietnamese government sent boats to deter the China National Offshore Oil Corporation from drilling in Xisha, the Chinese government responded by creating a “cordon” of boats around the oil rig, with Wang leading 10 fishing boats. The Chinese embassy in Vietnam reported over 1,000 collisions between boats from the two countries during this standoff.

To illustrate just how important the Chinese government deems the Tanmen Military Militia to be, President Xi Jinping made an unprecedented visit to Tanmen to meet with the fishers-turned-militiamen. During his visit, he urged them to “build big boats, blaze the far sea, catch big fish.” This slogan is now plastered on a billboard at the town’s main intersection.

Our journalist from Initium Media attempted to speak with Wang at the Tanmen branch of the Chinese Communist Party, but was told he had gone for a meeting in the province as a delegate of the National People’s Congress. We were also asked to submit a request with the Propaganda Department, as unannounced interviews were not permitted.

In 2016, a journalist from Al Jazeera had inadvertently spoken to Wang while doing a report in Tanmen, not realizing who he was. According to the Al Jazeera report, Wang had denied the existence of a “maritime militia,” even though the journalist had just seen a group of 40 or so men in camouflage uniforms undergoing training outdoors.

Most of the other fishers we spoke to around the docks also seemed to avoid using the term “maritime militia.” When asked about the trips to Nansha Islands to defend China’s territorial claims, they simply referred to it as a “special project.”

In China, a militia is legally defined as “an armed organization of the population that is not separated from production.” It is a civilian force organized by local governments or enterprises, made up of ordinary citizens who would become soldiers in times of war.

Militias do not have professional status but are mobilized during emergencies, like the 1998 Changjiang River flood or the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan. In these cases, militias participated in rescue operations, along with the People’s Liberation Army and the police.

According to an official statement, the Tanmen Maritime Militia is formed on the basis of the “Fisheries Militia sub-branch.” In addition to fishing operations in the South China Sea and sovereignty maintenance, its most important role is to rescue fishermen during typhoons.

Walking along the docks in Tanmen, our journalist saw around 20 steel fishing boats docked in the water, all bearing China’s red flag with five stars on their bows.

A local man who works in boat maintenance said the boats are no longer for fishing and are now mainly engaged in “rights protection,” relying on special government subsidies to make money. They normally travel to Nansha for around six months at a time, with a crew of five to six people, earning up to 5,000 RMB ($770) a day in subsidies.

The last time Li Qin, the local fisher, went to Nansha was in May 2020, when China’s annual three-month fishing moratorium began. He set off from Tanmen in his fishing boat with a crew of 20, joining a fleet of more than 600 “special project” boats, which included ships from the neighboring Guangdong and Guangxi provinces.

“Every day was mainly about eating and drinking on board,” said one of Li’s crew members.

“The subsidy is 1,500 RMB ($230) a day, and the amount of subsidy is related to the length of the ship, not the engine power,” said Li, adding that they were given a three-month subsidy of 135,000 RMB ($20,800). He and the crew would also catch fish while anchored in Nansha. “If we didn’t fish, we would lose money.”

There is no publicly available government document stating how the “Nansha special project subsidy” is calculated. According to the Guangzhou-based news magazine, Southern Weekend, a one-time subsidy of 35,000 RMB ($5,400) was given to fishing boats that visited Nansha or Huangyan Islands in 2011, and, on top of that, a trip allowance of 82 RMB/kW ($12/kW) was given based on the boat’s engine power.

In Hainan, it is not unusual for fishers to go to Nansha. Zhang Zhi, who fishes off the coast of Lingshui County in Hainan, said that many of his friends in his hometown of Lingao county sign up for patrolling. “State officials will arrange a few people on a big boat; some of them drive slowly, some anchor at Xisha or Nansha. There’s a one-time paycheck.”

Zhang Zhi added, however, that he does not feel strongly about safeguarding the border, saying that he occasionally encounters Vietnamese fishing boats who ask him for food or to exchange catch.

Zheng Shixi, a former party branch secretary and militia battalion commander in the Yugang community of Sanya City, in the south of Hainan, told Initium Media about his trips to Sansha.

On July 12, 2012, as deputy commander-in-chief, he led 30 fishing boats from the Sanya Nanhai community to the Nansha Yongshun Reef, Zhubi Reef, and Meiji Reef. While they were known as a Nansha fishing fleet, Zheng said they were there for the “protection of rights.”

Shi Lei, another fisher from Sanya who participated in the “rights protection” activities in 2012, told Initium Media that the journey to Meiji Reef took four days and four nights, while the entire trip lasted 18 days. In return, he got a government subsidy of 200,000 RMB ($30,800). He said Sanya fishing boats normally did not go to Nansha for fishing, and he did not catch fish during his trip either.

From fishing to tourism

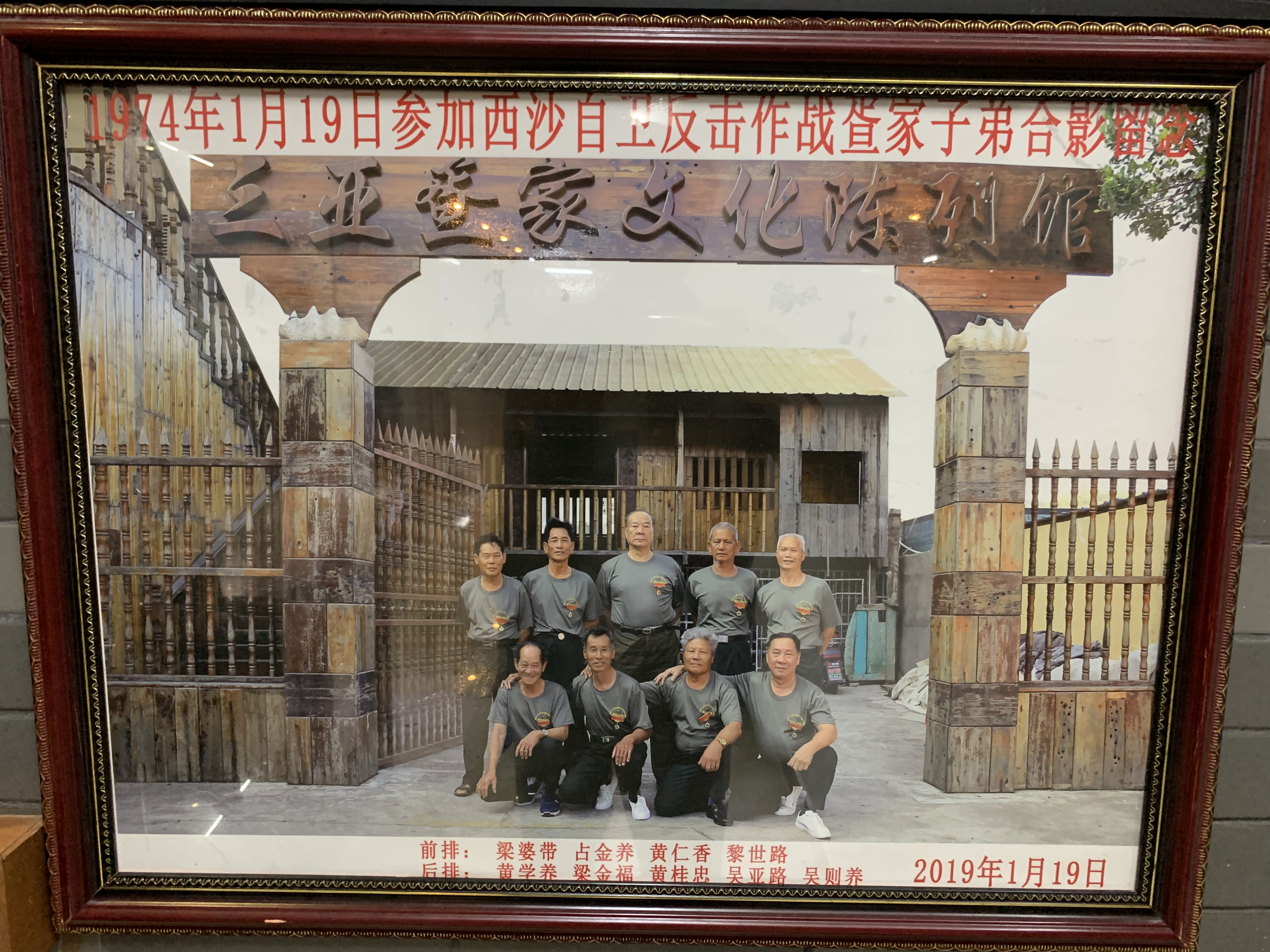

The South China Sea Museum in Tanmen, which has been open for three years, includes a copy of the Changing Sailing Route Book, donated by Huang Jiali, a fisherman from Caotang village in Tanmen.

It is one of many route guides passed down from generation to generation in Hainan. According to Huang, who was born in 1930, this sailing guide contains a route to Nansha. It was handed down from his grandfather to his father, and then to him. Research concerning these books began in the 1970s, and now they are considered by China to be evidence that the Nansha Islands have always belonged to it.

A retired fisher in Tanmen named Wu Hai told Initium Media that his father’s generation had been sailing in Nansha since the 1930s, armed simply with a 20-ton boat and a compass.

“We used to pick up sea snails, coral, sea cucumbers, [and then we] drove the boat to Malaysia or Singapore to sell the goods in exchange for some fabric. There were some people who didn’t come back, and it was very common to sail to the South Seas,” said Wu Hai.

In March 1985, China’s State Council issued directives to “accelerate the development of the aquaculture industry,” particularly through distant water fishing, leading to an increased number of Chinese fishing boats in the South China Sea. Wu started fishing in Xisha and Nansha around this time, in boats weighing around 60 tons. He recalls that most of the islets were still occupied by Vietnam at the time, which meant Wu and his peers had to pay the Vietnamese to anchor and fish.

But winds of change are blowing again. In 2017, the Communist Party of China’s Central Document No. 1 proposed the promotion of structural reform on the supply side of agriculture, calling for the industry to “reasonably control offshore fishing,” “establish a management system for the total amount of marine fishery resources,” and “support fishers to reduce their vessels and switch to other production.”

In 2019, the government of Qionghai district released a report on “strategies for Tanmen fishermen to change production and industry,” focusing on production efficiency, South China Sea rights, the construction of a Hainan free trade zone, and the necessity of “Tanmen fishermen to change production and industry.” The report also states that it is necessary to “guide the old fishing boats to switch to other productions.”

These policies are already creating the desired effect. Out of the 112 large and medium-sized fishing boats in Tanmen that went regularly to Zhongsha, Xisha, and Nansha in 2019, 81 had “special fishing permits,” which are seen as being primarily for defending China’s territorial claims.

With subsidies increasingly focused on larger steel ships that have these special fishing permits, traditional fishers like Li will have to consider switching to other industries. Having once encouraged them to fish in Nansha to maintain sovereignty, the government is now asking them to stop fishing for the same reason.

More tourist-friendly industries have been encouraged, such as catering and bay fishing, to generate more economic growth for the region. In Sanya city, this shift is already happening, with the city’s fishing boats all relocated to a port in Yazhou.

The South China Sea Museum was a big part of the economic transition plans, with Hainan’s tourism authority announcing that the museum had been approved as a “national 4A tourist attraction.”

This transition, however, is not without complications. Shi, who is now retired in Sanya, said, “Our children have no way to go to sea, so they work for tourism companies and earn 3,000 RMB ($460) a month, and these companies do not hire people in their 40s and 50s.”

Li is one of the few captains in Tanmen who still does distant-water fishing, and he insists on going with his wooden boat. The government has put pressure on him several times since 2019, asking him to cooperate with the “full demolition of the old.”

“In the past, these 100-ton wooden boats could run to Nansha and Malaysia, but now they say that wooden boats are not compliant and do not meet safety standards, and they need iron boats of 500 tons or more to do it,” he said indignantly. “It’s all fake!”

Whether the option is catering or tourism, Li is not confident that he can do any of these better than fishing. “At the coast, what can you do if you don’t catch fish?” – Rappler.com

This story is part of Oceans Inc.’s “Fishers on the Frontlines,” which explores how fisherfolk across the South China Sea have been impacted by illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing and the ongoing maritime territorial dispute.

Oceans Inc. is a collaborative investigation by the Environmental Reporting Collective, involving 23 journalists from over a dozen countries looking into IUU fishing. Follow the full investigation at www.oceansinc.earth.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[DOCUMENTARY] Our 15 kilometers: Small fishers fear losing municipal waters to big operators](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/our-15-kilometers-iuu-fishing-docu.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=279px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.