SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Most of 23-year-old Anjeneth Nocete’s life is connected to the sea.

She lives in Navotas, where one of the Philippines’ major fish ports is located. Her husband used to be a fisherman since his teenage years before transferring to a job that involves harvesting tahong (mussels).

Nocete herself worked for at least six years processing freshly caught fish brought to the port. She would check each fish, assess its quality, and place them in appropriate containers depending on its size.

The things that come with working in the fishing industry have inevitably spilled into her household. Fish has become such a staple in their dining table that a meal is not complete without it, even if Nocete has to stretch P150 to P200 ($3 to $4) a day for 10 people.

“Madalas talagang isda ang binibili rin namin kasi paborito talaga ng anak ko,” she told Rappler. “Iyon lang ang alam niyang ulam.”

(We really usually buy fish because it’s my child’s favorite. That’s the only food he likes.)

Tips when buying fish

Nocete’s family is just one of the many Filipino families who consider fish among their main sources of sustenance.

With the Philippines being an archipelago, good quality fish is to be expected. It’s not unusual to find fish ports all over the country, with coastal areas getting the best ones.

Philippine waters, after all, have 3,369 of the known fish species in the world. (READ: Get to know your fishes: 5 common species found in Philippine waters)

Still, buying fish can be tricky, especially for those in Metro Manila. According to Sharwin Tee, chef and author of the recently published cookbook The Gospel of Food, storage and transport are huge factors when it comes to the freshness of fish.

“Since we have warm weather throughout the year, it’s critical that the fish are stored well in ice as soon as they are caught and they are transported as quickly as possible to the market,” he told Rappler.

At local markets, where there is no air-conditioning, keeping the fish alive or kept chilled in ice are important.

But what else should people look out for when buying fish from the market?

No ‘fishy’ smell

People often attribute “amoy malansa” to fish. But a good quality fish should not smell like that, according to Tee.

“This may sound counterintuitive, but the freshest fish don’t smell ‘fishy,'” he explained. “Fresh fish should smell like the sea.”

Clear eyes

Another thing that one should check is the eyes. Tee said the eyes of the fish should be clear.

Plump to the touch

Don’t hesitate to use your hands when checking the quality of the fish you plan to buy. Touch it and try to press the fish meat, Tee said.

“The meat should still be plump and slightly bouncy,” he added.

While these tips are very important, Tee said a key ingredient in making sure you get the good, quality fish is to build a good relationship with your fish seller, also called a fishmonger. After all, they are more knowledgeable about the quality of the fish they sell and the fishing industry as a whole.

“That way, you trust their judgment and their recommendations,” he said. “If you have a suki, they will be able to help you find not only the right fish for the right dish but also the freshest one.”

Nocete knows all these too well, having worked alongside fishmongers herself. She uses this knowledge when buying for the family. Once or twice a week, she would go to the market, careful to check the gills (hasang) and scale (kaliskis).

“Alam na alam ko kung ano ang magagandang isda, kasi iyan ang trabaho ko,” Nocete said. (I know what a good quality fish is because that’s my job.)

Still, sometimes it’s inevitable that they’d get fish of subpar quality. Sometimes they have to be content with buying frozen fish or those not fresh at all, especially if they arrive too late at the market or do not have any budget.

“Minsan frozen, minsan makati na sa dila, kaya kadalasan sumasakit tiyan din namin,” she said. (Sometimes they’re frozen, sometimes they’re already itchy on the tongue, so we often get stomachache.)

Know your seafood

Beyond quality and safety concerns, consumers are increasingly looking to make responsible choices with their purchasing decisions. Responsible seafood consumers avoid buying protected species like Napoleon wrasse (mameng), sawfishes, sea turtles, marine mammals, some rays, some sharks, giant clams, and some other shellfishes, among others.

These species are categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), and the local government as endangered or threatened, meaning they are in decline and may be in danger of extinction. Their sale and purchase is illegal and should be reported to BFAR or the local authorities.

Responsible consumers also refrain from buying breeders, spawners, and juveniles of fish because the excessive harvesting of fish at these critical life stages reduces the number of adults in the wild that can reproduce, resulting in fewer fish available in the future.

Philippine law prohibits the capture of mother bangus (sabalo) and other breeders and spawners, as well as milkfish fry (kawag-kawag) and juveniles of other species. To guide fishers, sellers, and consumers, size limits are set or recommended for certain marine products.

For mudcrab (alimango), for example, the BFAR has set a minimum size limit of 10 centimeters (cm). For blue swimming crab (alimasag), a minimum size limit of 11.5 centimeters (cm) is recommended, based on scientific assessments supported by the Fish Right Program.

Fish Right is a partnership between the BFAR and the US Agency for International Development or USAID to improve marine biodiversity and the fisheries sector in South Negros, Visayan Sea, and the Calamian Islands in Palawan.

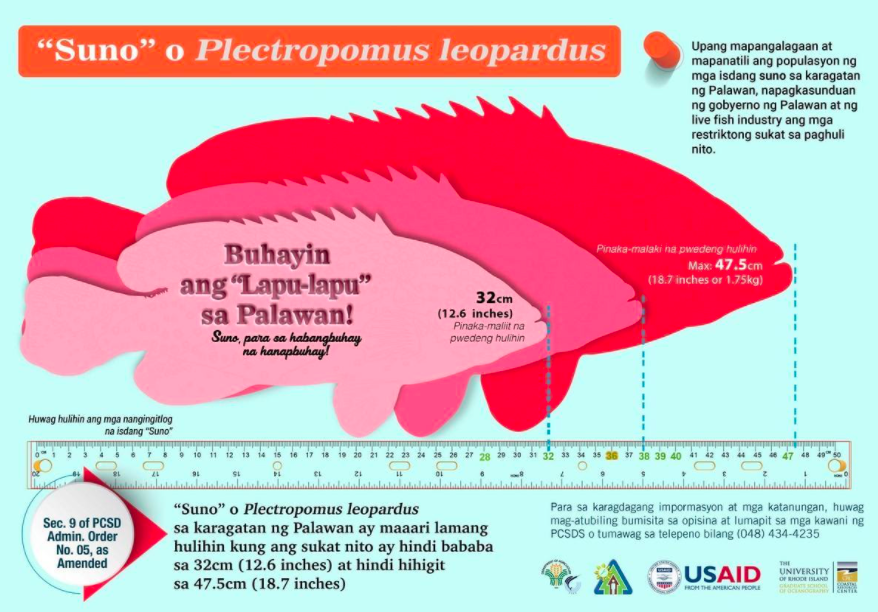

In Palawan, Fish Right assisted the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD) in determining the appropriate size limits for the Leopard coral trout or suno (Plectropomus leopardus). The PCSD has since adopted a regulation that prohibits taking fish of this species that measure less than 32 cm and more than 47.5 cm in length.

Threat to food security

Responsible consumers are also increasingly demanding assurance that the seafood products they buy do not come from illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing or overfished fishing grounds.

IUU fishing, as defined by the BFAR, ranges from “unlawful activities of domestic small-scale fishing to more complex operations carried out by industrial fishing fleets.”

It is a key driver of overfishing as it catches fish at a rate that leads to a rapid decrease in fish populations and often involves gears and practices that damage fish habitats and capture fish before they have matured and reproduced. This impairs the fish stocks’ ability to replenish themselves, resulting in diminishing fish supply and higher prices.

In countries like the Philippines where fish is a major source of protein and livelihood, IUU fishing poses a serious threat to food security and socioeconomic stability.

Nocete’s family is just one of the thousands of Filipino families at the frontline of this threat. Back when he was a fisherman, Nocete’s husband would often go home empty-handed every time he and his crew encountered illegal fishers around the area where they fished.

“Kapag nangyayari iyon, talagang walang isda silang mahuhuli, kaya umuuwi na lamang sila. Ibig sabihin walang kita, kaya wala rin kaming budget,” Nocete said. “Nahihirapan rin kami.”

(Whenever that happened, they wouldn’t have any catch, so he’d just go home. That meant no income, so we wouldn’t have a budget [for the week]. It was hard for us.)

The Pambansang Lakas ng Kilusang Mamamalakaya ng Pilipinas (Pamalakaya), a national federation of fisherfolk organizations, points to commercial fishing as the main culprit of overfishing and stock depletion in municipal waters.

Municipal waters are bodies of water within the municipality that are not within protected areas covered by the National Integrated Protected Areas System. They include marine waters from the general coastline, including offshore islands and 15 kilometers from such coastline.

The law reserves these waters for municipal fishing, which means “fishing using fishing vessels of less than 3 gross tons, or fishing not requiring the use of fishing vessels.”

“Dahil sa malalaking komersiyal na pangisda na nagsasagawa ng ilegal, walang limitasyon, at walang regulasyong pangingisda, nasisira at nauubos ang mga isda at yamang-dagat na para sana sa mga maliliit na mangingisda,” Fernando Hicap, chairman of Pamalakaya, told Rappler.

(Because of big commercial vessels illegally fishing without limits and in an unregulated manner, small fisherfolk are left with no fish to catch.)

In 2019, illegal fishing accounted for about 516,000 to 766,000 metric tons of fish caught in the Philippines valued at between P41.8 billion and P62.6 billion, according to a study conducted by Fish Right.

The 2015 amendment to the Philippine Fisheries Code, called An Act to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate IUU Fishing, increased the penalties for IUU fishing to ensure they serve their deterrence purpose.

Pamalakaya said the government should prioritize enforcement against big, commercial vessels illegally fishing in municipal waters. It should also strengthen and give teeth to policies against foreign vessels that trample on the rights of small Filipino fisherfolk, including those in the West Philippine Sea.

“Ang mga dambuhalang barkong pangisda na pag-aari ng malalaking negosyante at pulitiko ang talagang gumagawa ng ilegal at walang pakundangang pangingisda sa paghahabol ng malaking kita,” Hicap said.

(It’s the big vessels owned by big businessmen and politicians that are behind illegal fishing because they want to earn big.)

Sustainable seafood

Tee, for his part, said he preferred to source fish from regulated and sustainable fishing, and expressed hope that restaurants would follow suit. Encouraging the use of local and sustainable seafood is important as it further influences the public to do the same, he said.

Determining if seafood comes from sustainable fishing is not a straightforward affair, however, and without some form of auditable marking on the product itself or its packaging, there is no way for an ordinary consumer to tell if seafood is “sustainable” and where it comes from solely by looking at it.

But there is a growing movement toward full traceability of seafood supply chains. In markets like the United States (US), the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK), where there is a fairly established demand for responsibly sourced seafood, more and more food retailers and restaurant chains are requiring end-to-end traceability to ensure that IUU seafood products do not enter their supply chains.

The movement has been aided considerably by government programs such as the EU‘s (and UK‘s) catch certificate scheme and the US Seafood Import Monitoring Program. These programs aim to provide traceability and prevent the import of IUU seafood into their respective markets through tracking, reporting, and keeping records of the seafood product “from bait to plate.”

Catch documentation in the Philippines is still largely about compliance with the traceability requirements of importing countries, but even here, there is an emerging demand for sustainable seafood, driven largely by international hotel groups aiming to implement sustainability policies and commitments across their global operations.

BFAR has piloted and plans to scale up the implementation of an electronic catch documentation and traceability system or the eCDTS primarily for traceability purposes, but also to guide measures to enhance fisheries sustainability and productivity – a development that should be welcome to Nocete, Hicap, Tee, and their respective sectors.

“It’s been made apparent for so many years that overfishing is causing the extinction of so much of our marine life, and that directly affects environmental health, which affects human lives as well. It’s only responsible that we begin doing what we can to save the planet for the future generation,” Tee said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.