The Philippines' national flower is also the name of a shop in Japan's old capital, selling elegant bags and hats made of Philippine fibers and assembled by Filipino workers

KYOTO, Japan – In this city of everything tasteful and pretty, tourists would notice the boutique among the little quaint shops for the stylish bags and hats it displays.

If you were from the Philippines, though, then you’d be drawn to the shop just by its name: Sampaguita.

Unmistakably Filipino. Must be owned by a Filipino. I told myself that the first time I passed by it on Aburayacho street.

Thanks to Japanese friends, I quickly learned that the shop bearing the name of the Philippines’ national flower, selling bags and accessories made of natural fibers, is owned not by my kababayan…but theirs.

Specifically, it is owned by a Japanese, who was working on a PhD in development economics at the Kyoto University, did some graduate research at the University of the Philippines (UP), immersed himself in factories in Marikina, went back to Osaka to work in a private research institute, then decided he’d rather be a businessman.

Shingo Fukuda is not even 40, but the Sampaguita bags, hats, and accessories he started producing less than 4 years ago are making a mark in the fashion consciousness of both residents and tourists in Japan.

Sampaguita products are distributed by 30 retailers all over Japan, and are on display in the Takashimaya malls – the equivalent, he says, of Rustan’s in the Philippines.

In 2009, Fukuda was based at UP’s Asian Center, curious about “how globalization was affecting 3rd-world countries.”

“I did an investigation into Marikina shoes,” he said. “They were famous, of high quality. Filipinos knew, but didn’t buy a lot. Why?”

He points out that Marikina used to export shoes, but when the WTO and globalization happened in 1995, “they (manufacturers) stopped, while cheap shoes started coming in [from other countries], including smuggled ones.”

“How did they survive?” – that was his research question. He became part of the answer a few years later when he rolled out Sampaguita in February 2014.

Fukuda went back to the manufacturers in Marikina, proposing that they make bags and shoes for him, based on what the Japanese market was ready for.

“The Japanese were looking for something new,” he said, recounting that, at the time,

ata bags from Bali, Indonesia, were selling well, being paired with the

yukata.

“Takashimaya expects buntal to be as popular,” Fukuda said.

Buntal bags go superbly with kimonos. And kimonos, as any tourist knows, are a big thing in Kyoto – you rent them and walk the streets of Gion for a full experience of the old capital.

Sampaguita has since expanded the kinds of native fibers it uses, and deals with more manufacturers outside of Metro Manila, even as far as the Visayas, in the Philippines.

“The main risk in the fashion business is that competitors can easily copy your products,” Fukuda said.

He is confident, though, of what will keep Sampaguita bags and accessories stand out: the high quality of materials, the meticulous work, and the attention to detail that the Japanese are known for.

The designs of Sampaguita products are made by the Japanese. While the fibers are sourced from the Philippines, the genuine leather, quality hardware, and silk lining used are from Japan.

The competitors who copy, meanwhile, only have synthetic leather, poor hardware, and cheap lining, Fukuda says.

The personal touch matters too. Fukuda visits the factories often, inspecting the products carefully, and encouraging the factory owners to provide workers with continuous training to improve their craftsmanship.

In some villages in the Visayas, he says proudly, some fishermen have changed occupation to make bags for Sampaguita’s suppliers.

“The workers are paid according to how many pieces they can process,” he observed, so some of them turn in shoddy work in the rush to produce more.

“It’s the factory owners that have to motivate the workers. I tell them I’m willing to pay more, or give bonuses, if they work harder.”

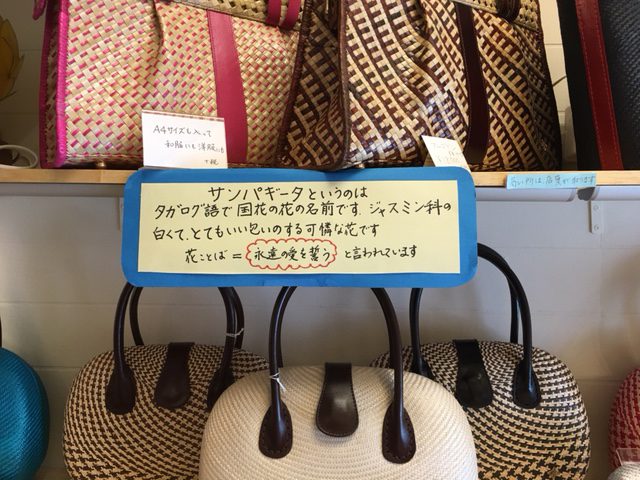

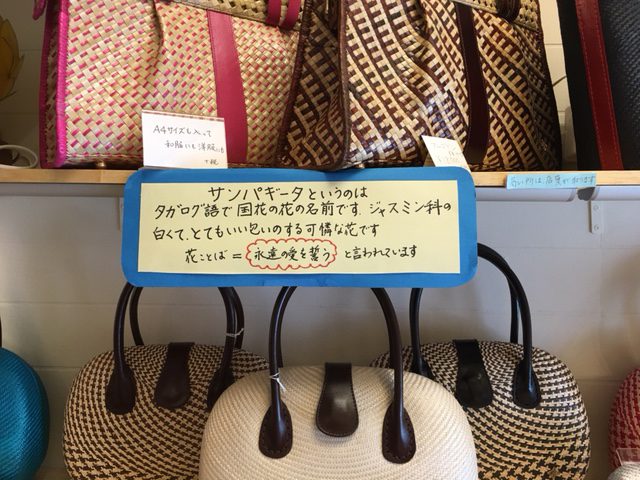

Customers in Kyoto, of course, ask him what the shop’s name means. He has a note, in kanji, posted with the product displays. It roughly translates: “Sampaguita, a Tagalog word, is the Philippine national flower. It belongs to the jasmine group. The tiny white flower smells very good.”

Why name your shop after the Philippine jasmine to begin with? “I was impressed by the meaning of the word, how it expresses eternal love,” Fukuda said.

The legend goes that the son and the daughter of two warring chieftains in Manila fell in love and secretly met at the end of the bamboo fence that separated their villages. War between the fathers’ men led to the death of the son, and the death of the son led to the daughter falling ill and eventually dying.

The lovers were buried where they used to secretly meet. Since then, villagers would hear the wind in that direction seemingly whispering, “

Sumpa kita… sumpa kita (You are my promise… you are my vow).” And from that spot too grew a shrub that bore, every summer, tiny, fragrant, white flowers.

So, yes, Sampaguita, the Kyoto shop, is Japanese – Japanese embracing what’s lovely and enchanting about the Philippines. –

Rappler.com

![[OPINION] Why is Japan Home Centre accepting sibuyas as payment?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/02/japan-home-center-february-3-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=188px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.