SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines–Wearing a white polo-barong, grey slacks, and black sneakers, Dr. Onofre Pagsanghan, 86, looks like he’s going to a funeral. His balding white hair is neatly-combed, although in his age, there’s more scalp than hair to be seen. His face is outlined by deep creases beginning from the sides of his nose tracing down to corners of his thin lips, and continues on both sides down to his chin like the lines you would see on a marionette doll. On his face sits a pair of thick-rimmed glasses covering his deep-set eyes that are a subtle shade of blue. His lean arms are peppered with blemishes leading to his bony hands covered in a strange white powder. “Chalk dust,” he apologizes. Nearby, a metal walker stands.

One wouldn’t probably take notice, but Sir Pagsi, as he is fondly called by his students and colleagues, has been teaching freshman high-school students in the Ateneo de Manila University for the past 62 years. He has no plans of retiring, and – up until an accident that led him to use the metal walker one year ago – hasn’t missed a single school day in the past half-century including during his wedding day. He still wakes up at 5 in the morning to go to school, and still writes his exams on Manila paper.

“I know of no other profession apart from teaching that gives so much for so little.” He doesn’t keep count, but the English and Filipino teacher has taught thousands of students over the years, some of whom are the sons and grandsons of his first students.

To celebrate Teachers’ Month, Pagsanghan was the special guest during the opening of The Many Faces of the Teacher exhibit at SM North EDSA in Quezon City on September 16. As cameras clicked, he spoke in front of a small crowd of teachers and students.

And when Pagsanghan speaks, there is a comforting and mesmerizing quality to his voice so used to speaking to a class of 40 teenage boys about Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” or a lecture hall of some 4,000 public schoolteachers about teaching as a vocation.

Coming from a poor family in an impoverished area near Tondo, Manila, Pagsanghan says, “poor boys like me dreamt about and hungered for the quality education that the more expensive schools gave. It was my inay who first lit the flame of that hungry dream in my life.” Pagsanghan recalls, “When I was a little boy, my inay would clasp my forehead and say, ‘Anak, wala tayong panlaban sa ating kahirapan kundi ang utak mo’ [Son, only with your intellect can we overcome our poverty.] I caught the fire in her voice and the dream in her eyes. I learned the first and most important lesson in my life – to dare dream.”

A full scholar, Pagsanghan graduated from the Ateneo High School in 1947 before finishing college in the same university in 1951, majoring in Education. After receiving his diploma, Onofre Pagsanghan went straight to teaching.

‘Paid to sleep’

He recalls his first experience when he applied for the job. Frail and weighing in at less than a hundred pounds, he approached the principal back then, an American Jesuit, who agreed to accept Pagsanghan on one condition: that everyday, after lunch, he would go up to one of the high school’s buildings, enter an unused room, and sleep. “I was probably the only person in the world who was paid to sleep,” Pagsanghan says, “They thought I wouldn’t last.” They were, of course, very wrong.

It was in the Ateneo that Pagsanghan was to find his home for the rest of his life, teaching English and Filipino to freshmen students. “When you’re teaching,” he says, “the most important question isn’t the what, when, where, or how. It’s the why.”

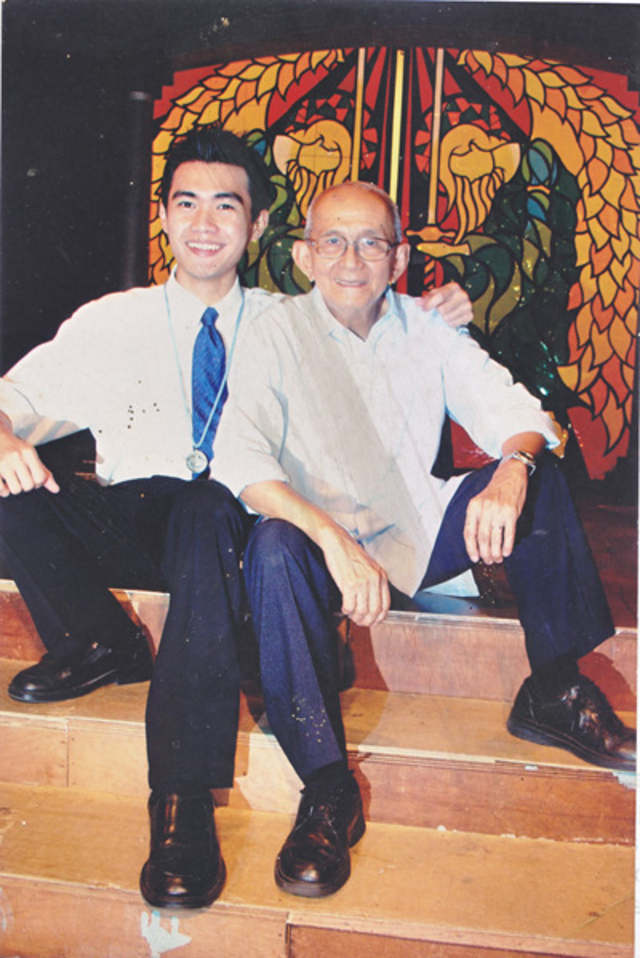

In 1956, Pagsanghan began teaching theater as moderator of the Ateneo High School Dramatics Society. The group later changed its name to Dulaang Sibol and has since been, as critic Bien Lumbera calls it, “a seminal force in the development of Philippine playwriting.” Pagsanghan’s work as managing director of Dulaang Sibol attracted national recognition from critics and ordinary theatergoers alike. With his students, he put up one-act plays like Paul Dumol’s “Ang Paglilitis ni Mang Serapio,” and co-authored musicals such as “Adarna,” “Sa Kaharian ng Araw,” and his transplantation of Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt’s “The Fantasticks, Sinta.”

To date, countless awards have been given to Pagsanghan in recognition of his efforts in molding young students’ minds and spreading his passion for teaching throughout the country. Upon the mention of his name, he becomes noticeably uncomfortable, saying, “Honestly, at 86, the awards, certificates, and plaques are not that important.”

Pagsanghan goes back to his inspiration, “My inay taught me that it was useless to dream, if I was not willing to pay the price of my dream.” When asked who his greatest teacher was, he recalls American Jesuit John P. Delaney, S.J. He was the principal of the Ateneo High School when Pagsanghan was in his senior year, and Father Delaney was later assigned chaplain at the University of the Philippines. “For him, a saint is somebody who wants the hardest and the best. And looking back at my life now, he was right, because the hardest is almost always the best, and the best is almost always the hardest.”

More than 20 years past retirement age, Onofre Pagsanghan sees no end to his life, teaching students to dream as he was once told. Nearly a year ago, he suffered an accident that left his left leg in a cast and him missing class for a month and a half to recuperate and undergo rehabilitation. It was the longest he’s ever missed school. But now that he’s back, metal walker in hand, it’s like he never left – albeit he walks a little bit slower now.

“It’s like in that story of the violinist Itzhak Perlman,” he begins to narrate. In the narrative, the Israeli-American violinist breaks a string in the middle of a concert, but continues playing until the very end. “He says it’s the artist’s job to play with all that he’s got and when that’s no longer possible, to play with what he has left,” Pagsanghan paraphrases. “With what I have left,” he trails off. “I have a lot more left.”

When asked why he still wakes up at 5 in the morning to prepare for class, he shrugs his shoulders and says, “I have one life. What would I be able to give with one life? I try to give it meaning. Love your calling with passion. It’s the meaning of your life. This is the meaning of my life. My being a teacher is the meaning of my life.”-Rappler.com

Here’s a documentary about Dr. Onofre Pagsanghan:

The Many Faces of the Teacher was presented by the Bato Balani Foundation, Diwa Learning Systems, and the First Asia Institute of Technology and Humanities (FAITH).

Peter Imbong is a full-time freelance writer, sometimes a stylist, and on some strange nights, a host. After starting his career in a business magazine, he now writes about lifestyle, entertainment, fashion, and profiles of different personalities. Check out his blog, Peter Tries to Write.

Peter Imbong is a full-time freelance writer, sometimes a stylist, and on some strange nights, a host. After starting his career in a business magazine, he now writes about lifestyle, entertainment, fashion, and profiles of different personalities. Check out his blog, Peter Tries to Write.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.