SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

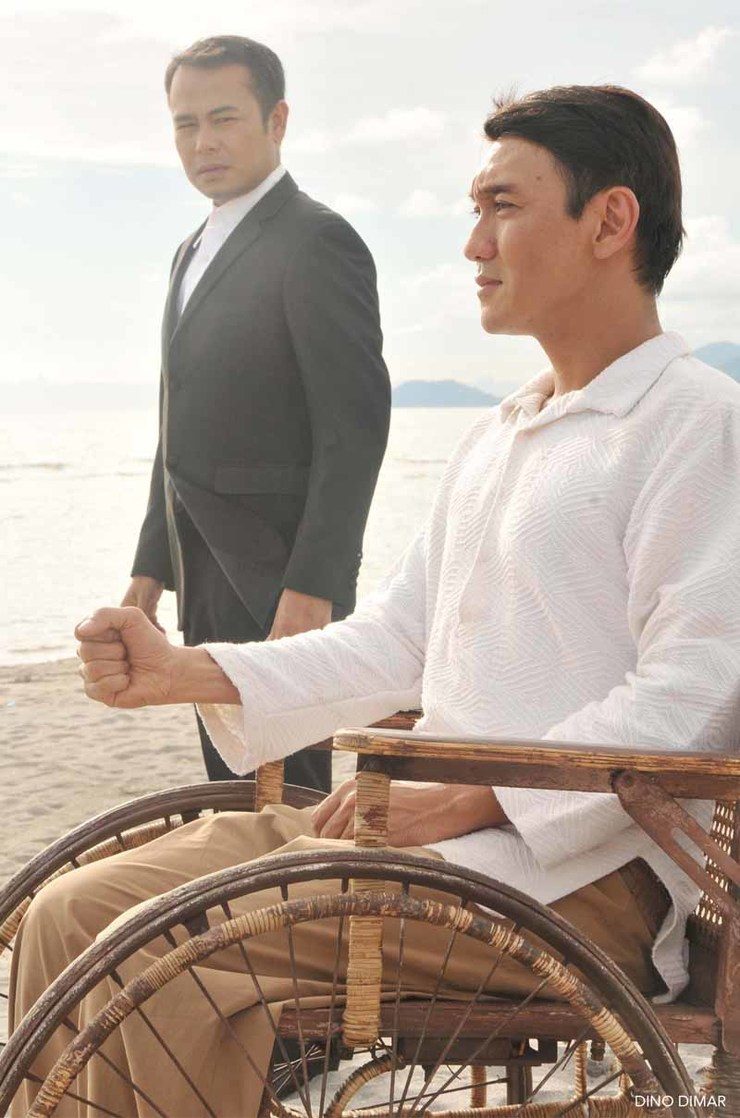

On a wide expanse of a tropical beach that invites the youthful to frolic, sprint, and swim, a crippled polio survivor sits on a wheelchair mired in the sand, unable to feel the warm gentle waves lapping at his feet.

In this landscape that inspires elation and tranquility, he is a vanquished revolutionary with a mind full of crackling embers. He stares at the distance, not to enjoy the beauty that surrounds him, but to long for the motherland from which he was sundered. This paradise, much like his home but not quite, is his exile.

An author, a statesman, and a freedom fighter – that man is Apolinario Mabini, best known as the Philippine revolution’s sublime paralytic. And this is the story of his exile in Guam and his return.

Librettist Floy Quintos, director Dexter M. Santos, and composer Krina Cayabyab collaborate to reveal the little known story of this hero’s exile and subsequent return in Dulaang UP’s musical, Ang Huling Lagda ni Apolinario Mabini (The Final Signature of Apolinario Mabini).

The show will run from October 1 to 19 at the Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero Theater, second floor of Palma Hall, University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman. It is a one-act play set to run for about an hour and 30 minutes. Tickets are P350.

Headlining the cast are Roeder Camañag in the titular role of Mabini, Banaue Miclat, Jean Judith Javier, Nazer Salcedo, Al Gatmaitan, Leo Rialp, and Poppert Bernadas. The ensemble includes Ralph Oliva, Chase Salazar, Adrian Reyes, Arion Sanchez, Bym Buhain, Edmundo Abad, Jr., Ralph Perez, Ross Pesigan, Roco Sanchez, Rence Aviles, Jon Abella, and Vincent Pajara.

The artistic staff includes lighting designer John Batalla, set designer Ohm David, costume designer Darwin Desoacido, dramaturg Marvin Olaes, and assistant choreographer Stephen Viñas.

Secret life

The play recounts the little known final episode of Mabini’s life that begins with his forced exile to Guam in 1901with other captured revolutionaries.

Though he had contracted polio and subsequently lost the use of his legs 6 years prior, Mabini was nonetheless deemed a threat by American occupiers.

They had recognized his leadership and his intellect during the failed peace negotiations of 1899, wherein Mabini represented Philippine revolutionary government. Even after his capture and incarceration on December 10, 1899, Mabini was asking his fellow Filipinos to rise up against the American occupiers.

Wanting to avoid making another martyr for the revolution as the Spanish had done by executing Philippine National Hero Jose Rizal, future US president and then governor-general of the Philippines William Howard Taft cunningly exiled the captured freedom fighters to Guam instead.

Mabini, along with General Artemio Ricarte, became the last of the exiles to return to the Philippines in February 1903. Unlike Ricarte who refused to sign the oath of allegiance, Mabini did on February 26, 1903 – this, according to American historians of the time.

Nonetheless, the incorrigible Mabini resumed agitating for independence soon after, much to the chagrin of the Americans. Mabini died two months later from cholera on May 13, 1903 at just age 38.

The son of a market vendor and an illiterate peasant, who paid for his own law education through teaching, as well as a Free Mason and a revolutionary who was highly critical of his own allegedly corrupt and fratricidal leader Emilio Aguinaldo, Mabini has since become the subject of several works of art.

The most notable of which is Agnes Locsin’s La Revolucion Filipina where the paralytic Mabini becomes protagonist of this dance interpretation of his scathing memoir of the same name.

Now, on the 150th anniversary of Mabini’s birth, Quintos, Santos, and Cayabyab add a new dimension to his portrayal that promises to further deepen the understanding and appreciation of Mabini’s heroism and humanity.

Glimpses of history

At a recent press preview at the UP Faculty Center’s Teatro Hermogenes Ylagan, Quintos presented a few select scenes from the upcoming musical.

Besides the historical roles of Mabini (Camañag), Ricarte (Gatmaitan), Aguinaldo (Salcedo), and Taft (Rialp), Quintos chose to add the fictional character of Salud (Miclat), a nurse who tends to the sickly Mabini. Miclat’s sweet voice adds some contrast to most male cast.

Santos noted that this play is in complete contrast to his previous works such as Maxie the Musicale, that rely on lavish productions and gaiety to win over audiences, Mabini is a stark and somber historical narrative. The acting and the singing shine in naked glory.

He explains, “No fancy production numbers. No complicated choreography. It’s really more plot driven and character driven. That’s why it’s very very exciting for me.”

Most striking was Camañag’s performance, especially his movement. Confined to a wheelchair, the actor nonetheless used his body language, most especially the constrained movements of his hands and the distant stare of his eyes, to communicate the conflict and turmoil within his character’s mind.

He explains, “I had a grandfather who became a paralytic. I could see how his mind ran with the many things happening in his eyes. Because he could not move his body, his mind was running all the time.”

At the preview, Cayabyab herself performed the music with a keyboard. However, she noted that during actual performances, live music will be provided by a piano, cello, viola, and two violins.

After witnessing select scenes presented that night, it became clear that Cayabyab’s works demanded only the very best from the cast. Her songs were characterized by wide melody changes and quite a number of tempo changes.

There were few if any hooks. Instead of banking on the usual ear-candy conventions that appease audiences and their pop expectations, Cayabyab’s compositions were progressive showcases of virtuosity that seem to appeal more to fellow musicians and theater cognoscenti.

Camañag himself confessed, “As an artist, you are challenged to do your homework. She’s a perfectionist in a good way because she’s very strict and very particular with the tempo. If you come to the rehearsals unprepared, it’s you who will feel embarrassed for yourself. So it’s nice to be working with her.”

Quintos’ lyrics also made no compromises. It seemed that the music was made to fit his words instead of the words being made to fit the music. Miclat attested, “Sir Floy [Quitos]’s language is so beautiful. It flows into the song. And when you already know the music, everything flows.”

Cayabyab noted that her compositions referenced the music of the play’s milieu—the era when the Spanish-influenced sarsuwela (zarzuela) began to be superseded by American-influenced bodabil (vaudeville).

She revealed, “Sir Dexter [Santos] and Sir Floy [Quintos] told me that they envisioned a bit of a way between classical and twentiethcentury contemporary music and the broadway musicals. Our peg was to find that middle point.”

Quintos added, “On the second number we showed with Al [Gatmaitan], there’s a little bit of Spanish music, flamenco, since the revolutionaries were romantic. The revolutionaries would have been familiar with this. But otherwise with all the other numbers it’s still Krina [Cayabyab]’s interpretation.”

More than just entertaining audiences with music, Quintos’ objective is the revival of the hero’s ideals as revealed in his El Verdadero Decalogo (The True Decalogue), a 10-point code of ethics that was part of the constitutional program Mabini himself authored.

So adamant is Quintos about its revival that he required his cast to know it by heart. He stated, “If there is one thing that we really hope this musical can do, it is to awaken interest in Mabini’s True Decalogue, which is no longer taught in Philippine schools. Mabini’s greatest work was designed to be a code of personhood for the Filipinos of the revolution. Reading it again, I could not help but think that this was the very moral compass that young Filipinos so lack in these times.” – Rappler.com

For tickets, sponsorships and show buying inquiries, call 926-1349, 433-7840, 981-8500 local 2449 or email dulaangupmarketing@gmail.com.

Writer, graphic designer, and business owner Rome Jorge is passionate about the arts. Formerly the Editor-in-Chief of asianTraveler Magazine, Lifestyle Editor of The Manila Times, and cover story writer for MEGA and Lifestyle Asia Magazines,Rome Jorge has also covered terror attacks, military mutinies, mass demonstrations as well as Reproductive Health, gender equality, climate change, HIV/AIDS and other important issues. He is also the proprietor of Strawberry Jams Music Studio.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[In This Economy] A counter-rejoinder in the economic charter change debate](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/TL-counter-rejoinder-apr-20-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=267px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Vantage Point] Joey Salceda says 8% GDP growth attainable](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-salceda-gdp-growth-04192024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[ANALYSIS] A new advocacy in race to financial literacy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/advocacy-race-financial-literacy-April-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.