SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Necrological services were held at the Cultural Center of the Philippines last Sunday, December 21, for National Artist Abdulmari Asia Imao, who died December 16 at the age of 78.

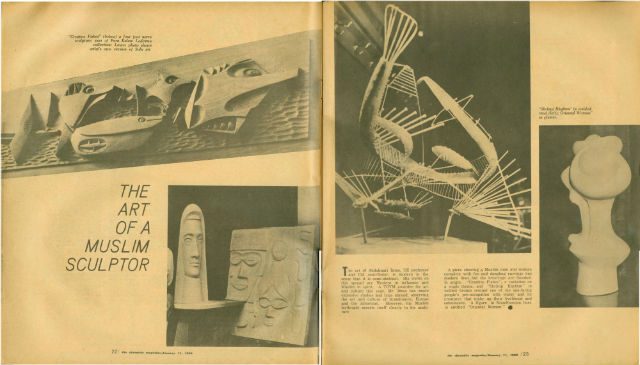

Well known for using the sarimanok bird motif in his paintings and sculptures, it was fitting that the service was visually dominated by hundreds of smaller sarimanoks coming down from the ceiling of the CCP’s Main Theater. But I always thought that there was more to Mr. Imao’s art than those motifs that have made him famous.

I had the good fortune to interview Mr. Imao in 2013. And when I visited his house in Marikina, I was surprised to see a number of Christian artifacts (antique santos, crucifixes, and altars) share space with family mementos like grandson Kyle Imao’s Junior Masterchef trophy.

We had coffee on a table once owned by Maximo Viola, and Mr. Imao explained that he believed Jose Rizal wrote parts of his Noli Me Tangere on it. Every part of that house was a testament to Philippine cultural history.

It was then that I realized that while Mr. Imao’s imagery – the sarimanoks, the nagas, the vinta-like colors and clear lines – reflected his heritage, he was completely aware of how his own practice fit in the larger discussion of Philippine art. I felt that Mr. Imao was consciously attempting to articulate a Philippine identity through his work.

Not many people are aware of how ingrained Mr. Imao’s work is in methodical research. An academic who has pursued post-graduate studies at the University of Kansas, the Rhode Island School of Design, and Columbia University, Mr. Imao spoke 12 dialects and was once one of the country’s Commissioner of National Languages.

So while his work is legitimately rooted in his experience as a Filipino Muslim, it is also borne of an intense study of the aesthetics of traditional Maranao and Tausug folk art. The motifs he uses are all consistently recurring in the traditional indigenous woodcarvings of Muslim Mindanao. The medium of his sculptures – brass – is formed from indigenous pre-colonial metalworking techniques. The genius of Mr. Imao is in his ability to bring everything together in clean, Modernist visuals.

This is why his selection as National Artist was significant. As the first Filipino Muslim National Artist, it was a statement about the importance of the Islamic tradition in molding our sense of cultural identity. And the suspicion that it was somehow a political move is a misguided notion that not only fails to understand the process of nominating a National Artist, but is also ignorant of the entirety of Mr. Imao’s artistic and academic contributions.

Through his art, it would seem that his greatest achievement was to bring indigenous folk art into the national cultural consciousness. The Islamic motifs he used brought interest in the art forms they’re derived from. His works serve to bridge Philippine Islamic culture with the rest of the country. And since these motifs also recur throughout South and Southeast Asia, Imao’s works also remind us of our own Asian roots and connections.

There is no doubt in my mind that Mr. Imao’s artistic achievements are considerable. But in knowing him, I have to say that he was also a very decent human being. The family honor wall in his house displays keepsakes of the achievements of his children and grandchildren. He honored his late wife, Grace, by lovingly creating an altar sculpture of wood, brass, and glass. He spoke of himself modestly, and had an unwavering sense of humor.

His sons Toym and Sajid continue his legacy with dynamic art careers of their own – with Toym recently garnering attention for his Voltes V-inspired installation at steps of UP’s Palma Hall, entitled Last, Lost, Lust for Four Episodes.

It’s a sad moment for the art community, but it’s comforting to know that Mr. Imao’s efforts have paved the way for a new appreciation and understanding of Islamic culture in the Philippines and its role in giving us a sense of identity. – Rappler.com

Duffie Hufana Osental is a Palanca Award-winning art writer and editor. He is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Art+ (Contemporary Art Philippines) Magazine.

Duffie Hufana Osental is a Palanca Award-winning art writer and editor. He is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Art+ (Contemporary Art Philippines) Magazine.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.