SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Few places exemplify the Filipino’s contradictory attitudes towards, well, just about everything, the way Quiapo does.

Outside the Quiapo church, street vendors sell images of the Virgin Mary along with mystery herbs meant to induce a woman’s period (presumably after having had unprotected sex).

In those same stalls, rosaries compete for space with anting-antings – baubles that predate our Catholic history. And both the church itself and nearby motels enjoy a steady stream of faithful clients.

While most people would see contradiction and chaos in our streets, artist Auggie Fontanilla takes inspiration from the sturm and drang of contemporary street culture.

“Dun ako kumukuha ng energy,” Fontanilla says. “People would say, ‘Ayoko dito, magulo dito.’ But to me, masaya ako. There’s so much happening. May chaos at kulay. I can use anything (from the streets for my art). That’s where I get my inspiration.”

‘Kristo ng Lansangan’

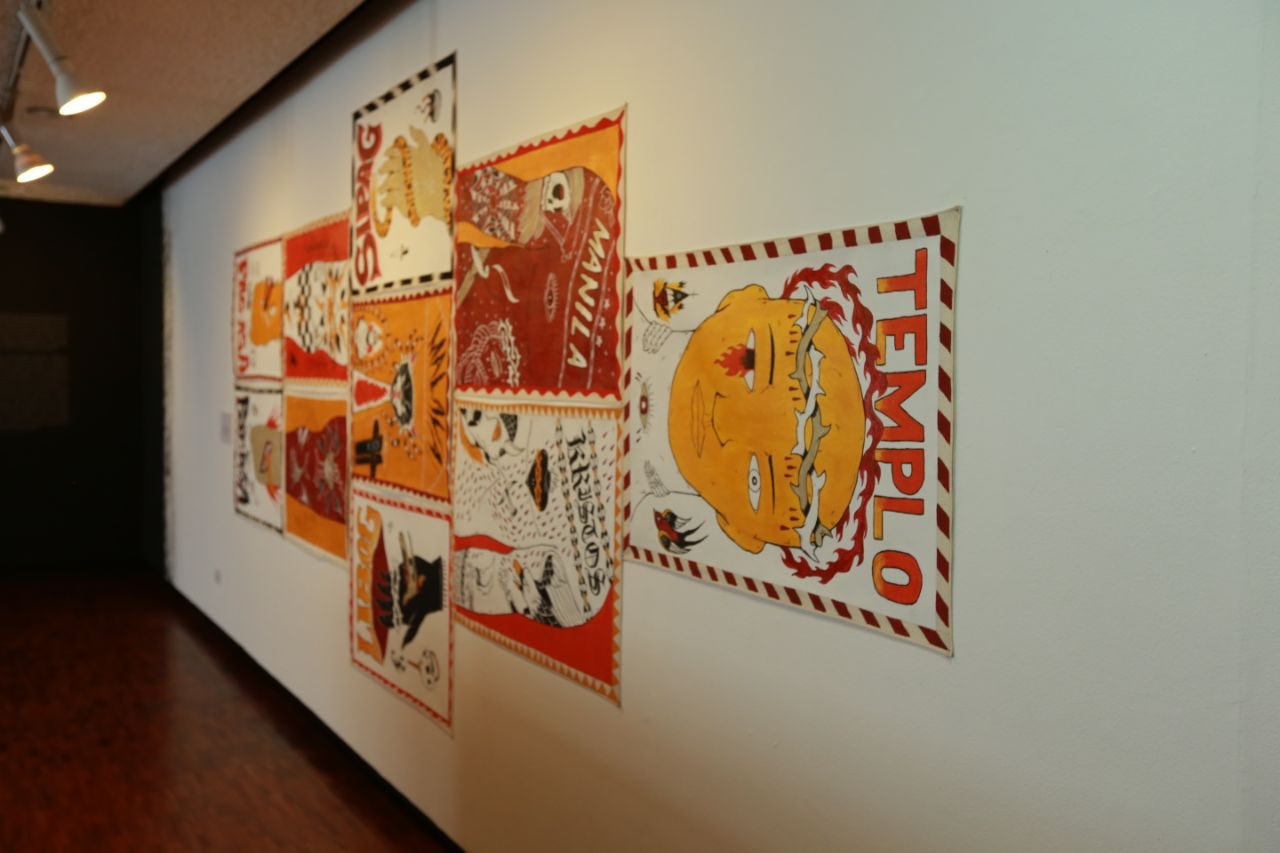

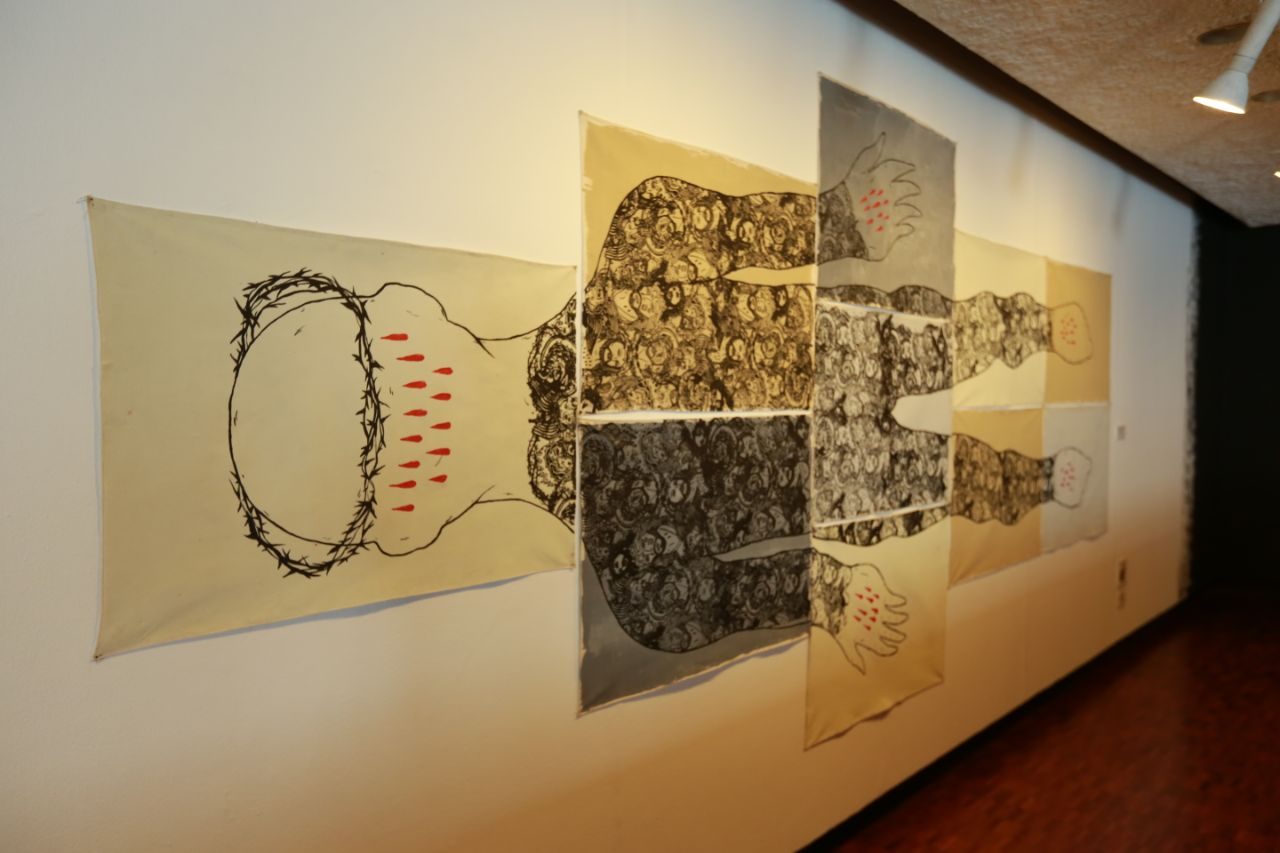

In 2017, Fontanilla held the Kristo y Kristos exhibit at the Cultural Center of the Philippines. The exhibit took inspiration from the devotees of the Black Nazarene, and combined religious iconography with tattoo and street art motifs.

Before the exhibit, Fontanilla also interviewed Quiapo denizens about their devotion to the Nazarene. It was an investigation of street-level religious practice, and people’s faith in a version of Christ that Fontanilla refers to as “Kristo ng Lansangan.”

This so-called Christ of the streets serves as the perfect embodiment of people’s pain and suffering. And while Fontanilla’s art also tackles what he perceives to be the hypocrisy of the faithful (“Religious, pero paglabas ng simbahan hipokrito pa rin. Hindi mo naman pinapractice.”), Kristo y Kristos also serves as a glue for these contradictory elements.

Make your own future

Before the CCP and gallery exhibits, Fontanilla cut his teeth as a member of the street art collective Pilipinas Street Plan. Under the pseudonym Okto, he hit walls and slapped stickers while maintaining a day job.

“I made and designed stickers on my own. I would get the sticker paper from the supply room and print them in the office. Parang part yun nung essence ng guerilla art.”

Through it all, there wasn’t any intention of going beyond what he was currently doing. “We never imagined that we would evolve as artists. During that time, strike anywhere ka lang. Mga bata pa kasi kami.”

While Fontanilla now has gallery representation, Pilipinas Street Plan – and most street art, really – came from the need to create opportunities outside of the traditional gallery system.

“Kwento nila (members of Pilipinas Street Plan), nagsusubmit sila sa mga gallery pero hindi sila napapansin. Eh ‘di gawin na lang natin sa kalsada for the masses.” (They said that they submited their works to galleries, but were ignored. So, why not hold our own exhibit on the streets, for the masses?)

While most street art is made on concrete, the works are, at best, temporary. They only last until the property owner decides to demolish or paint over the piece. For Fontanilla, that’s not a bug, it’s a feature.

“Kung ginawa mo yun for the street, lahat naman yun ephemeral,” he explains. When a street artist creates a piece on a wall, that artist puts their work up for both public scrutiny… and public tampering. It isn’t uncommon for a street artist to later find their work covered with tags and stickers from other artists.

Fontanilla considers that part and parcel of making art in public spaces – and even part of the artwork’s story. “Kahit nga yung commission wall mo, binaboy ng ibang tao, ok lang yun. Nasa kalsada kasi siya. Hindi mo naman kontrolado yun, unless iuwi mo nalang yan,” he says, “Iniiwan ko yung mga tags. Part yun ng istorya ng pader na yun. Collaboration-interaction yun ng kung sino man gumawa nun.”

(Even on your own commissioned wall, people will vandalize it, but that’s how it is, since it’s public. You can’t control it, unless you bring it home. I just left the tags there. It adds to the story of the streets. It becomes a collaboration.)

Evolution

Eventually, Fontanilla decided to pursue a career as a gallery artist. “I had to evolve,” he explains. “Alis na ako sa pagiging Lost Boy sa Neverland; grow up na ako,” he adds, laughing.

This evolution also meant shedding his old persona. “Why would I bring Okto to the gallery?” Fontanilla asks. “I killed Okto; so si Auggie na lang.”

As an exhibiting artist with roots in street art, Fontanilla continues to take inspiration from the urban experience. His paintings and murals draw heavily from everything from Jeepney art, prison tattoos, American hot rod designs, and cheap posters “printed on tarps and displayed along Recto.”

Along with the proliferation of corporate-sponsored street art, Fontanilla sees a new generation of artists who spend more time on social media than bombing streets.

“Porke’t malakas ka lang sa social media, kukunin ka ng mga sponsor dahil ‘sikat to,’ or ‘maraming followers ito eh.’ Kung dun lang yung basehan, eh di wala nang sense yung ginagawa nung mga talagang nags-street art noon.”

(Just because you have a large following on social media, sponsors will reach out to you just because you’re ‘famous’. If that’s the only basis, then what real street artists do makes no sense.)

Fontanilla thinks a street artist’s reputation should still be measured in actual street cred, instead of likes and followers. “I think it would be better if you paid your dues on the streets,” he says, but also maintains that it’s a “case-by-case basis pa rin; no hate.”

Fontanilla, for his part, will continue to embrace the grimy roots that have nourished his art. “Nandun pa rin yung influence ng kalsada; yung madumi,” he says of his works.

“Kung magulo, eh di laruin mo na lang ang environment mo!” (The “dirty” influence of the streets will still be there. If the environment is messy, then just go with it and do what you can!) – Rappler.com

Iñigo de Paula is a writer who lives and works in Quezon City. When he isn’t talking about himself in the third person, he writes about pop culture and its peripheries.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.