SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Journeys of consequence – the ones worth taking – remake the man, just as many stories worth reading end with a protagonist forever changed.

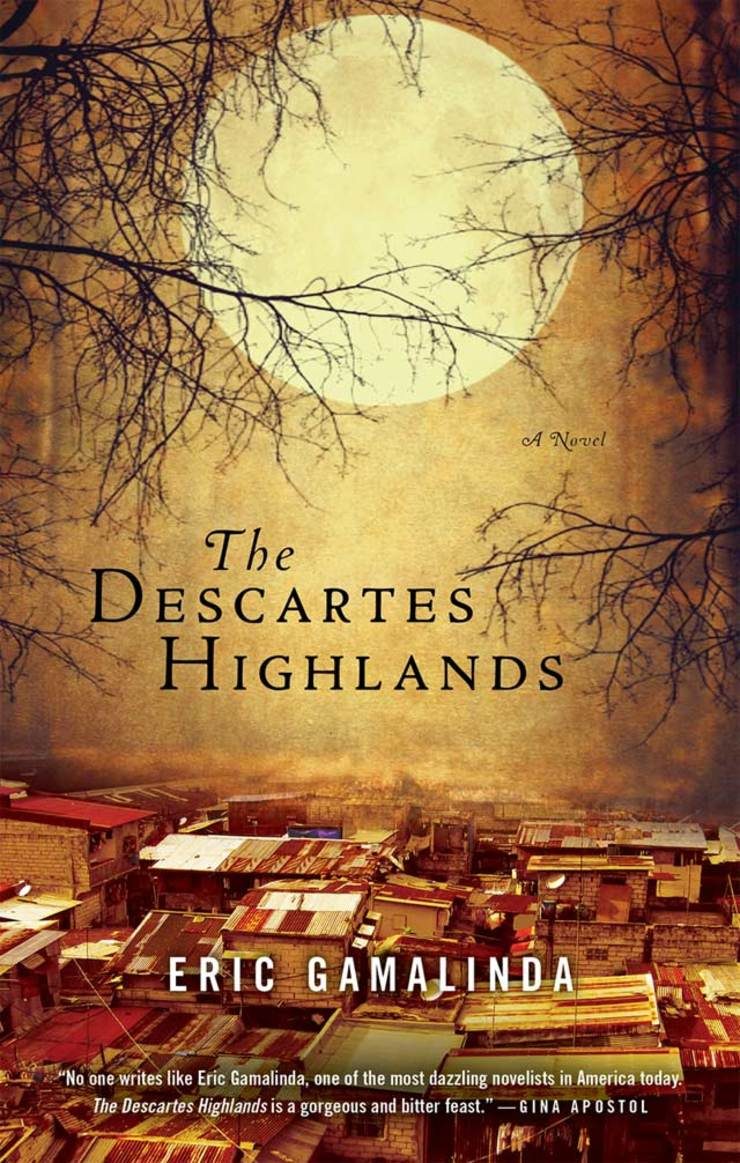

After a decade since his last novel – My Sad Republic, first place winner at the 1998 Philippine Centennial Literary Prize and 2000 Philippine National Book Awardee – acclaimed author Eric Gamalinda returned with The Descartes Highlands. The book was shortlisted for the 2009 Man Asian Prize. It was published this year by Brooklyn-based Akaschic Books.

The Descartes Highlands’ language is distilled and potent, admirably forthright and brutally vivid, much like the New York environs he has inhabited for a decade. Where once his words gilded and festooned the world he offered, now they strip down and cut open to reveal the characters that he sacrifices to his readers.

Gamalinda’s new hard-hitting novel’s narrative begins with a body blow to the reader: A woman whose partner owns an abortion clinic at Dobbs Ferry, New York, longs to have a baby by any means necessary. It quickly plunges headlong into the gritty streets of Manila on the eve of martial rule in the Philippines, and just as quickly shifts to a present day honky tonk bar in Thailand, among others.

Even The Descartes Highlands’ point of view is startlingly refreshing. It is written strictly in the first person, swiftly shifting from one character’s perspective to another, empowering the reader like a demon able to possess and inhabit any person at a moment’s notice.

Stranger before me

Gamalinda confides that, like many overseas Filipino workers, migrants, and expatriate artists, he felt living abroad was necessary and would necessarily change him.

“It was something that I wanted to happen to me. I knew that my perception of my home country would be altered by my immigrating to the US and I was looking forward to that. I think I’ve been able to observe the country a little more objectively because of the distance. But also, at the same time, I think I’ve strengthened my affection for the country, probably because of home sickness. Looking at it from a longer distance, I think I am able to empathize a bit more about what’s going on here and also be proud of what’s going on here,” he explains.

Gamalinda confesses to being acutely aware that he is now published in the United States for a global readership. “Now that I lived there, and now that I’ve also traveled much more abroad, I am aware of an expanded audience. I’ve had people telling me that they’ve read my work and they’re from Europe or other parts of Asia and you realize we are living in a global world now especially with Internet and it does, I think, unavoidably affect the way you write.”

No longer could Gamalinda simply write the way Filipinos talked, thought, or repurposed the English language. He could no longer assume that all his readers knew the Philippine context of what he wrote about. He explains, “When I was writing back here, I knew that I could write whatever I wanted to write as long as it could connect with my Filipino audience. I think Filipinos love to play with language and we understand that, if we read something linguistically experimental, we get it because that’s the way we talk when we use language. Americans don’t understand that.”

He elucidates: “Whenever I write something very specific about the Philippines, I have to figure out how to say something that I know everybody on a universal level would understand and yet not be so offensively explicatory. The international audience might say, ‘Oh we get it.’ But the Filipino reader might say, ‘Why the hell does he need to explain that to me?’ So it’s a balancing act. But I like the tension.”

Gamalinda acknowledges that his work has evolved. “When I was in the States, my relationship with the language changed. I was getting more attracted to simple, direct, and hopefully more elegant language because it’s pared down. I was really starting to dislike the Latin American Baroque stye that I used to do in My Sad Republic. It had a lot of flourishes, a lot of images. I decided that I wanted something completely new, stripped down, and more in-your-face.”

The Descartes Highlands: Organic, unpretentious, unmannered, vigorous, and compelling, this novel grabs you by the collar and never lets you go.

Writing and publishing in the United States may have distilled his language and made his storytelling even more rigorous and conscientious, but it also brought to bear a pressure to conform to what American readers and publishers expected of contemporary Asian-American literature.

Gamalinda reveals that he resisted attempts to make his story formulaic and his characters stereotypical. “I have spoken to a number of publishers who did tell me that they wanted me to write in a specific Asian-American way,” he admits. By “Asian-American way,” the publisher meant stories that explore family ties, generational conflict between parents and children, the experience of being between two cultures yet fitting in neither, and of uncovering secret pasts left behind in the old country. Gamalinda stood his ground.

Gamalinda further reveals that he was even told to censor his own story by one publisher fearing for the sensitivities of pro-life Christians. He confides: “The first publisher that approached me was very interested. It was one of the big 5. But they said, ‘Can you get rid of all the abortion stuff?’ I think they were afraid because it’s a very touchy topic. And I said, ‘I can’t because it’s crucial to the story and you got to see the irony because this guy is adopted but his mom aborts babies. If I take that out then his entire story will fall apart.’ And they said, ‘Just try rewriting and see where it goes.’ I sent them a version with the abortion stuff still in it, and they said, ‘We really love it but we can’t publish it.’”

There is nothing in Gamalinda’s work that espouses for or against abortion. It is simply a circumstance that highlights a character’s predicament.

Gamalinda admits that he found finishing his latest novel difficult. “It took 10 years because of the subject matter, because of the complexity of the story, and also because I was going through so much change at that time, that period when I was reassessing my own work, even my style of writing.” But as with any master in his field, he has made his work seem effortless.

Human of New York

For Filipinos who can only dream of being published in New York, it is easy to assume that an acclaimed writer such as Gamalinda had it easy. Humble and honest as he is, he confesses that the truth was quite the opposite.

He narrates: “I work two days a week. I’m the Development Director [at the Clemente Soto Velez cultural and educational center], which means I raise money for them and I’m a one-person department because I’m the only person that they could afford to have. I teach one day at Columbia but only during the fall semester. I decided to do that part time job last July because I realized for the last 9 years, I had been working in fund-raising full time and it was just sapping all the energy from me. I realized during that time I was not producing anything creative.

“So this guy who runs his organization, I just happen to call him and I told him, ‘I’m gonna start looking for a new job, can you be my reference?’ And he said, ‘I wish I could offer you something, but I only have a part-time job here. Would you be interested in taking it for this low salary?’ So I did the math and realized I could do that. Now I think I have some kind of balance. I don’t get paid much but at least I get to go away.”

He declares: “I don’t think residing abroad will solve the problem. I think it’s hard to be a novelist wherever you are, unless you’re somebody like Stephen King who makes money every time he writes; some people who might get lucky because they hit the right note and whatever they write immediately sells. But if you want to write a book that really matters to you even though you know that it’s not going sell, then I think you have to be ready to make sacrifices and persevere, and it doesn’t matter if you’re living here or if you’re living in the States.”

Out of the picture

In his latest novel, Gamalinda has purposely avoided writing in the third person or using an omniscient narrator. And unlike other novelists, he refrained from turning his novels into fictionalized autobiographies.

Asked if he is to be found in any of his novels, he responds: “Hopefully none, because my characters are so messed up. I really wanted to remove the voice of the author. If I wrote it in the third person then that’s me again intruding into the story. That’s why I used first person narratives. I’m fascinated by that technique of completely removing the author from the book by just having the characters speak. I really enjoy it, and it’s something that I’m actually thinking about for the next book.”

By appreciating the restraint by which he omits his own ego and the vigor by which he creates such vivid images and such vital characters, the reader finally finds the new Eric Gamalinda between the lines. – Rappler.com

For details, visit akashicbooks.com and ericgamalinda.com

Writer, graphic designer, and business owner Rome Jorge is passionate about the arts. Formerly the Editor-in-Chief of asianTraveler Magazine, Lifestyle Editor of The Manila Times, and cover story writer for MEGA and Lifestyle Asia Magazines, RomeJorge has also covered terror attacks, military mutinies, mass demonstrations as well as Reproductive Health, gender equality, climate change, HIV/AIDS and other important issues. He is also the proprietor of Strawberry Jams Music Studio.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.