SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[Ilonggo Notes] Iloilo through the eyes of Felix Laureano, the first Philippine photographer](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/10/Ilonggo-Notes-Oct.jpg)

It was at the 148-year-old Panaderia de Molo, just across the road from our house and one of the country’s oldest bakeries, that I happened to see the English translation of “Recuerdos de Filipinas – Album-Libro util para el estudio y conocimiento de los usos y costumbres de aquellas islas, con trienta y siete fototipias tomadas y copiadas del natural” by Felix Laureano, first published in 1895.

The 2001 English version, translated and edited by Felice Rodriguez, Ramon Sunico, and Renan Prado, is titled “Memories of the Philippines – A tool for the study and understanding of the ways and customs of these islands, with 37 phototypies taken and copied from real life.” Laureano dedicated the book to the painter Juan Luna y Novicio, in acknowledgement of his talent as an artist.

I was blown away and begged to borrow the book for the weekend.

Felix Laureano is considered to be the first Philippine photographer. Francisco Villanueva writes that he was born in 1866 to a landed family in Patnongon, Antique, and grew up with his siblings in neighboring Bugasong town. His parents were Norverta Laureano de los Santos, a widowed businesswoman, and the parish priest, Manuel Asensio, an Augustinian friar from Zamora, Spain.

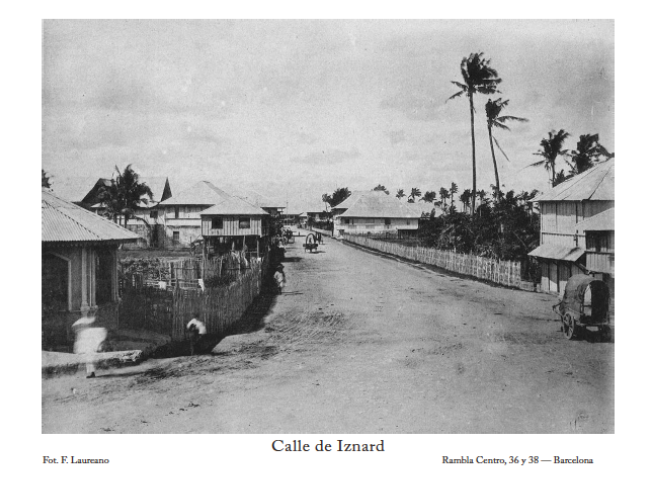

Laureano studied at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila in 1883. He had his first exhibit in 1887 in Madrid when he was 21, where he won an award. He traveled to Europe and studied photography in Paris before returning to Barcelona, where he became a professional photographer and established two studios, including Gran Fotografia Colon at the popular “Las Ramblas” area. He also had studios in Calle Iznart in Iloilo City. Spain’s leading illustrated newspapers published his work.

The family returned to the Philippines during the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s and lived in Iloilo City until the end of the Japanese occupation. They later moved to Manila, where he died on December 18, 1952, at the age of 86.

The English version has 37 photos and 170 pages. It is probably the oldest “coffee table” book in existence about the Philippines; it focuses mainly on Panay (Iloilo, Antique), where over half of the photos with location details are taken. He also describes the Ati-Ati and the Sinulog or Moro-Moro dances. The original Spanish edition has a digitized copy at the Falvey Memorial Library of Villanova University in the US.

It is a delightful read because Laureano does not only let the photos speak for themselves, but he vividly describes the scenes, with some of the essays running to several pages of text, where he very frequently uses Ilonggo terms and translates them for his readers. Most of the terms are still in common use today. In a way, it can be considered not just a photo album, but also a work of linguistics, geography, and anthropology, with his descriptions of people, places, rituals, customs, and day-to-day events – Filipino types, a wedding celebration, a child’s funeral, washing clothes, bathing in a river, husking rice, growing oysters, food stalls (“calenderia”), markets, types of trees and fish, the landscape, carabaos – interspersing them with stories of local myths. It appears to be written for those who might want to visit the exotic and faraway colonies but also as a way of recording the daily lives of people in their own milieu, out of the usual posed portraits in studios popular at that time.

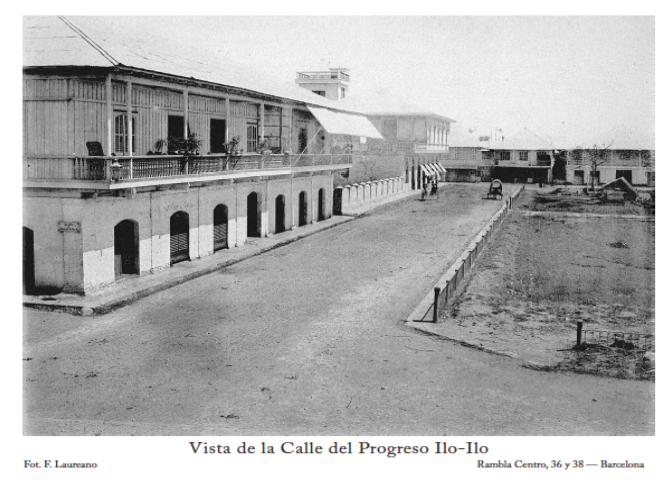

His description of the Calle del Progreso intrigued me, so one day I hopped on my bicycle and tried to trace the street (now known as De La Rama) that he describes as, “…the best street in Iloilo, exceeding Calle Iznard and Ordas Boulevard (now named JM Basa St.), being the street of the upper class, the moneyed aristocracy…buildings that beautify it and give prominence to its name are elegant, semi-palaces of oriental luxury…the grand house of Samuel Bisschoff, a German, who has amassed a great fortune selling watches…the row of houses of the Oppens, the millionaire Isidro de la Rama, D. Felix Arroyo, the lawyer Emilio Valenciano, Cornelio Melliza, Captain Miguel, and commercial offices of Jorbes, Mm Ker & Co., Smith Bell and Co. in magnificent buildings…the street ends in the wharf…”

Alas, none of those landmarks exist any longer, after 125 years, and Laureano would probably turn over in his grave if he saw how Iloilo’s once most beautiful street is now one of the most unsightly – closed off at one end towards the wharf, with shanties and informal settlers clogging the street and sidewalks, electric wires snaking around, and only skeletons left of what must have once been the grand dwellings and offices he gushed over. Some other properties have also been taken over by huge lunok trees.

Only a few reminders exist on the street now named after the commonwealth era shipping magnate Don Esteban de la Rama, and these are buildings of 1930s to 1960s vintage, such as the Taller Bisayas de Strachan and MacMurray, the Art-deco-ish Panay Ice Plant, the sad-looking facade of the Lopez-Kabayao mansion and the former Hotel de Paris beside it, while the once glamorous Admiral Hotel, done in the ’50s streamline modernist style, is now covered up by shanties.

How the fortunes of the street turned sour is a long story, interwoven with the port’s labor strikes, the devastation caused by bombing during WW2, takeover by mafia characters, and gang violence of the ’60s to the ’70s. It is still not a place I would like to be in after sundown.

In another piece he features Calle Iznard (Iznart), “…with its magnificent houses of wooden board and galvanized iron, the grand house of the French Vice Consul, Vicente Gay, its many establishments, Chinese-owned stores on the ground floor, and the French commercial house of Levi Hermanos…” Calle Iznart still runs from the Casa Govierno (Provincial Capitol) and the Arroyo fountain, down to the Plazoleta Gay, Iloilo’s central square, at the junction of JM Basa, Iznart, Arroyo, and Ledesma streets. From there, Iznart’s main landmark now is a recently constructed Filipino-Chinese Friendship arch; it then runs parallel to JM Basa street and ends up a kilometer away at the Maria Clara monument and the Central Market.

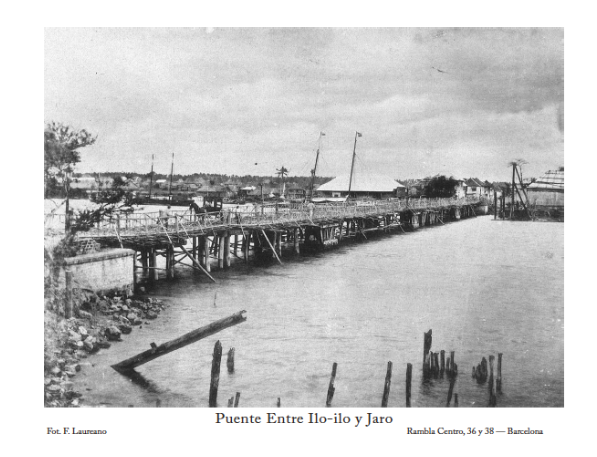

He describes the city of Jaro as being separated from Iloilo by an area called Tabucan, between the rivers Dungon and Salug, where people from the interior towns came on rafts down to Jaro to trade. It is “…an eminently industrial city, with sinamai, jusi, handicrafts, silk handkerchiefs, and embroideries that are universally famous…” He also mentions the notables of Jaro: Eugenio Lopez, Simeon Ledesma, Benito Jalbuena, and Numeriano Villalobos; the prolific poet Sanitbanez; the natural charm and clear intelligence of Jaro ladies Mariquita Lopez and Albina Hopilena. The owners of the principal residences of Jaro are named: Jaro Mayor Teodoro Benedicto; the Jalbenas, Jalandonis, Arguelles, Montinolas, Ledesmas, Arnaez, and the house of the vice consul of Portugal, Claudio Lopez. In separate essays he describes the Jaro Cathedral and bell tower, the bustling and huge Jaro market day of Thursday, or the Huebesan, which continues to the present.

And with Iloilo in its heyday as a center of commerce because of the harbor and the port opened to world trade in 1855, he also has two photo-essays that describe the Iloilo wharf and the types of schooners, boats, and their cargo docked there. He describes the Plaza of Iloilo (later named Plaza Alfonso XII and after the Spaniards left, as Plaza Libertad) as “…a perfect square, adorned by pretty gardens, its edges bordered by Talisay trees and other shade trees, with iron benches…all the elegant and beautiful people of Iloilo promenade here on Sundays and holidays…” One essay features the Plaza de Toros de Iloilo, the only bullfight arena outside of Manila, though he is not at all impressed with the ability of the amateur bullfighters: “…they do what they can with what they know, but nothing more, they have never fought bulls in their lives….” He is not impressed with the bulls, either, describing the poor hapless animals as “better fit for eating than fighting…useless, with neither strength nor weight…small, timid, they neither kill horses or make the picadors fall off their horses…”

Much of it is entertaining, written in a style which we might now term as archaic, and reflecting (probably) typical upper class, male, ilustrado views, condescending at times, and disparaging towards some ethnicities like the Aetas, Moros, and Chinese traders. Some parts, on the majestic (and now long gone) Oton Basilica and its interiors, are written by a contributor whose writing style is effusive, quaint, and given to hyperbole. That is, of course, a judgment of our own times, for who knows what other readers will think a century from now? Perhaps they will relate to it in the same way, as I have, with the Rodriguez introduction: “It is as if windows had swung open, revealing scenes of a century ago…” – Rappler.com

Vic Salas is a physician and public health specialist by training, and now retired from international consulting work. He is back in Iloilo City, where he spent his first quarter century.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Ilonggo Notes] ‘Lunok’ and ‘mari-it’ in Iloilo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/08/tl-collage-sq.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[WATCH] PhotoRap: The future of photography](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/06/photorap-future-photography-sq.png?fit=449%2C449)

![[Ilonggo Notes] Putting the spotlight on Ilonggo and regional cinema](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Screenshot-2024-04-07-at-2.04.59-PM.png?resize=257%2C257&crop=321px%2C0px%2C809px%2C809px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.