SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

One day in November 2020 visual artist Charlie Co got a call. It was an acquaintance asking, “May obra ka da (Do you have any work available)?”

That’s a question Co, a painter, sculptor, and terracotta artist, has heard often since Negros Occidental’s young turks crashed the salons of the pampered class in the 1980s with their socio-realist themes of injustice and war.

But that call stood out among the thousands he’d taken over a four-decade career.

When he got it, Co was in the hospital, battling COVID-19.

“Nagasala doctor ko (My doctor was in a panic).”

The odds of Co surviving the virus were poor. Diabetes had ravaged his health since youth, leading to years of dialysis and, eventually, a kidney transplant that left him with a weak immune system.

Artist friends and staff at the Orange Project, a gallery he co-owns in this city, also faced a deluge of inquiries.

Art investors readied to pounce on an opportunity.

The pandemic had created a buyer’s market. The artist, while at the “elite” level, was looking at horrendous medical bills. And, given Co’s medical history, he could very well end up a statistic, death number X.

“Daw ako nahuya (I was the one who felt ashamed),” architect Hilario Campos Jr., one of the gallery’s junior artists in residence, said of those days.

Eight months into surviving that brush with death, Co chuckled at the memory.

“That’s how cruel the world is,” he quipped as both hands slapped at a long table on the gallery’s second floor.

Staff groaned as he reached for a round cookie covered with a crust of white sugar. Co smiled, shrugged. “That’s just a side story,” he said of that vignette on life’s cruel ironies.

“Hambal ko, may ara, bayad to sa ospital, a (I said, yes, give the payment to the hospital).”

Shared mortality

Co can shrug off that little slice of sordid because his mind’s focused on 20, 30 years from now.

“Artists have the responsibility to show the importance of the time we live in. What will they say of today?” he pondered. “Will a young artist in the future say, see how they cowered? Or will he say, look at how they endured and fought back?”

Besides, harsh realities have always been his work motif.

The artist grew up under Martial Law in a province where the land birthed riches or starvation, depending on which side of the socio-economic divide you stood on.

He and other Negrense artists formed the Black Artists of Asia in 1986, forcing the art world to confront life in the shadow of the social volcano. Many gravitated to social realism.

Co, who was named one of the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ 13 Artists in 1990, has always been more of a surrealist, capturing grand conflict with a lens that is intensely personal. His style adjusts to whatever vision bathes canvas or paper but, always, with iconography that leads back to him.

Co does not forget, will not forget. Yet neither is the self-confessed news junkie trapped in a sliver of time – or space. In 2020 he expanded his 2017 exhibit “Guerra Guerra” (Ilonggo children’s singsong call for war games), weaving universal themes of conflict, be this in Aleppo or Marawi, or the war that shaped his mother’s generation, while interrogating both subjects and audience’s motives and goals.

A small room off his home studio houses old brushes and palettes, and parchments holding the origins of a finished work. They are reminders “that I have to do more, to never stop learning.”

A stack of paintings leans on the wall of an alcove to the side of the studio loft. He pulls them out, piece by piece.

There’s a self-portrait of a man on his side, a tube jutting out of his torso. A blackbird stares down, waiting.

There are women waiting their turn to entertain men in a bar, from the era of sex tourism during the Marcos dictatorship.

A man trains his slingshot on tuxedoed creatures with pig and crocodile snouts.

“Happy” slaves perform for their master. A life-sized clown/robot looms over them, plastic skin showing a constellation of scrip, actually blister-packs of medicines Co has had to take through the years.

One painting reflects still unfinished business from the ’70s and ’80s. Two men, one with a fossilized visage, face each other in cushy chairs, the kind we see in exclusive studio interviews. A river of skulls flows beneath a flag. A crucified figure dissects white, red, and blue.

And then there is the horseman of death galloping across a bristling, red metropolis.

Co’s art blends humor with anger and defiance.

Pandemic

2020 was a big year for Negros artists. The Visayan Visual Arts Exhibition and Conference (VIVA EXCON) art festival was coming to the land of its birth on its 30th anniversary. The hosts had spent four years preparing.

The biennial theme is Dayun Kalibutan.

Kalibutan is the Ilonggo word for the world. It can also mean personal consciousness. Dayun can translate to “come in,” an invitation. Or, more in keeping with the fluidity of the art world, it asks, “what’s next?”

Co knew digital technology would ease the forced shift in viewing platforms.

But there was now a deadly race. The national capital was going on lockdown. And so was Bacolod.

Most artists were looking at the very real prospect of hunger.

They weren’t on any clear category for aid: not regular workers, not even contractual workers; neither were they on the poorest of the poor list. Most fell between the cracks.

Co met with Viva Excon movers Manny Montelibano and Toto Tarossa and discussed how to help local artists.

The gallery had some money from previous exhibitions. He approached Victor Benjamin “Bong” Lopue, scion of the Chinese-Filipino clan that owns Bacolod’s oldest grocery chain, landlord of the 8,000-square-meter Bacolod Art District that hosts the Orange Project, the Art Association of Bacolod, and other smaller art establishments. He is also part-owner of the gallery.

They immediately bought food for 40 artist families under the #ArtHeals concept. Each family received P5,000 worth of food and health products, enough to last a month.

Then artists started reporting underserved communities. Raising funds with an online exhibit, #ArtHeals bought food for 150 families. They trekked up and down mountain trails, and hauled boxes across rivers, to reach villages in Patag, Silay City, and other areas.

In March 2020, people thought in terms of a month or two.

As sickness and death spread, Co realized they were in for a long haul.

The project expanded. Before 2020 ended, they managed seven waves of exhibits that provided income for local artists and sustained their outreach. All artist groups pitched in, a smorgasbord of talent and styles.

Co led the first exhibit, raising almost P1 million. Half of that they coursed through the Negrense Volunteers for Change.

“In an emergency, you find the most efficient way of sending aid,” he said. “They have grassroots reach and they have scale.”

NVC bought personal protective equipment sets for doctors and food for 300 families.

#ArtHeals also helped a group of young residents at the regional hospital who spent their days off the ward cooking and distributing food and food packs to daily wage earners and the homeless. They made makeshift face shields and masks for medical frontliners. They even raised funds for animal welfare groups.

Aid for the artist community reached filmmakers, musicians, even the crew of pizza parlors around the art district.

Co was too vulnerable to go out on food runs. He learned to step back and let younger artists manage the program.

Feeding the soul

Multisectoral aid campaigns and the local government’s ayuda system stabilized after a few months. The artists also realized they were pushing their luck, possibly risking their families.

With the adrenaline wearing off, they found themselves staring at another threat – to mind and soul.

In January 2020, following the news from Wuhan, ground zero of the pandemic, Co had wondered aloud. “How can you place 5 to 10 million lives on lockdown? What happens to people?”

As 2020 drew to a close, he knew artists would have to start healing.

“I can sell online. But I will always need personal engagement to be creative,” said Co.

Young artists still in the exploration stage were hit harder.

Campos, in his 30s, falls in the middle-age group. The Orange Project junior artist in residence has a distinct, playful style that mocks traditions and conventional wisdom – he’s placed Hitler, as part pin-up wannabe, part navigator, atop a local bus.

“I like hanging out in coffee shops and bars, getting inspiration from chatting with friends or snippets of overheard conversations. I struggled hard at the change or routine. It was a different kind of loneliness and sadness,” he told Rappler.

Campos’ day job in architecture allowed him to leave his home.

“But when you see how empty the streets are, it shakes you. Cities are built for people and suddenly they’re gone. The world became a blank canvas, life obliterated by an unknown enemy. It was very sci-fi, but it was my life.”

The slowing down of time was deadly for mental health, recalled Campos. “You may think, but now you can paint and paint, but then you’re cut off from your lifeblood.”

“It was too dark, emotionally, mentally, physically,” said Co.

The artist knows all about isolation. He had served time in “a plastic prison” during illness.

As a young artist in a business-minded family, he struggled to find understanding. His parents and siblings loved him but were bewildered.

“Artist? Wala kuwarta da (There’s no money there),” was the common response he got.

Co may have learned to laugh off things he can’t control. His art shows the hurt inside.

Back in 2017, Co painted “Gone Mad,” three men trapped by confusion and guilt.

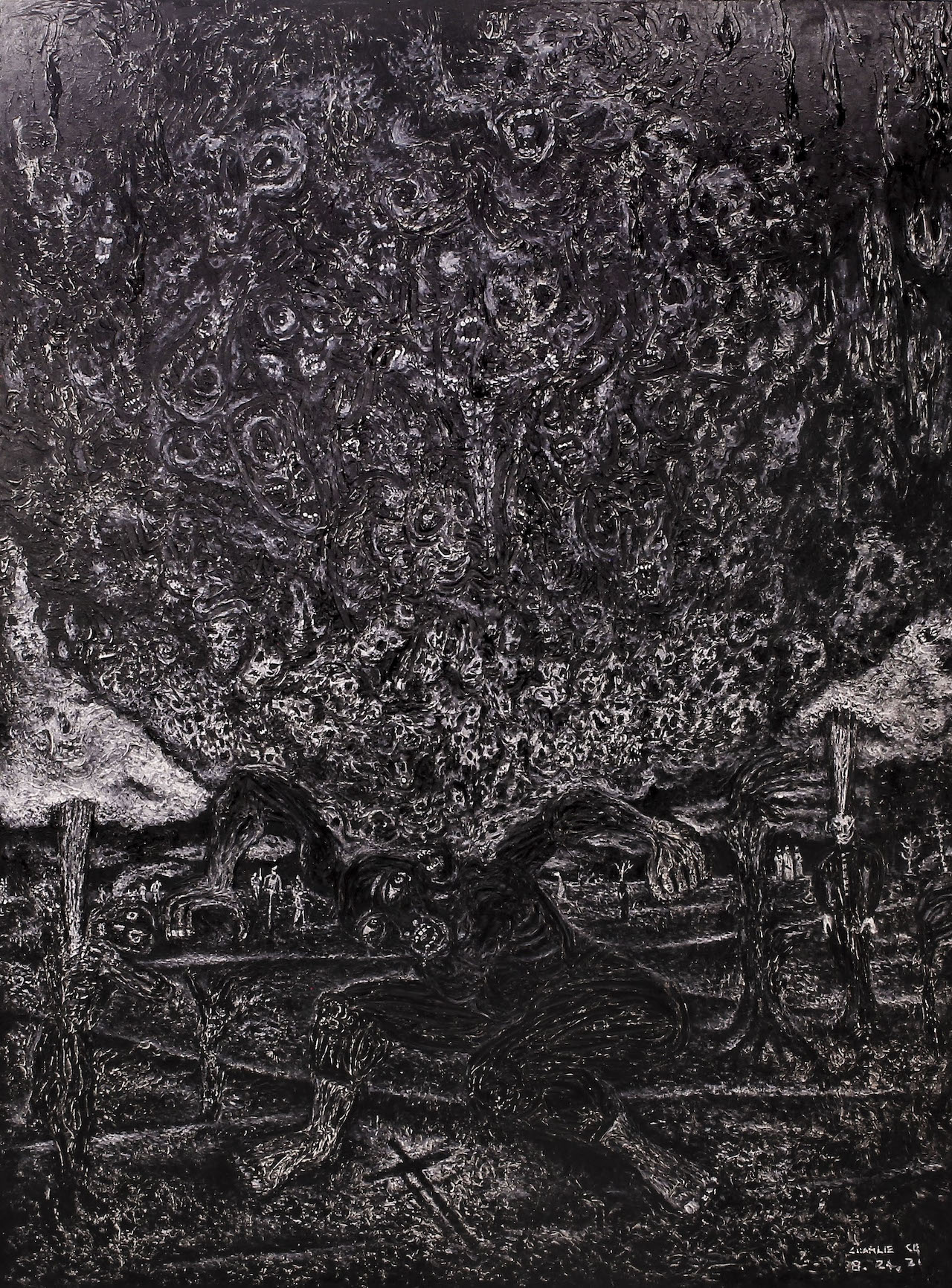

His new diptych, “World Gone Mad” is a massive piece about souls in torment. There is nothing playful about it. You do not know whether the packed characters are showing the anguish of victims or howling as they psyche up to attack.

There is a video of Co working on his obra. It is in itself surreal, the dulcet piano tones of Chopin’s Nocturne in E Flat mixing with the brusque scrape of his brushstrokes, punctuated now and then with thuds.

On the side is a monstrous figure, a horse raging in the throes of torture.

Co can at times seem languid, like a college don. At work, he is very physical, robust.

Shoulders rolled and arms stiffened as he described slapping modelling paste on canvas board, creating staccato sounds of war while at work on “Reflecting De Bruyckere,” a tribute to Belgian artist Berlinde De Bruyckere‘s monumental sculpture on the phantagorisms of anxiety, art that rouses fight or flight reactions.

It was time, Co decided, to start feeding like-minded souls.

“Artists, we’re sponges, we absorb everything. Every day, we listen: ‘Patay siya, patay siya, patay siya’. We dodge the bullet. We absorb. The greatest frustration is, indi ko mapa guwa.” (I can’t let it out.)

“No work, no money,” Campos pointed out. With barely enough to feed their families, artists could not buy work supplies, could not reach their market.

The artist community itself had to take a leap of faith.

“We had to sustain the bonds made, the knowledge-sharing network slowly built up through the years,” Co said.

The art district, in human terms, is adolescent. Established in 2010, it is Bacolod’s center for artistic collaboration. Co founded the Orange Gallery, the precursor of the Orange Project, in 2005 to plant that seed.

“We are always engaging and trying to find out what events we can hold in the space, and who benefits from the space,” he said.

That proved the key to survival in a pandemic.

Established and young artists collaborated to raise funds for workshops, to gain time for the languishing cafes. They created outdoor installations and filled the walls with murals.

Never mind that the streets were still empty.

Digital media helped spread the news. As quarantine levels ebbed and rose, people trickled in.

Young blood

The first collaborative on-site was “Art and Isolation.”

Co rubbed his arms at the memory.

People in masks and shields came in small batches.

“What I remember is the silence,” he said.

It was like coming out of a nuke shelter and seeing the world had survived Armageddon, but also knowing bombs and people who push the buttons remained out there.

But more than that, Co said, “it was people learning from all these different artists, that they are not alone.”

“Charlie knew young people had it the worst,” Campos noted. “So that was our focus.”

Teens technically aren’t supposed to leave their homes. But no young person can stand a year-and-a-half indoors.

They were the first to come, these refugees from online schools. Some didn’t do art but basked in its embrace. Astronauts. Horses. A carabao in a death-defying tilt. A young couple, all in white, face the sun, a hand clasps a red bouquet.

Dancers who could no longer practice in government parks came to the art district grounds. Youth sprawled on grass and cement walks, drawing feverishly. “They walked up to anyone older, who looked like an artist, and asked and asked and asked,” said Campos.

A gift from Mercedes Zobel allowed for the expansion of programs.

They opened up collaborative spaces again and held small workshops.

The young dancers now have a studio.

With every small space that opened, people responded with more help.

“If they see where the aid goes, people will help,” said Co.

The pandemic didn’t affect the market of established artists, as he learned in the hospital. Rich people will swap vacations with acquisitions.

That helped raise more than a million pesos because artists like Elmer Borlongan – “just one word and you have 200 offers,” said Co – and Mark Justiniani donated works to raise money for the community.

They left Co time and means to focus on those seeking to carve their own niches.

“Local becomes very important, even in a world where the virtual allows us to reach across national borders,” he said.

Co walked around and told the junior artists to spot the hungriest souls. He handed out sketchbooks to artists of all ages.

“Just draw. Come back and show me.”

Art as medicine isn’t a unique concept. But seeing results up close and personal, “that’s something money can’t buy,” said Campos.

They opened gallery shows, joint exhibits. Junior high school students became part of that. Older, struggling artists found a local market in the art fair tents that sell works from P1,000 to P20,000.

Expression bloomed.

“The pandemic made me more conscious of creating more important pieces. We know nobody is safe, not yet,” Co admitted.

‘Lukdo’

Artists, freed from isolation, can express doubts and fears without imploding.

Facts can make us despondent. It’s vision that prompts us to seek a way out.

Co pulls out his phone.

“That’s my ‘Guernica,’” he said, referring to Pablo Picasso’s masterpiece on the Spanish Civil War.

This new, very new work is unlike Co’s other paintings.

The 7-by-10-foot work is all in black and white, dense with a multitude of details.

Even on the small screen, your eyes travel and probe into images and details. On a three-inch wide monitor, you see a story here, another story there.

In the studio, “Lukdo” (Ilonggo for burden) has a hypnotizing force

Co’s play of light and darkness leads you into many tunnels. There is a fissure of fear until you realize that in almost every “story” here, there is an out, a safe space waiting.

It’s all about war. It’s also all about hope.

There is the cross, a recurring motif in Co’s paintings.

“Last night, I saw Jesus there,” he said.

You try to find words in response to that.

Co doesn’t overthink when he works. He’s instinctive, intuitive, almost spontaneous, even when making murals.

He did the cross at the bottom consciously. But just the night before the interview, he spotted a smaller cross on the upper portion of the painting.

He shrugged. “Maybe it means I’m protecting my faith, not just my faith protecting me.”

Light isn’t just from some external, cosmic force.

Co segued into Afghanistan, the tens of thousands of dead, barely two decades after tens of thousands died in a war against communists, and then another war against a country that attacked to save the world.

“What do the young think? What will they think in the future?” he mused.

Co hunched over in front of the painting to express internal burdens.

“I am always being reminded that life is transient, that every moment is important, that every encounter with friends and loved ones could be your last.”

Whether in Afghanistan, or Marawi, or the teeming urban jungles held hostage by a virus, the questions will be universal.

“If our spark dies, they will say, ‘they surrendered,’” he explained. “I want them to remember that our generation fought really well.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.