SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

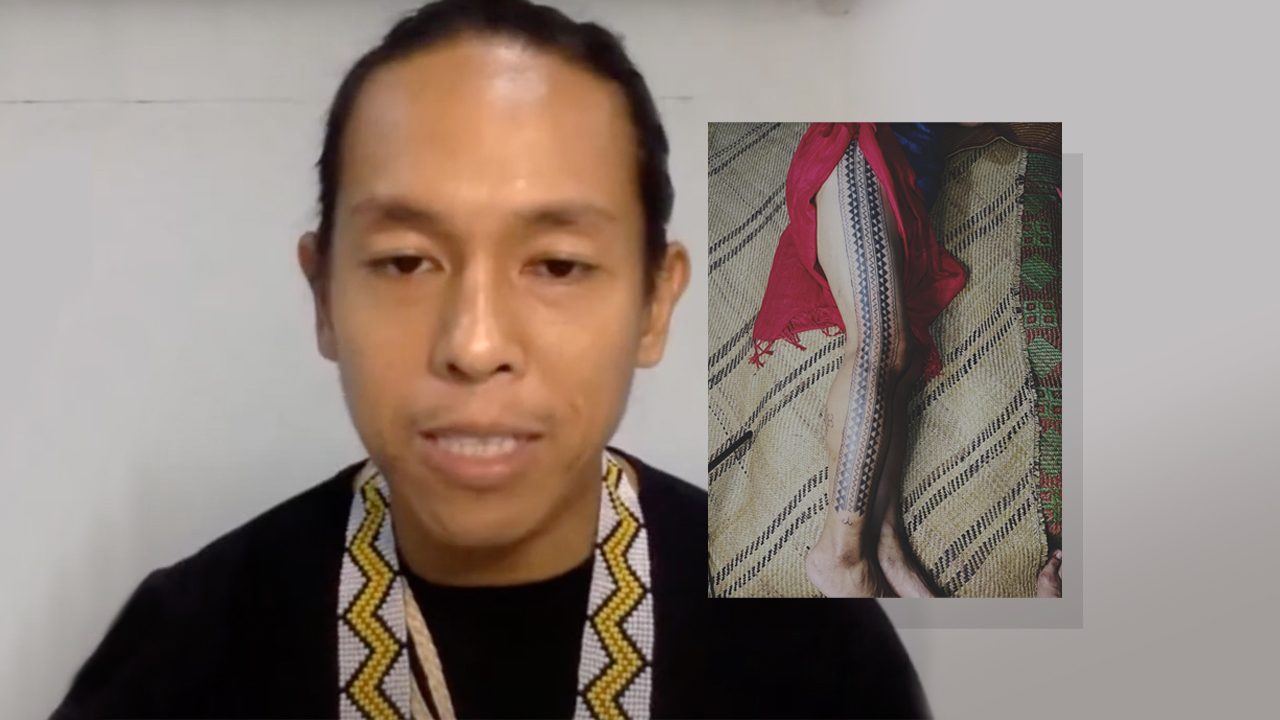

CEBU CITY, Philippines – Piper Abas has been practicing traditional Mindanao and Visayan tattooing for five years. But before this, he spent 13 years researching Philippine traditional tattoos.

He said that what sets traditional tattoo practice apart from the modern practice of tattooing is its ties to the community. Unlike modern tattoos, traditional tattoos are markers of your role in society. Its significance lies not in the meaning assigned to it by the tattoo bearer, or by the aesthetic quality of the design, but by the meaning it holds for the community.

And for Abas, a member of the Higaonon tribe in Mindanao, his work on traditional tattoos also led to him a personal quest towards the uncovering of the essence of these thousand-year-old markings: identity.

Lineage

Abas recalls growing up in Bukidnon under what he describes as a “mixed” upbringing, influenced by the metropolis and the remnants of traditional indigenous culture. As a consequence, the traditional tattoo artist admitted that he did not know how to speak the native language in Bukidnon growing up.

“Para sa akoa, it was not really taken seriously kay ang society dinhi sa Mindanao, majority mag Bisayana man gud,” he said. (For me, it was not really taken seriously because, in Mindanao, the majority already speak the Bisaya language.)

Among his family, Abas said his grandfather was the only member who held on to indigenous practices.

“Naa na siya’y ginaiingon permamente sa akoa, “aha man diay ka na tawo”. Dinhi ko na tawo sa Binukid. “Dire ka na tawo sa Bukidnon pero di kahibaw sa sinultian sa Bukidnon,” he said.

(He would repeatedly ask me, “where were you born”. [I would reply that] I was born here [in Bukidnon]. He would reply, “you were born in Bukidnon but you cannot speak the language.”)

Eventually, Abas said he also became interested in tattoos as it has become a trend as he was growing up. This, coupled with his growing curiosity about his lineage and indigenous roots, ultimately catapulted more than a decade of academic research for Abas.

“Unsa man gyud ang mga tattoo? Tribal man kaha ang mga tattoo. What does it mean to be in the tribe,” he said. (What is the purpose of these tattoos? They say that tattoos are tribal. What does it mean to be in the tribe?)

And what he later discovered is the inextricable link between traditional tattoos and one’s role in pre-colonial society.

Abas learned that while modern “secular” tattoos are purely under the discretion of the person getting the tattoo including the design, the placement, the artist, and even the meaning, traditional tattoo always puts individuals in the context of the society they belong in.

“Gibutang na siya sa imoha (it was given to you). And the warrior, or the hunter, or the shaman did not choose that design. It was given to them. Mura siya’g gi earn (it was sort of earned),” he said.

“Kung tan-awon nimo sila tanan collectively… naa sila’y brand og unsa ilang role in society. You have a society, you have a community. It’s more community-based, it’s not individualistic,” he added.

(If you look at the tattoos collectively… they carry a brand according to their role in society. You have a society, you have a community. It’s more community-based, it’s not individualistic.)

Recreating the practice

A decade into his research, Abas began taking interest in recreating the tools used by indigenous tattoo artists. This he was able to recreate traditional tattooing tools with the help of researcher Lane Rivera Wilcken, three tribal elders from the T’boli people and two Manobo elder women.

“Eventually, nahimo na nako ang bone tools. Sa akong kaugalingon ko una nagtattoo. Naa dayon ko’y amigo na nagduol sa akoa, duol dayon siya nga gusto siya magpapatik. Hangtod naa’t niduol, naan a sa’y ni duol, hinay-hinay ra gyud sila niduol,” he told Rappler.

(Eventually, I was able to create the bone tools. I first put tattoos on myself. Eventually, a friend of mine approached me to be tattooed. And then more and more people slowly came to me to be tattooed.)

“Most of the designs are extrapolated. Mao gyud na akong gipahibalo na ang kani na designs are extrapolated, based sa research, unsa nakasulat sa archives, cross-referenced to archeological findings,” he said.

(Most of the designs are extrapolated. This is what I always tell people, that these designs are extrapolated based on research, what’s written in the archives, cross-referenced to archaeological findings.)

However, Abas is careful to preserve the cultural value of traditional tattoos.

He says he avoids tattooing based on demand, sticking to traditional body placements and designs in hope of protecting not only the practice of tattooing but most importantly, its purpose in Visayan and Mindanao society. “There is a sacredness sa Patik (in tattooing),” he said.

“Often times, I am prepared with academic [sources], kung mangutana sila. I am ready with that. Pero, often times, ang moduol sa akoa crossed those boundaries,” he added.

(Often, I am prepared with academic [sources], if they ask. I am ready with that. But often, those who approach me have already done their research.)

Revival

It is evident that seeking meaning behind an almost-extinct practice not only carries academic fulfillment for the tattoo artist but has also become a personal journey in understanding his roots. It is in this objective study of history and the larger society before colonial influence that Abas was also allowed a look into the richness of his origins.

But for Abas, the revival of Visayan and Mindanao tattoo culture is not instigated by artists and researchers like him. Instead, it is the individuals willing to be tattooed on who are driving the revival.

“Initially, the revival happens to the descendants who are claiming this. Katong gapa patik. sila ang ga revive (those who get the tattoos are the people reviving this tradition).”

The tattoo artist is a conduit that links descendants to their forefathers, even for a fraction of a moment, during the process of tattooing. It’s then his role to make those who wish to get tattooed understand the historical weight, and to practice the traditional method as closely as he could to precolonial times, to uphold the sensory experience.

“Mura bitaw’g you don’t know what they look like, you don’t know who they are, sa ilang struggle sa colonialism… here you are, nawala imong identity,” he said.

(It’s like you don’t know what they look like, you don’t know who they are, their struggle under colonialism… here you are, you’ve lost your identity.)

In effect, significance not only lies in the having thousand-year-old designs imprinted on one’s skin but also the process of its achievement, giving the individual closure with their forefathers through a shared experience.

“And in that moment na magpapatik ka, kanang bukog sa needle, madunggan nimo ang ‘tak tak tak tak tak’, ma feel nimo ang sakit. Makita nimo ang dugo, mohigda ka sa banig– that moment you felt what they felt. You heard what they heard. And when it’s done, what was part of their skin in ancient times is put on you now. Despite sa loss sa colonialism, in that point in time, nag connect mo.”

(And in that moment that you are being tattooed on, in the feel of the bone needle, in hearing the ‘tak tak tak tak’, you feel the pain. You see the blood, you lay down on the woven mat – that moment you felt what they felt. You heard what they heard. And when it’s done, what was part of their skin in ancient times is put on you now. Despite what has been lost in colonialism, at that point in time, you connected.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.