SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Author Randy Ribay set out to write a young adult novel on the Philippine drug war because it was all he could read on the news.

“In 2016, it was in the headlines here in the United States, it was in the forefront of my mind,” Ribay told Rappler during a Skype interview. It was nighttime in his West Coast home, and he had just met with friends from Malaya, a coalition of mostly Filipino-Americans who are opposed to Duterte’s policies and organize to pressure US lawmakers to act on them.

“A lot of my other friends and I were just feeling at the time that we needed to do something. We wanted to create art that would bring attention to some of these things, to keep the conversations going, in the hopes of doing something with our writing,” he said.

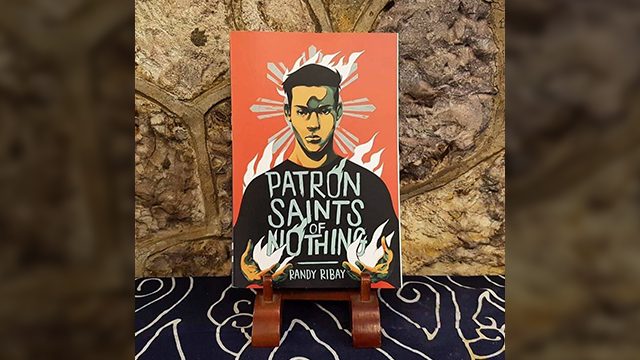

The result is The Patron Saints of Nothing, Ribay’s third young adult novel, a lyrical and fast-paced story that is at once a reminder and a call to action for what has been going on in the Philippines since Duterte came to power – a brutal war on drugs that has killed thousands and left thousands more orphaned and in mourning. (READ: The Impunity Series)

Ribay’s story, since its release in June, has resonated.

It was named a finalist for the 2019 National Book Awards in the US, joining the likes of Akwaeke Emezi, Jason Reynolds, Laura Ruby, and Martin W. Sandler, who are also finalists for the prestigious award under the Young People’s Literature category.

In November, the book was also nominated for a 2020 CILIP Carnegie Medal, which is given to book “written in English for children and young people that create an outstanding reading experience through writing.” The award is considered “the UK’s oldest and most prestigious book award for children’s writing.”

Ribay dedicates his book to “the hyphenated” – people like him born half white and half “other,” people who grew up in the US or elsewhere craving a definite answer to the question, “Who am I?” Ribay himself said he had the Filipino-American young adult demographic in mind when he wrote the book.

The Patron Saints of Nothing started with these questions: “How American am I? How Filipino am I? What right do I have to voice out my opinions about what is happening in the Philippines right now?” In his book, Ribay finds that voice and lets it speak through 17-year-old Jay Reguero, who, like himself, was born in the Philippines but grew up in the midwest, in Michigan.

Jay’s ‘hyphenated’ condition is something many Filipinos in America face. The last US census in 2010 estimated around 3.4 million Fil-Ams living as citizens in the country. And yet even if this minority group comprises around 1.1.% of the US population, making Fil-Ams the third largest immigrant group in America, representation in literature is scant.

“We’re the third largest immigrant group in the United States. I guarantee you there are writers out there, the difficult thing is getting them out on the shelves because there are so many layers of people who have to connect with your story and believe in it,” Ribay said.

These layers of people are often white, he said. “A lot of the people who are reading these kinds of stories in their early forms were the gatekeepers, are people that don’t have a connection to the community, who don’t have the historical or cultural context to connect with that kind of story, so that’s difficult,” he added.

Ribay’s manuscript was picked up by Kokila, a new imprint from Penguin, led by a team of women of color. Kokila aims to publish “stories from the margins…to examine and celebrate stories that reflect the richness of our world.”

“They’re entirely focused on getting these stories out in the world to better reflect the actual reality of what our world looks like,” Ribay said.

Depicting brutality

Even as the book is for young people, in The Patron Saints of Notthing, Ribay pulls no punches.

Its premise is heartbreaking: Jay decides to fly from his cold Michigan home all the way to the Philippines after the death of his cousin Jun in the hands of Philippine police. He is confronted with his Filipino relatives who have chosen to forget about his cousin and be silent about the circumstances of his death. What’s even worse is that Jun’s father is a police officer who is supportive of the war on drugs.

Its project is to talk about the drug war through the eyes of a Fil-Am teen, and it does what it sets out to do. Ribay said he read every article he could pull up regarding the drug war from international and Philippine sources alike. His book pays tribute to this existing reportage. At the end of the book, Ribay even lists recommended reading about the drug war, from Rappler’s Impunity Series, to The Drug Archive, to the New York Times’ “The are slaughtering us like animals.”

Throughout the book, Jay walks the reader through stories of kids killed in the drug war. He mentions Kian delos Santos, a 17-year-old who was killed on the eve of a high school exam. In the book, Jay watches the CCTV footage of police murdering Kian. (READ: TIMELINE: Seeking justice for Kian delos Santos)

“The video shows a group of police officers dragging him into the middle of a vacant lot, hands tiend behind his back and a sack over his head. Then, they removed the sack, untied him, and slapped a gun in his hands. They stepped back and raise their own, pointing the barrels directly at his face.”

“I wanted it to be shocking and not kind of cross that line of exploiting it or capitalizing on the brutality,” Ribay said. “I think people want to protect kids, that we shouldn’t show them these things. I think my job as a novelist is to prepare them for the world, not protect them from it.”

Ribay is also a high school English teacher, dealing with kids who are between 14 and 18 years old. “The great thing about a story is it gives them a safe place to think about [brutality], a safe place to process their emotions via the character that they’re reading about,” he said. He added that giving them this space could prepare them for the world and how they’re going to act on injustices rife in human life. “This is the world, what are you gonna do about it?” he wants his stories to ask.

‘All of it is a part of me’

Jay comes to the Philippines in medias res. “So the drug war continues. The body count rises,” Ribay writes in the first couple of pages. His cousin has been killed, linked to drugs. His relatives’ way of dealing with the death is pretending his cousin never existed.

Young and callow, with very little knowledge of Filipino, Jay flies to the Philippines thinking he would solve his cousin’s death without even devising a plan. In Manila he meets 19-year-old Mia, a journalism student, who Ribay envisioned as the character that would guide Jay through all of his cluelessness.

Mia, smart and driven, helps Jay sort out his clues, guides him through the slums where his cousin once lived.

In true young adult novel fashion, Jay even develops a little crush on Mia – a little connection he holds onto as the rest of his family breaks away at each mention of his cousin’s death.

“I needed some way for him to find connections and to uncover some of these truths, these places, that he wouldn’t have access to if he were on his own, or just with his family,” Ribay said of Mia’s character. “As I revised more and more, her role expanded more and more, and I just came to appreciate journalists more and the work that they do, when they do this kind of reporting.”

So through Mia, Jay comes to know more about the drug war and how complex it is. In one chapter, he meets Reyna and her child, with whom Jun lived for almost 2 years – among the last of his life. In that particular chapter with Reyna, set in the slums of Manila, Ribay implicitly invokes the reality of internal migration in the Philippines, as Reyna comes from Cebu.

In this chapter, the language barrier Jay experiences becomes even more palpable. With the little Filipino he knows, compounded by Bisaya, another language he does not know how to speak, he comes to rely on Mia to give himself the peace of mind he crossed an ocean to get.

And perhaps this is another central theme of The Patron Saints of Nothing: how we come to rely on others to confront things that are bigger than us. “These big systemic things play out at the human level, so I wanted to tell a human story centered on the people are entangled and caught up in it and tell the story through that lens,” Ribay said.

It is through Jay’s relationship not just with Mia, but also with his stern uncle, his cloistered cousins, his sympathetic aunts, and the ghost of his cousin, a drug war victim, that he confronts the question, What right do I have as a stranger to even remotely think about solving a problem entrenched in a place that I’m not allowed to consider home?

Ribay’s stance is he needs to speak about injustices like the drug war, hence The Patron Saints of Nothing.

“Working on the story kind of solidified that not only do I have the right [to speak against these injustices] but also that I need to. When people don’t speak out and pay attention to what’s going on, it allows it to continue.”

Writing the book, he said, was also an exercise in showing his love for his community, writing about it “filled with so much love but at the same time [acknowledging] the things that are wrong.” He said he always strives for this balance in his fiction. “That’s always something that’s I’m striving for…showing and expressing a love for the community or the place, without romanticizing it or glossing over the negative aspects.”

And so Ribay, through Jay, says: “It strikes me that I cannot claim this country’s serene coves and sun-soaked beaches without also claiming its poverty, its problems, its history. To say that any aspect of it is part of me is to say that all of it is a part of me.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.