SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

One of the mother figures who raised me was an aunt from Zamboanga. My childhood memories are colored with bits of Chabacano used around the house and loving recollections of her hometown. Being born and raised in Manila, these stories of Zamboanga made me feel close to the city, even without having been there.

It was only in 2020 that I was able to try Chabacano cuisine. As the burnt coconut smokiness of tiyulah itum and the sweet spiciness of sambal soup blossomed in my mouth for the first time, I couldn’t help but wish I had known about these flavors sooner. It reminded me of my hometown – I was stuck in the bubble of Metro Manila, and I needed to go beyond it to learn more about the richness of our country’s cuisines and cultures.

Sadly, with the pandemic, my dream of traveling around the country and eating to my heart’s content is shelved for now. Luckily, I was able to chat with food historians and chefs who widened my understanding of Filipino food – from the significance of our geography to the limited resources available in our environment. From these factors arose the various food experiences and preferences that make up our cuisines – after all, each household can serve a multitude of ways to cook adobo or sinigang.

Join me in my journey of making sense of the cuisines around the country and discovering how our food’s diversity came to be.

What can studies tell us about the ways we eat?

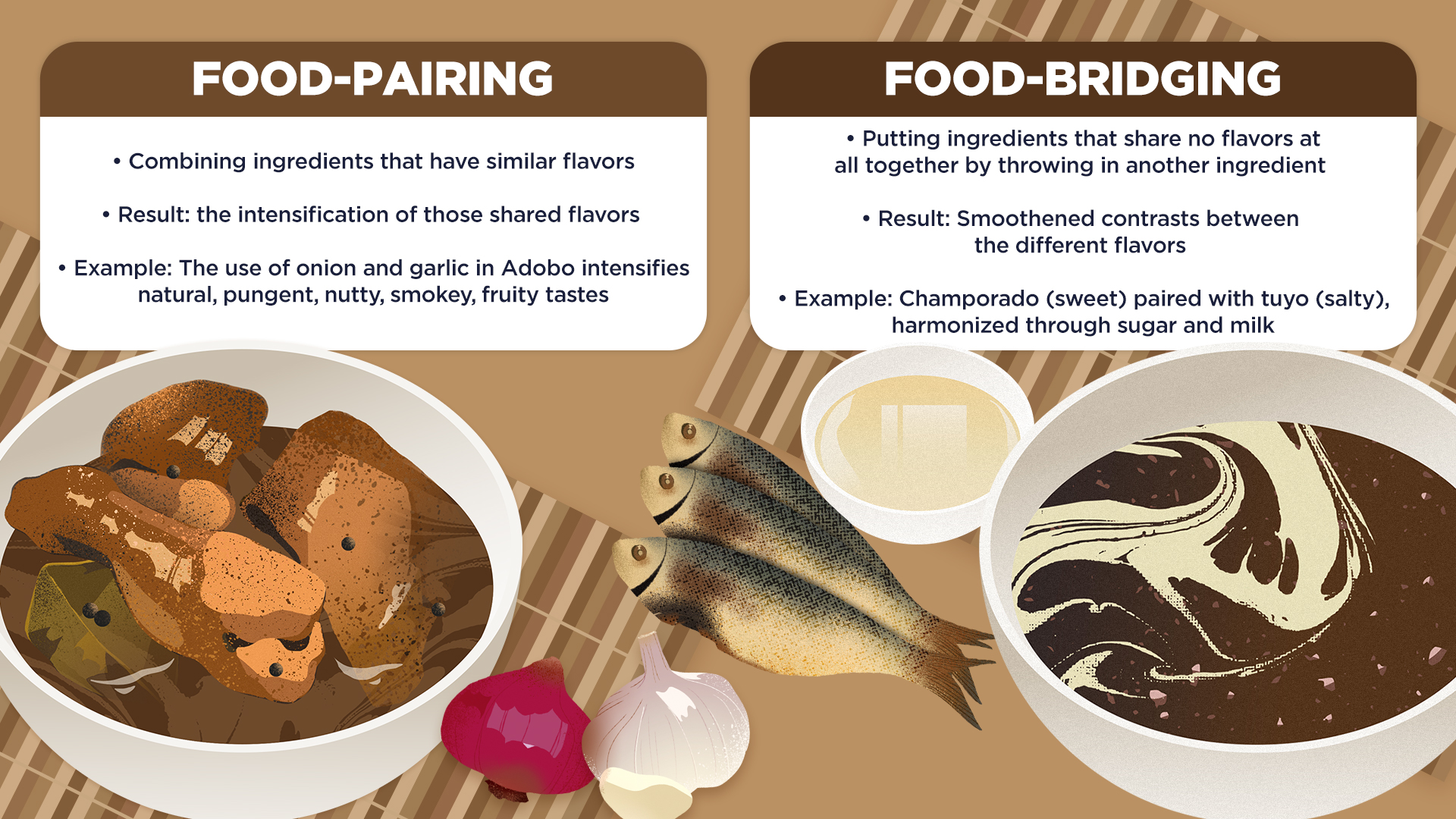

During my internship at Rappler, I learned about an interesting study where researchers in the field of network sciences scanned through over 50,000 recipes from cuisines around the world. As they observed how flavors were combined in these recipes, they also shed light on the most common ingredients that make up regional cuisines. The researchers then introduced flavor patterns they called food-bridging and food-pairing.

These patterns of food-bridging and food-pairing were also seen across the world in geopolitical groups: particularly, the cuisines of Southeast Asia, which apparently practice more food-bridging.

The findings show that there are statistically significant flavor patterns in our recipes which transcend cultures and individual tastes, manifesting differently from country to country. They also tell us a lot about how we choose the ingredients we combine in our food according to flavors and textures.

In the bigger picture, I also found it interesting that these kinds of studies show how data and science can be used to learn more about ourselves culturally. Merging the precision of science and the organic nature of food, the ideas of flavor pairings pave the way for culinary innovations and creativity too.

Food-bridging and food-pairing in Filipino cuisines

Thinking about the colorful cuisines of Southeast Asia, let alone our country, I explored the food-bridging and food-pairing theory in the Philippine context. It was interesting to learn that, locally, these flavor patterns seem to occur not just in how we combine flavors but also in how we form entire dishes.

Through her extensive studies on Filipino recipes, food historian Felice Prudente Sta. Maria conjected that food-bridging may be evident in how we personalize meals.

“The only pre-colonial meal on record served roasted fish accompanied by freshly harvested raw ginger. Rice (presumably plain) was also served. So the fish (that may have been roasted without any seasoning or leaf wrapper) acquires the piquancy of ginger (likely white),” Prudente shared with Rappler over an email.

She also mentioned champorado and tuyo as an example – as the bitterness of cacao is countered by sugar and milk, and then paired with the saltiness of tuyo. These flavors, according to Prudente, work harmoniously together.

Over a call with Rappler, Amy Besa, writer, chef, and co-owner of Purple Yam in Brooklyn and Malate, stated that food-pairing is also a common practice in Filipino culture. Through her own experiences and conversations with Filipino customers on their fondest memories of food, she observed that food-pairing occurs in the ways we put dishes together, citing combinations of contrasting food like ginisang monggo and bangus.

However, as the studies of food-bridging and food-pairing were written by foreign researchers, she noted that they may not completely understand the nuances of Filipino cuisines, as ours differ from culinary practices in the west.

In another call with Rappler, food writer and book designer Ige Ramos supported the idea of food-pairing in our culture, sharing how he would eat terno-terno and tono-tono style back in his hometown Cavite. To eat terno–terno and tono-tono means to match food according to textures, tastes, and colors, creating a meal that’s in tune.

Ramos mused about a food combination called Tres Marias that he enjoyed with his family on Sundays: it comprises of kare kare with tripe and oxtail paired with its ka-terno, kilawin papaya (grated green papaya with roasted and pounded pancreas, cooked in vinegar and miso). To complete the triad, chicken or pork adobo seka (a dry type of adobo) would be served as well to complement the wetness of the first two dishes, resulting in a tono-tono or in-tunemeal.

Flavors in our food, flavors from our land

The diverse Philippines is home to countless crops and wildlife. With this, geography plays a significant role in the extensive variation of Philippine cuisines.

As our ancestors arrived and settled into the thousands of islands across the Philippines, the natural resources available to them varied depending on the location. Consequently, Philippine cuisines and flavors continue to evolve according to the ingredients accessible to people in their environments. Yet, while each region boasts of different resources, certain ingredients and flavors still prevail across the country.

To find the most basic flavor profiles of our cuisines, we can begin by looking at the country’s topography.

“If you’re looking at flavor profiles in the Philippines, the first thing you have to do is look at the map. I say that to every single person who has any interest in food,” Besa shared.

With the Philippines’ coastline running 36,289 km – one of the longest in the world–it follows that salt and seafood are major flavors of Philippine cuisines. We can see this in our kinilaw, a preparation method involving raw seafood marinated in vinegar that’s existed since ancient times. Before all these foreign influences came into the picture, our ancestors were already experimenting with how to consume fish.

Considering our country’s tropical climate as well, our environment thrives with a wealth of coconuts, tropical fruit, and palms – all containing sugar or sap that naturally ferments and turns into vinegar. With the abundance of vinegar in our country, naturally, sourness became a major flavor in our cuisines as seen in popular dishes like adobo.

Regionalization of dishes

Geography also affects the formation of cultural preferences in our food. According to Besa, it has always been up to each locale’s communities to choose or reject ingredients found in their environments. These choices lead to a mastery of the natural flavors available to them, cultivating the ways they cook and the flavors they produce in their dishes.

Historian Ambeth Ocampo, who has studied and written extensively about Filipino culture and food, seconded this interplay of geography, available ingredients, and cultural preference in regional cuisines.

“For instance, rice is the staple but the way it is cooked and presented differs…” he illustrated in an email to Rappler. As another example of this interplay, the distinguished spiciness of Bicolano cuisine and their generous use of siling labuyo can be attributed to the abundance of siling labuyo bushes in the region. Complementing the spiciness of chili, coconut milk or gata is also a staple of Bicolano food as coconut is a major crop of the region.

Along with geography, Ramos notes that the movement of ethnolinguistic groups around the country also shaped our cuisines.

“So let’s say you’re from Zamboanga and then you migrated to Manila, and you have your regional food with you. Sometimes you don’t get the proper ingredients because they are not available or don’t exist in the community you’ve moved into. You have to adapt. That’s how food changes,” he shared in a mix of English and Filipino.

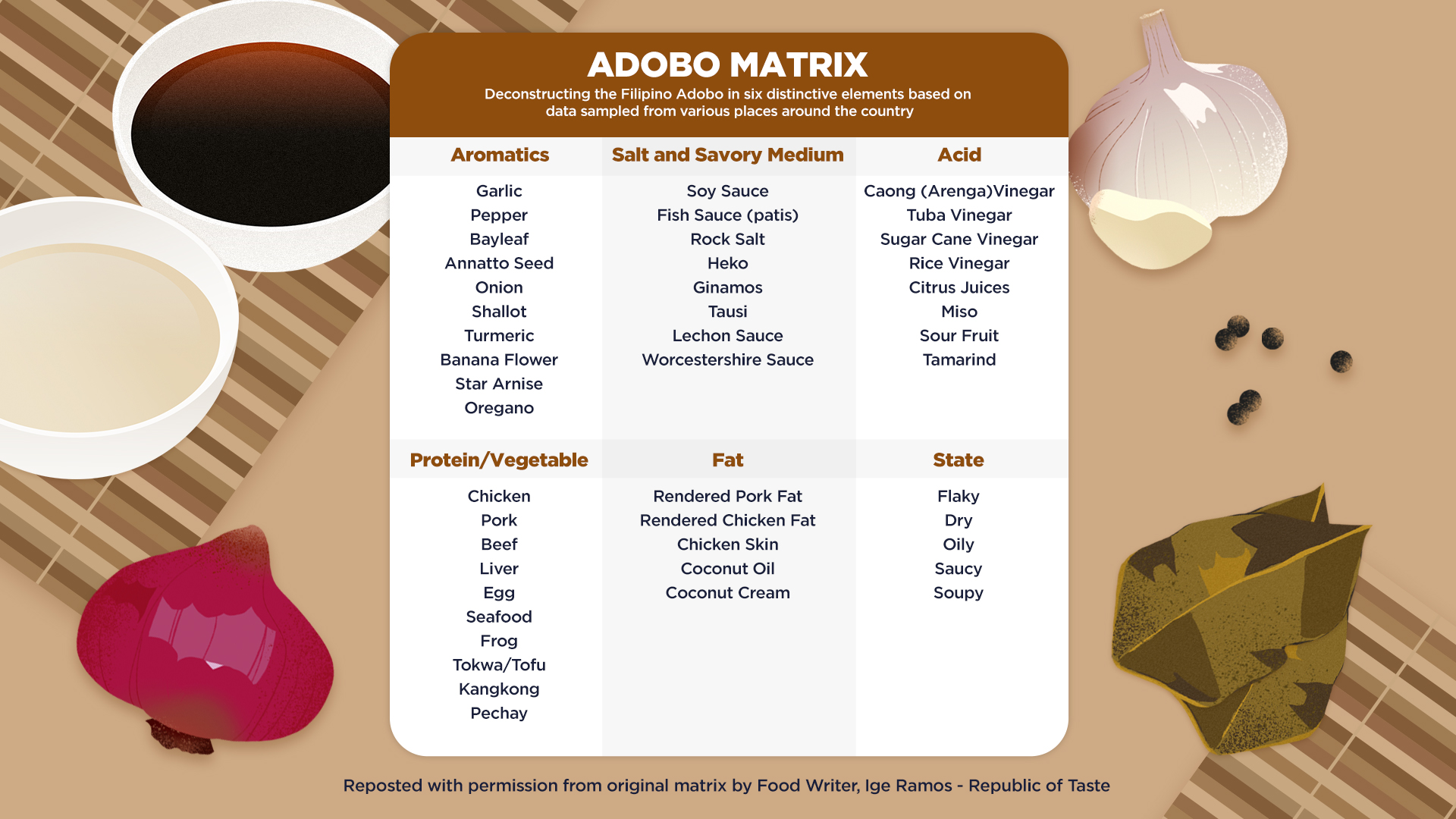

Our cherished adobo alone can tell us of the diversity of flavors, preparation methods, and ways of eating per region. Ramos created a “deconstruct” distinguishing six basic elements of adobo: aromatics, salty and savory mediums, acid, proteins or vegetables, fat, and the texture of the adobo.

Ramos’ Adobo Deconstruct conveys that adobo can be anything when these six essential elements are present.

With the great number of ingredients and resources available around the country, it’s no wonder that there are countless variations of the beloved dish. Even one household alone can most probably conjure different types of adobo, as every Filipino has their own way of preparing it. – Rappler.com

Tamia Reodica is a former marketing intern at Rappler. She dabbles in visual arts, music, and writing.

Special thanks to:

- Amy Besa, writer, chef, and owner of Purple Yam in Malate and Brooklyn with husband Romy Dorotan

- Felice Prudente Sta. Maria, food historian, writer, and heritage advocate

- Ige Ramos, food writer and book designer

- Ambeth Ocampo, historian, writer, professor

- JP Anglo, chef and owner of Sarsa restaurant with wife Camille

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.