SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

A local fashion glossy recently published a short piece on Filipina actress and entrepreneur Nadine Lustre. The author describes Lustre as an “outspoken champion of Filipina morena beauty,” mentioning instances where the actress shut down critics who were giving her “a lot of hate for being dark.” In the same space, however, the author writes off Lustre’s complexion as both a flaw that should be “embraced” and a “new thing.”

That a celebrity with the status of Lustre would still be criticized for her skin color shows a well-documented dominant preference for whiter skin, confining the definition of “beauty” – at least as far as the entertainment and fashion industries were concerned – to those with mestiza features. The term mestiza had previously just referred to those “of mixed race,” but was later embraced as a signifier of social capital, signifying a prevalence of internalized colonialism among Filipinos.

Despite the article’s petty and superficial nature and its easy dismissal as “fluff,” it still imparts an uncomfortable truth: that beauty is an enduring concern. As an industry, beauty is worth billions – far more if we were to include adjacent industries like fashion, fitness, and wellness. Even as beauty continues to be diminished as mere frivolity (and this is undoubtedly due to its historically gendered nature as “women’s work”), Filipinos, more often than not, deeply care about appearances. Or rather, we are conditioned to.

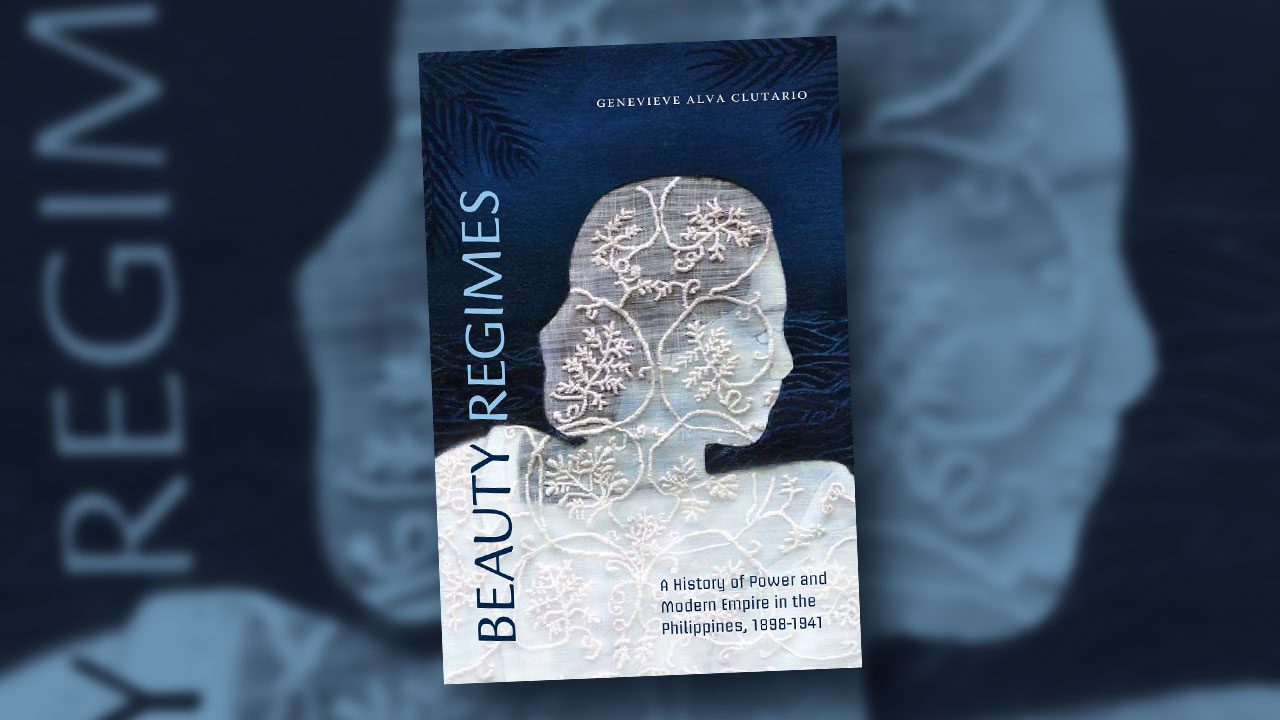

Genevieve Alva Clutario’s Beauty Regimes: A History of Power and Modern Empire in the Philippines, 1898-1941 (Duke University Press, 2023) picks at the threads of this seemingly petty yet ubiquitous concern to unravel a history of beauty production. By confining her study to the periods wherein the budding Philippine nation was being handed from one regime to the next, she delivers a sharp analysis of how gender, more specifically the performance of Filipina femininity, was racialized and disciplined to serve the social and economic demands of modernity under a period of “transimperialism,” or overlapping colonial regimes.

In a nutshell, this makes Beauty Regimes “the untold story of beauty work and empire,” linking two seemingly disparate concepts across five chapters (and one long epilogue) where Clutario tracks emotional, physical, and financial investments in Filipina beauty production. More generally, Clutario asks, “What can we gain by taking beauty seriously?” against a backdrop of shifting power structures, moving from the deeply racist change of hands from the Spanish to the American colonial administration, to the brutality experienced under the Japanese military.

Beginning each chapter with a seemingly innocuous anecdote, she connects seemingly irrelevant beauty talk to broader phenomena, thereby charting the formation of her titular regimes and the larger system they uphold. While this might sound like a narrative of the beauty and fashion industries within Philippine economic history (in itself, a worthwhile endeavor), Clutario takes it a step further, describing not only the formation of beauty businesses, but the role of both paid and unpaid beauty work within mounting class and racial tensions between Filipinos and the different empires that subjugated them.

Peering through a gendered lens, Clutario exposes the complex roles Filipinas played within empire and the fraught establishment of the Philippine Commonwealth, building upon previous works on Philippine-American relations, such as Elizabeth Holt’s Colonizing Filipinas (2002), Nerissa Balce’s Body Parts of Empire (2016), and more recently, Stephanie Coo’s Clothing the Colony (2019), all of which were published by the Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Despite confining the text to a specific period, Clutario’s work is made more relevant by an enduring anxiety over the embodiment of a Filipino identity, i.e. Who gets to be called a Filipino/a/x? This is exemplified by the nostalgia peddled by accounts like @fashionable_filipinas on Instagram, which celebrates (deliberately or otherwise) some notion of Filipina quintessence, particularly around the wearing of the butterfly-sleeved terno – an outfit which, lest we forget, was weaponized by a deposed dictator’s wife in her own attempts at monopolizing the discourse on the good, the true, and the beautiful.

What Clutario makes glaringly obvious (especially in chapters one and five) is that an outfit, as in the case of the butterfly-sleeved terno and numerous other finery donned by Filipina elites, is never just an outfit, just as beauty belies far more than surface and artifice. Writing about the wives of politicians, embroiderers, beauty queens, and socialites, Clutario renders beauty as a complex weapon. In the hands of her Filipina subjects, it is deployed with both tenderness and aggression.

In chapter two, Clutario lays out the origins of the country’s well-known beauty pageant industrial complex, where she points out how beauty still allows Filipinas and Filipina-identifying subjects to crown themselves “queen for a day.” Beyond the already familiar criticisms of Filipina participation in the pageant world, Clutario’s work also points to a more contemporary phenomenon: where the beauty pageant is also a venue for self-organization and empowerment – a means for Filipinas to carve out space for themselves in a world they otherwise had no hand in making. This brings to mind the recent breakthroughs of the Pinoy drag scene, and other spaces celebrating queer joy.

The optimism of this chapter however is brought back down to earth in the next sections, where Clutario veers away from embodied performances of beauty, and towards the establishment of export-oriented cottage industries in the Philippines. Across chapters three and four, she describes the growth of a work force of Filipina embroiderers, utilizing child labor through the colonial public school system, as well as prison labor, through the women’s wards in Bilibid penitentiary. Clutario makes the disturbing observation of Filipinas’ “appeal as a cheap, feminized labor source…grounded in their colonial status and nonwhite racialization, which together forged a disposable and vulnerable worker identity that persisted long after the formal end of US colonial rule (116).”

This may prompt readers to consider Beauty Regimes not only in light of the fashion and beauty industries, but for the role of the Philippines in the global export of care labor and, by extension, the country’s continued dependence on outsourced labor, both internally and internationally. These descriptions still apply to how much of internal migration is still driven by Filipinas moving from the provinces to the cities, to work in the homes and families of wealthier Filipinos. On a larger scale, this is seen in the number of Filipinas (1.10 million, as of 2021) who continue to perform similar roles abroad.

By deftly articulating these connections between economic vulnerability and beauty work as a performance of so-called feminine roles, Clutario exposes the interwoven histories of empire and aesthetics. She thereby exposes the insidious ways that beauty – and by extension, femininity and discipline – was used to shroud broader systems of oppression and exploitation. – Rappler.com

Beauty Regimes: A History of Power and Modern Empire in the Philippines, 1898-1941 is forthcoming from Duke University Press.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.