SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This win was supposed to be a triumph.

Louise Glück is the first American woman to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 27 years, the last one being Toni Morrison (though historically, women have consistently swept that particular Nobel category.) And when news came out that the famed lyric poet was getting more gold on her already prestigious name, I and many other contemporary writers who grew up loving her work professed abundant praise. Grand matriarch of the lyric, manipulator of myth, author of The Wild Iris, who makes omens of small flowers.

But this is 2020, and the Bad Year Bingo Card always has one square that goes “your hero says something racist,” and that’s just what Glück does.

In her acceptance speech, Glück references two pieces as inspirations: the poem The Little Black Boy by William Blake and the song “Swanee River” by Stephen Foster. Blake straight-up takes the persona and voice of a black boy in his poem, in a way that tries to be empowering, but frankly falls flat on his face. Stephen Foster was a musician who, during his career in the 1800s, composed songs for the blackface minstrel show tradition, a genre of American entertainment that disparaged black people.

You read her speech and you wonder how it doesn’t occur to Glück that her words sabotage themselves, failing to read the room of 2020. Peculiarly, articles that report Glück’s win leave this part of her speech out, highlighting her meditations on public perception and the poet’s private voice, and the supposed tension therein. Her edification of the racist baggage of American letters, and her take on what should be the primary preoccupation of the artist, seem like separate concerns, but are entangled.

And yet how silly it must look from the outside – petty drama, grist of the grad school rumor mill, poets lost in their puny worlds of aesthetic woo-woo. Elsewhere, I’m sure, a crotchety card-carrying member of the Old Guard bemoans how overbearingly sensitive young people are these days. Elsewhere, I’m sure, a daisy shakes off its last wilting petal, in disbelief of its own decay.

That’s kind of the throbbing heart of it all, right? The personal is always more than the personal.

“Interiority” is a buzzword whose ugly mug you’ll come across in conversations like this. Basically it refers to the internal life of a character, persona, or the author themselves – their thoughts, emotions, psychology, dreams, imagination, memories, trauma. When interiority is expressed poorly in a poem, it feels like empty navel-gazing. When done well, it feels like the universe experiencing itself.

Glück’s speech seems to have spurred some discussion on the pitfalls of interiority poetics, of which she is a master. The Swedish Academy will agree to that much, having rewarded Glück “for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal.” It’s a field of contradictions, to work with both the individual and the universal, and it is fraught with traps. One such trap is the thought that my existence is all existence, my life is the life that matters most to me, I touch the world and it becomes me. Navel-gazing.

(And not that it’s exactly the same, but I think of Ezra Pound, the imagist poet everybody knows of “petals on a wet, black bough” fame, who was also a fascist collaborator and ardent supporter of Benito Mussolini. He gets it wrong. He regards the earth, and disregards the human beings moving in it.)

I don’t think that a poet primarily working with the interior is the whole problem, but there’s something to be said about how an aesthetic disposition can affect the way you move in and through the world. In an interview, poet Angel Nafis describes the classes she took under her professor Maurice Manning about the tradition of the pastoral poets, for whom expressing interiority is part of the deal.

“These romantic poets, when they talk about nature, it’s their reckoning with the bigger questions. And that nature becomes a symbol. Right?” Most people understand this on an intuitive level, regardless of poetry. It’s why people love making beach trips, if only to let the sight of the sea’s sheer vastness overpower their cosmopolitan anxieties. It’s why you can look at a flower triumphantly bursting through concrete and inevitably project.”

“And so, then it got me thinking about how, talking about nature was like, you being on the utmost meticulous, and the utmost humble, and the utmost reverent of the big-ness of the universe?” Nafis continues.

“And now it might be actually, in many ways – the ways that we are exhausted with it, are the ways that people use it actually to flatten, and not talk about the world.”

This is the trap. When the individual becomes the universal, the social becomes irrelevant. What good is it to extract the spiritual worth of a sublime micro-moment, when such endeavors eclipse the rest of the world?

Obviously no one is saying that you can’t write a poem about just flowers, or you can’t carve out a space on a page where you can cradle problems that are yours alone. But it could be that Glück has tragically cornered herself into a vapid dichotomy, one that treats the interior world as a safe haven to be sheltered at all costs from the cacophony of our surroundings. But isn’t it the case that we are the sum of our experiences? Isn’t it that what forms who we are includes how sensitively we engage social ills greater than us? Manning and Nafis might mention that a poet who deals with interiority, nature, the individual, the universal, whatever, must work within a “mode of emphatic noticing.”

You’re allowed to look within, but you have to gesture outwards. To put it more simply, it’s not always about you.

I’m certain that Glück is cognizant of the criticisms she’s getting, and mentally doubling down on one of her speech’s points: “I am talking about a temperament that distrusts public life or sees it as the realm in which generalization obliterates precision, and partial truth replaces candor and charged disclosure.”

As if collective uproar can only be noise. As if the song of public outrage can only be off-key. As evidenced by the tone-deafness of her speech, Gluck may have misconstrued her inner world as a transcendentally human experience, without considering her subject position as, well, a white person, institutionally championed by the academe no less.

At this point, I shouldn’t be surprised at the fact that there is no writer, no artist so skilled that they are immune to making an ass of themselves (J.K. Rowling fans, however, have been living with this hard truth for a while now). I’ve seen and heard of poets who, in the wake of a typhoon that happened the day before, or while the collective grief of an extrajudicial killing is still raw, hop straightaway to their aesthetic clownery to post a tawdry stanza on Facebook. I’ve seen otherwise reasonable and gifted minds swat away the actions of dictators and imperialists. For them, the world is nothing more than a resource from which to extract another pithy couplet. They move through the world and leave dead flowers in their wake. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

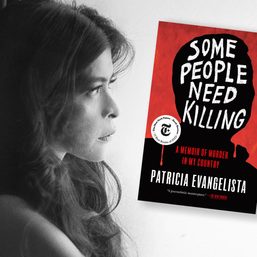

![[Rappler’s Best] Patricia Evangelista](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/unnamed-9-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=486px%2C0px%2C1333px%2C1333px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.