SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

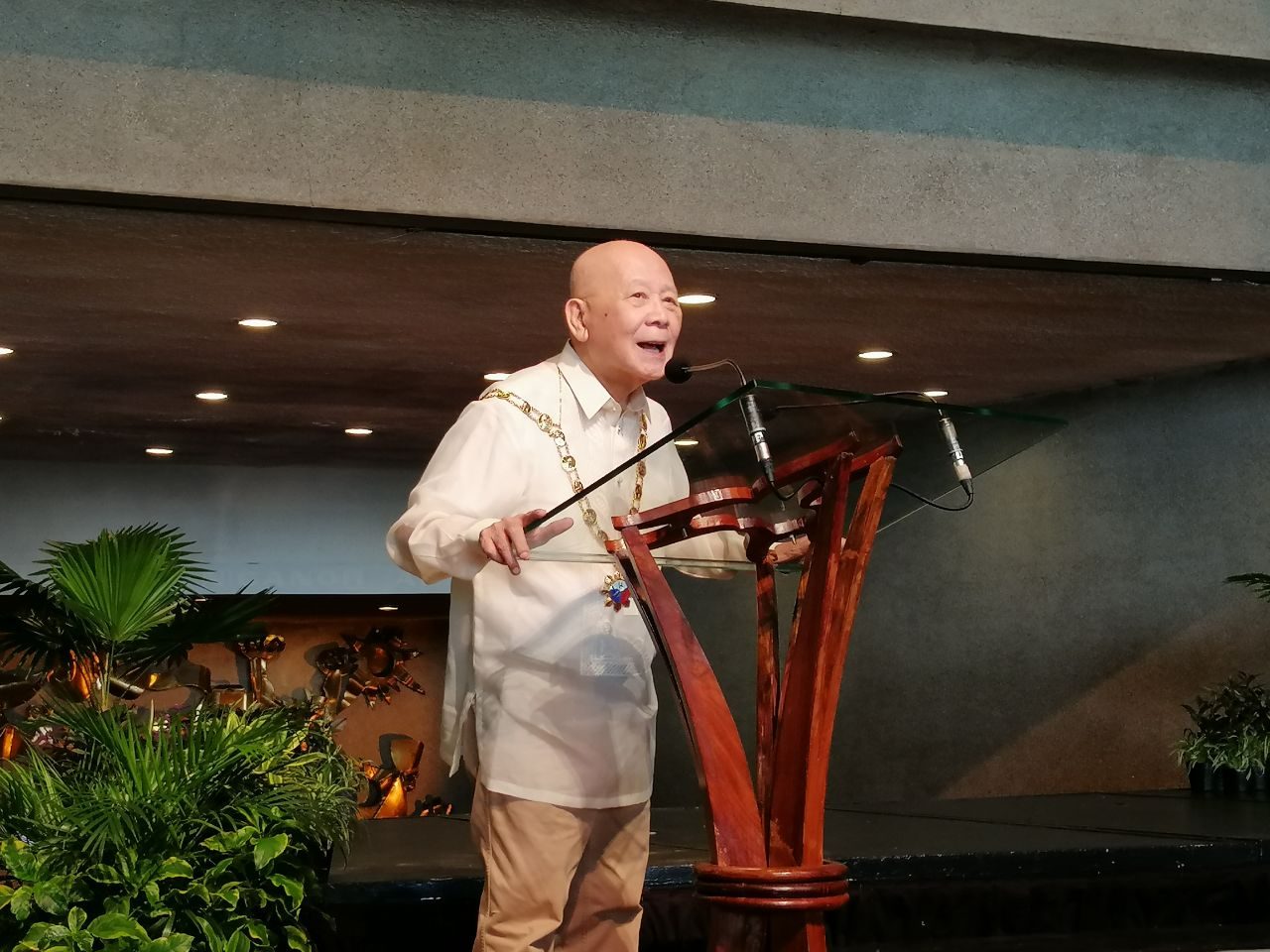

Bienvenido Lumbera, the writer and poet who died on September 28 at age 89, led a life that was marked by a love for country, and a belief that writing must be done in service of the community.

Lumbera was born on April 11, 1932 in Lipa, Batangas – a place whose rich history helped shape his work and foster his love for country.

“Dahil ang Lipa ay may mahabang kasaysayan sa mga kwento ng mga nakatatanda na mga alalala sa mga pinagdaaanan ng bayan, natanim sa aking isipan na ang aking nilakhang lugar ay mayroong kasaysayan at nais ko sana magkaroon ng bahagi dun sa kasayayang iyon,” he said in an interview in 2011.

(Because Lipa has a long history in the stories of those who remember what the country has been through, it’s been implanted in my mind that my hometown has a history, and I want to play a part in that history.)

Orphaned as a young boy, he was raised first by his paternal grandmother, and later by his godparents, Enrique and Amanda Lumbera, who he chose to stay with mainly because they could send him to school.

American dream, Filipino identity

When it was time for him to enter college, he only knew of the University of the Philippines and was ready to enroll, but his godparents said that the university’s Quezon City campus was too far for them to visit when they’d go to Manila to do business in Divisoria.

He then wound up at the University of Santo Tomas (UST), where he took up journalism. After graduating cum laude from UST, he returned to his hometown where he taught high school english at his alma mater, Mabini Academy – his first teaching job.

He left the teaching post mid-year to pursue an editing position at a local Subic paper, though he was fired after two months. While dipping into odd writing jobs, he applied for a Fulbright scholarship, and went on to earn an MA and a PhD in Comparative Literature from the Indiana University in the United States.

“Nag-aaral palang ako sa UST, ang aking pangarap ay makarating sa Estados Unidos, at doon makapagaral,” he said.

It was in the United States that Lumbera said he filled the gaps in his cultural education, which he felt had been lacking. He did this by watching films, plays, opera, listening to jazz music – “lahat ng mga bagay bagay na itinuturing kong mahalaga para sa isang manunulat na kinakailangan magkaroon ng maraming karanasan sa larangan ng kultura (everything that I believe is important for a writer who needs to have many cultural experiences),” he said.

For his dissertation, he initially turned his focus on Indian fiction in English, until a fellow Filipino student asked him why he wasn’t writing about Filipino literature instead.

“Nabuksan yung isip ko na, aba, yun nga palang aking pag-aaral ay dapat iukol ko sa mga bagay bagay na may kinalaman sa Pilipinas,” he said.

(I realized that my studies should be focused on things that are related to the Philippines)

He then decided to write about Filipino literature, particularly poetry written in Tagalog.

After completing his dissertation, he took up a teaching post at Ateneo de Manila University, where he later revolutionized the curriculum from the inside out, together with his friend, fellow poet and later National Artist Rolando Tinio. The two professors revised courses to include Filipino material, and compiled readings that contained essays about the Philippines. They also did away with English-only policies, giving lectures in Tagalog and encouraging students to use the language.

For the people

As a professor at the Ateneo, Lumbera’s activist spirit stirred. As a facilitator for the university’s spiritual group Days With The Lord, he ended up counselling troubled students. Doing so, he said, made him realize that he wanted to do the same, but for those who were less privileged.

“Bakit ba ako dito sa mga kabataang mayayaman naghahangad makatulong?…Naisip ko, mas dapat iniukol ko ang aking panahon sa mga karaniwang mamamayan, mga mamamayan na walang access sa mga luxuries, sa mga aktibidad ng mga mayayaman,” he said.

(Why am I giving advice to these rich kids?…I thought I should dedicate my time to ordinary citizens, those without access to luxuries or activities for the rich.)

His activism was challenged when dictator Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in 1972. As the leader of a group for activist writers, Lumbera knew he would be targeted. He went into hiding, and later went underground.

He stayed in a UG (underground) house, and there put his literary prowess towards editing a publication that aimed to challenge the Marcos ideology “na nagpapanggap na makabayan subalit na tunay na mapaniil ang kanilang patakaran (pretending to be for the country, but having truly brutal policies).”

He was later caught, arrested, and detained for almost a year by thhe military.

When he was released, he admitted feeling sad because he would be separated from his fellow dissidents, and his life on the inside was so different from the world outside.

He recalled an instance after his release that particularly struck him – when he saw models as live mannequins in a department store window. For him, they embodied what life was like under martial law.

“So nandun sila, nakadisplay sila, alam mong buhay ang mga taong ito pero hindi sila nakikipagusap, hindi sila gumagawlaaw. Ang laki ng epekto nung sa akin. Naiyak ako at itong mga tao na ito na tunay na tao pero nagpapanggap na hindi tao, parang ganun ang sitwasyon sa panahon ng Martial Law sa paningin ko,” he

(There they were, on display. You knew these people were alive, but they weren’t speaking, they weren’t moving. That really affected me. I cried for these people that were real people but were pretending not to be people, that was what the situation was under martial law, I think.)

Oddly enough, it was at a government agency that he found work after his detainment – at the Department of Public Information, where he became editor of the magazine Sagisag.

He also returned to the academe. He was set to return to Ateneo where he already had tenure and where Tinio – by then head of the university’s Filipino department – already had a post waiting for him. The dean, however said he could not return, due to his pre-martial law activities. Lumbera then ended up at the University of the Philippines.

Freedom

After martial law, Lumbera had to find more creative ways to write about his beliefs, to avoid persecution from the military.

“Kwan yan eh, parang ‘betrayal of yourself’…halip na ikaw ay tahasang magtaksil sa iyong pinaniniwalaan, umiisip ka ng paraan upang maigiit pa rin ang iyong mga ideya bagamat alam mong nanganganib ang iyong buhay kung ikaw ay lubusang maglalantad ng iyong paniniwala,” he said.

(It’s like a ‘betrayal of yourself’… instead of completely abandoning your beliefs, you think of ways to stress your convictions even if you know your life is in danger if you outright speak about your beliefs.)

This led him to writing the libretto for the play Tales of the Manuvu – a ballet by choreographer Alice Reyes.

“[Lumbera] plumbed the script for something relevant and found the image of a caged bird yearning to break free. In his libretto for Tales of the Manuvu, he used this image to emphasize ‘the need for people to rely on themselves instead of relying on fate, or powerful men,’” wrote James R Rush in a profile on Lumbera for the Ramon Magsaysay Awards, which was conferred to him in 1993.

“Sometime later, when he learned that a military man had complained about the show’s political content, Lumbera was delighted. ‘I did not think that anybody saw my message,’” Rush wrote in the profile.

Tales of the Manuvu is among Lumbera’s best known works, which is fitting for a writer who professed being interested in theater ever since his early days as a professor – an influence of Tinio’s, he said. He also wrote the librettos for the plays Rama Hari, Bayani, and Hibik at Himagsik nina Victoria Lactaw.

The period after his release was a prolific time for Lumbera, who dabbled in all forms of literature, from poetry, to essays, to literary criticism.

The citation for his Ramon Magsaysay Award described it as “years of startling productivity,” where Lumbera published several award-winning books, was an active presence in literary circles, and wrote introductions to books by his colleagues and friends.

“As a teacher he mentored a new generation of literary scholars imbued with his own love for the country’s rich artistic traditions and languages,” the citation read.

From the day he refocused his dissertation to study Filipino instead of foreign literature, Lumbera had been enamored by the role language plays in building nationhood. In his Ramon Magsaysay citation, he is quoted as saying that “As long as we continue to use English, our scholars and academics will be dependent on other thinkers.”

He was fittingly named National Artist for Literature in April 2006, and the distinction could not be truer for Lumbera, who wrote plays, poems, essays, and stories in service of the nation – even if, at some point, it came at great personal cost.

As much as he will be remembered as a writer, it was his role as a teacher that Lumbera cherished above all else.

“Guro ako. Ako ay isang teacher (I am a teacher), primarily. Whether I’m writing a play or writing a poem, above all, ang importante sa akin, may estudyante ako na kinakausap tungkol sa panitikan, tungkol sa kultura ng mga Filipino (what’s important to me is that I have students I am speaking to about literature, about Filipino culture),” he said. “ That’s how I wish to be remembered, as a teacher.”

Whether as teacher, writer, poet, or dissident, Lumbera has left an indelible mark on Filipino culture, that which he championed throughout his life. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.