SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Habits, in a world pervaded by social media, have now been carved in hashtags. One hashtag in particular which has tried to create a habit of rebelling, if you will, in the Philippines is the #BannedBooksReadingChallenge, which asked people to post a video of them reading snippets from books deemed subversive by Philippine authorities.

The hashtag and the challenge began in November 2021, following an order from the Commission on Higher Education in the northern province of Cordillera to have books delving on communism – which could range from those penned by Karl Marx to those by Jose Ma. Sison – removed from libraries.

But it is not only in the Philippines where books are being banned in this day and age. On December 2, 2021, the writers’ organization PEN America decried the decision of the Leander school district in Texas to ban 11 books from libraries, including “The Handmaid’s Tale The Graphic Novel” and “V for Vendetta,” also a graphic novel.

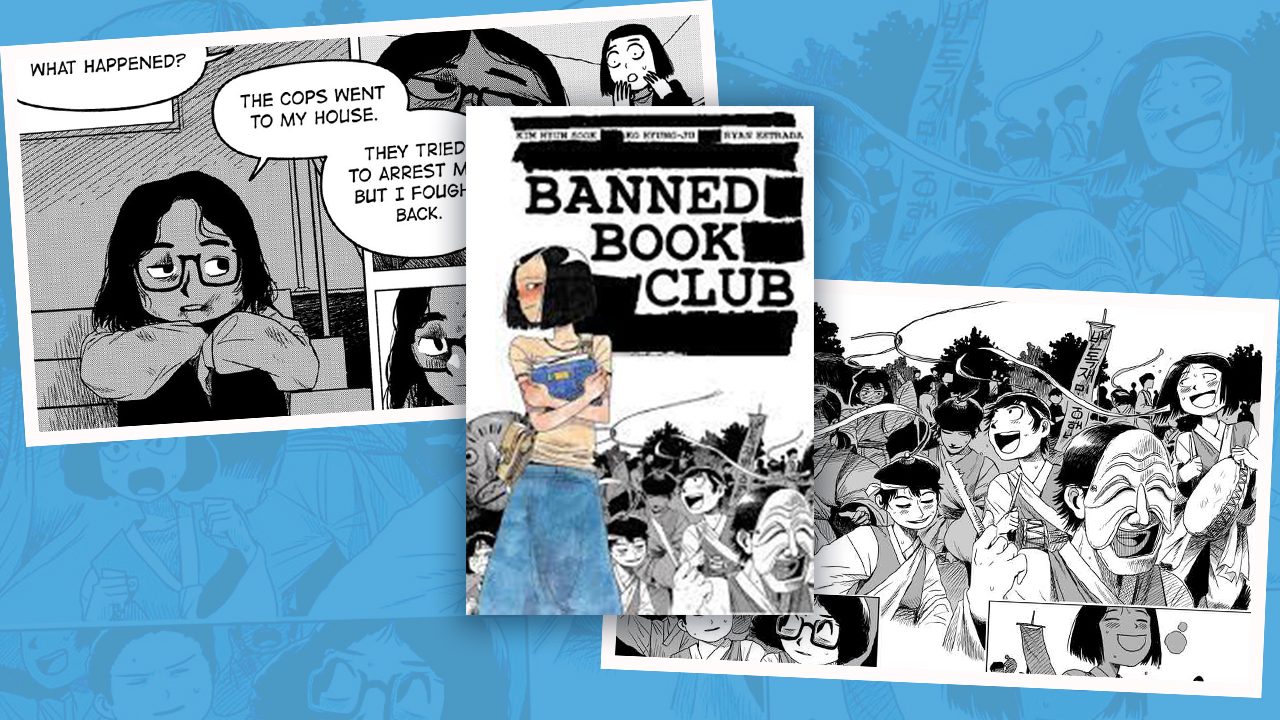

That this is happening now makes the story of another graphic novel – Kim Hyun Sook and Ryan Estrada’s “Banned Book Club” – more relevant than ever. Published on May 19, 2020 by Iron Circus Comics and based on Kim’s own life, the book spoke loudly to those whose defiance is marked by reading what the government doesn’t want them to read.

What makes “Banned Book Club” one for the books, pun intended, is that the graphic novel is a critique of South Korea’s political history as much as it is a tribute to friendships, youth, and familial bond.

The memoir introduces us initially to an apolitical protagonist, Hyun Sook, who just wants to finish her studies in a university. The fact that she even got to enter one is a big deal already for the young woman, who came from a family who tries to get by with what their small steak restaurant earns.

Through circumstances that are far from fortuitous, the English language and literature major would find herself pulled into a book club like no other, however. Cajoled by Hoon, a law student she met in a dance performance-cum-protest, she was shocked to learn that in their first meeting, they would discuss books like The “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” by Paul Freire and “The Cry of the People and Other Poems” by Ji Ha, who opposed the dictatorship of Park Chung-hee, South Korea’s ruler for 18 years.

The catch is that reading these books could put one behind bars. This is because Hyun Sook’s journey into the world of words which the state aims to invisibilize happened in the 1980s, at a time when students were at the frontlines of fighting the regime of then President Chun Doo-Hwan. Chun, who died at 90 years old on November 23, 2021, was convicted for ordering the military to quell protests in Gwangju in May 1980, leading to the death of 200 activists.

Why Hyun Sook made the choice to stay and fight for the club will take the reader into a meaningful journey into South Korea’s complex struggle for democracy and the role that art played both as part of government propaganda and as the opposition’s weapon of resistance.

We would get to learn why during that era, movies with highly sexualized themes can be shown in cinemas, while foreign news programs are best screened covertly. We would also understand why books “about peace” should be hidden under the covers of a book about romantic love.

This distinction and discovery are relayed in dialogue that is rich with the humor and sarcasm of young people. The language of “Banned Book Club” is the language of young dreamers – idealistic, angry, wily, empathetic.

Hyung Ju-Ko’s illustrations make this language more resonant as they emphasize the expressions of the characters – the shock, the deception, the earnestness – they are all there, colorful in black and white.

As Hyun Sook’s engagement in the club deepens, the readers get to learn what motivated the rest of the club to stay too, and what made the founder, Yuni, start it in the first place. Their sacrifices, the strategizing to keep the club’s members safe, the hard decisions they had to make, would draw the readers into the psyche of a generation which aches for freedom from a government which brands them communists just because they question and oppose the abuse of power.

While the biographical novel is filled with rage, however, there are definitely moments of tenderness. Hyun Sook gets to learn about her father’s own misgivings in life and why, amid these, he does not regret anything. She also realizes that even as her mother appears to object to her decision to study, she really loves her and supports her unequivocally.

Other than these, we enter into the realm of first romances, of holding hands while on a trip with friends, of inquiries about who’s dating who. This is where “Banned Book Club” reaffirms that in its pages lies the plexus of feelings, sentiments, and reveries that belong most especially to the young.

There’s the inevitable signs of unraveling, though. Every battle waged would be tested, with the possibility of ending what has been started hanging like a perennial specter.

One by one, the members of the underground book club would suffer because they have been discovered to be reading the books they’re not supposed to even take a peek into – at least, according to authorities. Jihoo, the poet, gets arrested, while Suji, the mathematics major who “loves punching cops,” gets thrown out of her house by her own mother.

This point of the novel gives rise to issues of trust, as the members grapple with paranoia. It’s what happens to movements, or campaigns, or efforts to change the world and challenge the system – seeds of distrust could be planted by external forces and from that, creeping division could flourish, sprout.

It reminds us of how tricky and fragile defiance could be; as in every uprising, there is always the thorny question of who really is an ally, or foe.

“Banned Book Club” further establishes this by giving us an array of other characters which showed various ways of duplicity and duality – there is the member of the school paper, the professor who seemed keen to teach the transformative power of literature but has a really different agenda, and there is the government agent, called OK, who beats up the book club’s members but serves as a doting father too to his kid.

But amid the internecine caused by the onslaught of challenges and threats to their safety, the “Banned Book Club” members would eventually find a way to fight alongside each other again, united by a common enemy – Chun’s regime.

What makes “Banned Book Club” an important reading for the young is that it will teach them that pushing for change is a long game. After the Molotov cocktails, the run-ins with government authorities, and the fiery protests, chances are, things would remain the same. The monsters you want to defeat would still be there, only with a different name this time around.

The story does not romanticize the fight for a better government. This is the most crucial message one can glean from the novel, as it gives us a very realistic take on how reforms are achieved – it will take more than one try. The fight will falter, fizzle. Supporters, like despots, will come and go and could make a comeback again when you least expect it.

People will get tired. Cynicism will arise. Democracy will seem untenable. But as Hoon says, “Progress is not a straight line. Never take it for granted.”

Kim’s novel ends on the continuation of South Korea’s history. After more than 30 years, the members of the Banned Book Club would meet each other again at a certain point in the country’s political state when the expression of beliefs through art – from dance to films to books – is being stifled once more. It’s a different ruler with the same tactic.

But when history repeats itself, it just doesn’t include the re-emergence of an oppressor. It also includes the rise of a new generation and an expansion of energies, a unity of sectors and communities, to expel the said oppressor.

It includes Hyun Sook, Yuni, Hoon, Gundo, Suji, and Jihoo and all the lessons which leapt from the pages of books they have read and distributed in secrecy when they were still young students.

Looking at the Philippines’ situation now, it’s easy to assume that the banning of certain books will continue. If Kim’s lived experiences could be any indicator, however, there will always be another proverbial underground club who would make sure these books get to be read.

Kim and Estrada’s writing would tell us that reading is just part of a bigger, harder fight, but it’s an indispensable first step. So pick a book. Open it. Changing a country’s history begins with the turning of pages. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Who’s afraid of books?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/10/ispeak-whos-afraid-of-books-sq.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[OPINION] Defend freedom of thought! Hands off our libraries!](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/09/ispeak-libraries-1280.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.