SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Does our democratic subculture possess any traction to direct us as we head off to our second century?

Does our democratic subculture possess any traction to direct us as we head off to our second century?

While we call ourselves democrats, the assurance of the political tone with which it is expressed is not matched by intellectual coherence and practical outcome of what is being conveyed.

After more than a hundred years as a nation, we are still languishing with a third world per capita income where our economic future is still opaque to our political leaders and a better standard of living is still elusive to the majority of our people.

Why is this so?

For me this question is an instructive reflection on how our democratic version was constructed as a copy. As a copy, it is not just a copy but also a poor copy of the original. Our version is at least four-times removed from its source – the American Democratic Experiment whom the French philosopher Alexis Tocqueville characterized as uniquely favored by four kinds of conditions: the structure of its government, geographical accidents, historical accidents, and the culture of its people.

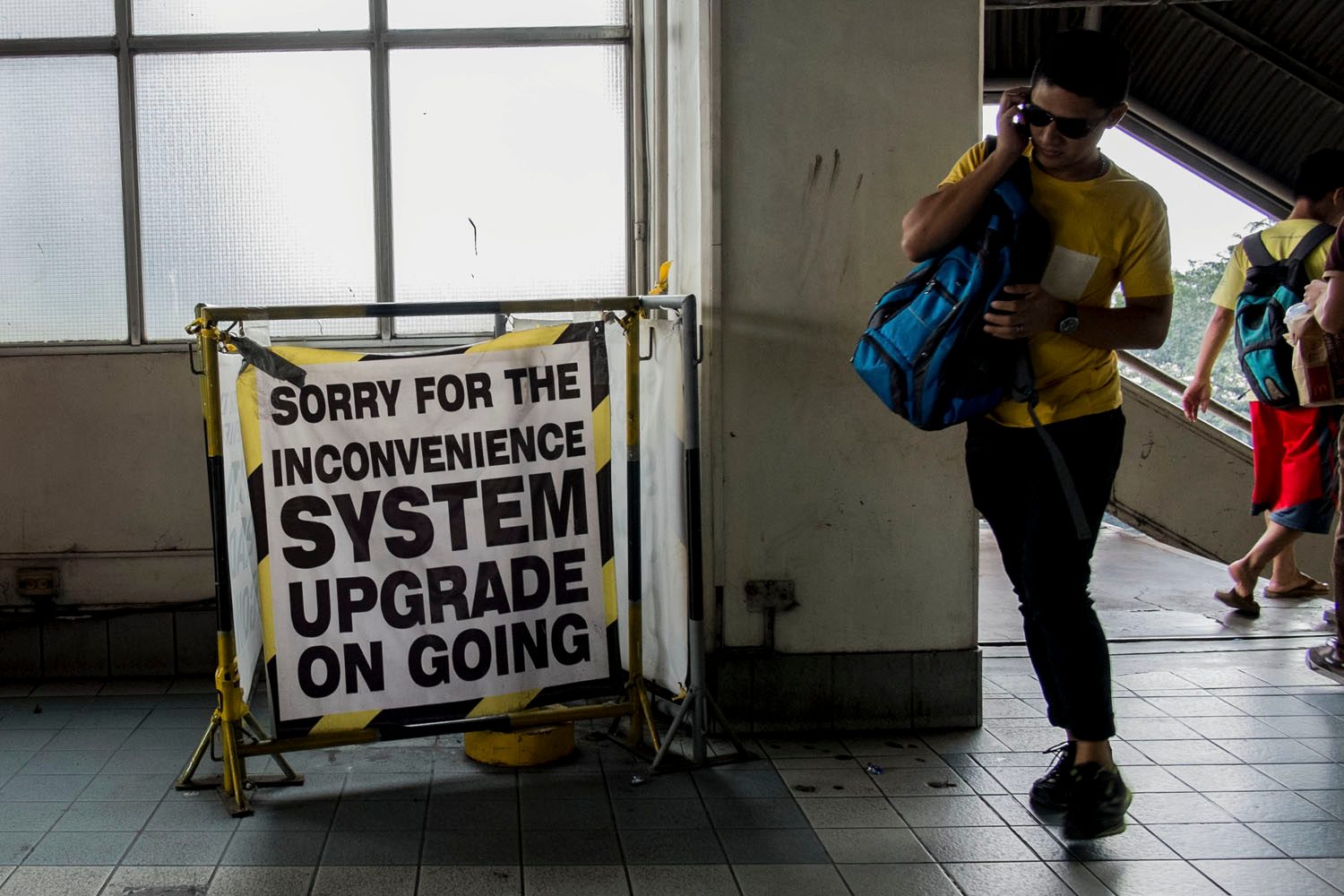

Lost in translation

As things now stand, we are lost in translation! We do not have America’s federal system aimed at promoting a serious local autonomy; we do not have the virtually empty continent of North America to expand; we do not have America’s general equality of wealth before its democratic government was established; and we do not have the strong hold of Protestantism in America which provided the ethics of the American Dream and the Town Hall Model of democratic self-government.

In contrast, we have a national cacique government which normalizes patronage and mendicancy; we have an archipelago stripped of its resources and subjected to a never-ending natural as well as political disasters; we have a structure of social inequality where the rich and poor coexist side-by-side wedged by a lattice of 10-foot concrete walls; and we have a dominant medieval religion which exacts a hierarchy of top-down obedience and conformity to sometimes outmoded beliefs and practices.

In the absence of those conditions, picture how far our image is removed from our reality. How then do we make sense of it? Why do we still make sense of it? Or can we really make sense of it? Like many of our compatriots, I mulled over these questions and our country’s prospect for a long time.

Our democratic version with its customary imperial praxis is a notion of misplaced sovereignty, especially given the fact that our commerce is global. The incongruence is obvious – our economic development is regional but our politics is still imperial.

Imperial bureaucracy

How can our democracy survive in an imperial bureaucratic setting that has no bearing whatsoever to a serious territorial representation? More so, a pork-barreled bureaucracy that is more responsive to favoritism than to transparency and accountability?

Over the years, I have come to the realization that our democratic subculture is fated to fail because it exposes the depth and breadth of our political mind as well as our political behavior.

Consider this: Despite the trillions of pesos that our imperial administrators had spent over the years on their respective ad-hoc and discretionary political priorities, we have not moved an inch beyond the politics of patronage. And worse, all we can show is how to squander and behave badly and then escape the just punishment for our actions.

Unless we do things differently, there is no way for us to salvage our democracy.

Where does my hope lie? My hope lies in the clear understanding of our natural and intrinsic strengths – three of which predominate: our archipelagic landscape conducive to maritime development; our geothermic proximity to the ring of fire as source of energy; and our highly educated gentry endowed with intellectual, technical, and organizational capabilities to succeed.

City-state planning

Against this backdrop, we can craft our country as a maritime society of territorial and functional city-states (either as city-provincial-regional-or-island-based).

By maritime society, I mean the re-rooting of our development to the origins of the city-state that the classical Greeks talked about. In fact, the success of Monaco, Macau, Hong Kong, or Singapore can be traced to the application of the city-state model of development. Future-wise, this model will prepare us better to face our naval challenges in West Philippine Sea.

Geographically, it is pointless to exhaust the cultivation of our limited land resource. Instead we must conserve it by making maritime trade and services as our chief economic activities. Unfortunately, our preoccupation with the former is the main reason why our people are still being fatigued by a never-ending agrarian conflict. And yet, land is not our main resource!

Crux of the matter

We can design a medium range or long range maritime master plan. But the crux of the matter is implementation. And not just implementation, but a no-nonsense, and a non-distracted implementation!

And who can do this? Here are some ideas.

First, we need an incorruptible strongman committed to the tasks of maritime development, no matter what.

Second, we must selectively replicate all over the archipelago special districts à la Subic Bay Metropolitan Area (SBMA) and Clark Development Corporation (CDC). If we do it right, this is the closest we can get to our city-state development model.

Third, we must restructure our country into honest-to-goodness programmatic and integrated territories. No more gerrymandering of political power via invented special interest groups or skewed representation of senators and government functionaries from Luzon at the expense of Visayas and Mindanao.

Finally, there is the easiest, and yet, the most painful option. We can simply maintain the status quo, romanticize our political atrophy, or render our people’s democratic chance a heart-breaking déjà vu.

Can we change our future for the better? Yes, we can. – Rappler.com

Efren Padilla is a full professor at California State University, East Bay. His areas of specialization are urban sociology, urban planning, and social demography. During his quarter breaks, he provides pro bono planning consultancy to selected LGUs in the Philippines. https://efrenpadilla.wordpress.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.