SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – It was a hum-drum Thursday afternoon at home. Vivian (not her real name) was scrolling through her Instagram feed and her boyfriend was strumming his guitar in the background.

“Here’s another one,” Vivian said. She handed her phone over to her boyfriend and showed him the post of one of their friends: “Palong palo ako now. Sarap ng feeling.” (I’m so high right now. It feels great.)

Vivian, 21, has been a full-time drug dealer for the last three years or so, selling “recreational drugs” like X (ecstasy), Fly High and its close cousin, Green Amore.

She sells through friends and friends of friends, online or at raves and music festivals. Boracay’s Laboracay is a natural magnet for dealers. According to Vivian, she has to hire “additional help” to meet the beach party demand.

Save for a few “hot” periods like the start of the War on Drugs when dealers laid low, raves and music festivals remain a popular selling place where demand and supply can meet.

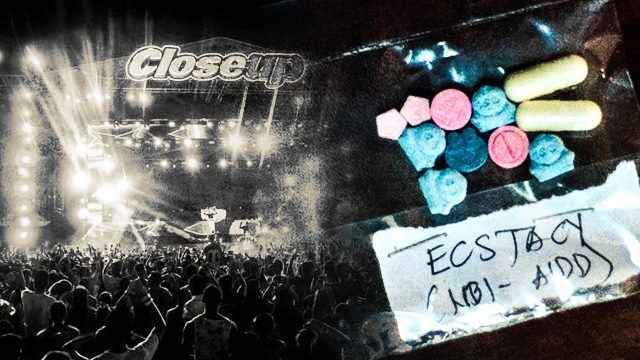

On the anniversary of the tragic Close Up Forever Summer open air concert where five people died after allegedly consuming an illegal substance, Rappler talks to drug dealers and people who use drugs (PWUD) about the risque mix of drugs and music.

1. Beware of fake drugs

Edge, who has mixed taking “Ecstasy” and going to a rave said, “I don’t know how to explain it but taking E just goes with the music. It heightens the experience of the thumping and the beat of the music. It’s like in your skin.”

Ecstasy (methylenedioxymethamphetamine or MDMA) has been a constant mainstay in the club, rave and music festival scene for a long time. It goes by other names like E, XTC, C, and love drug but its main effects are the same: it’s an upper that has an energizing hallucinogenic effect. Users are said to feel a euphoric “sense of social closeness and bonding” which many say is why the drug is so popular in the club scene.

In its earlier years, the drug was called speed. Today, its new street name is

“Molly” because of its supposed new molecular version of MDMA and has been popularized in songs by Miley Cyrus and Kanye West.

E comes in both capsule or pill form. The pills can be different colors and sometimes have cartoon-like images on them. The pure crystalline powder form of MDMA is usually sold in capsules.

“But if you buy the capsule, you can be sure that it is mixed with something else with like meth, cocaine or sometimes even Viagra,” explained Vivian.

These so-called “extenders” are used by suppliers as a way of marketing an old drug in a new way and to give the user a different, more potent kind of high and. One tablet of MDMA runs for about P1,000* ($20) and up while the capsule about P1,500 – P2,500 ($35 – $40). (READ: How Duterte’s drug war has affected rich users)

Capsules can be shared by 2 people and stretched to even 3.

2. Click to buy

Getting high is relatively simple. Pills or capsules are easy to get past security or sniffer dogs at a rave and to avoid that altogether, some pop the pills before going to the party.

Some dealers don’t even have to go to an event to reach their customers and users don’t have to wait for the next rave. They just meet online.

At a Congressional hearing following the tragedy at the Close-Up Forever Summer party, Philippine National Police Chief Senior Superintendent Manuel Lukban explained that “the deals of ecstasy is very different” from other drugs like shabu.

“Ecstasy proliferates through social media, through Facebook,” he said.

He might as well have included Pinterest. A quick Google search will show that there are Pinterest sites and websites of on-line sellers who can deliver ecstasy right to your doorstep.

In April 2014, the Bureau of Customs and Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency seized 500 tablets of ecstasy (with street value of about P750,000 or $15,089) from a big time drug supplier known to be the go-to drug guy for Metro Manila and other neighboring provinces. The suspected dealer in his statement said that traders and suppliers are using the Internet to bring in and sell drugs and using bitcoin as a mode of payment.

Vivian has seen a local Instagram page where you can buy drugs online, pay via LBC or Western Union and have the drugs shipped to you. (READ: Music, drugs, and alcohol: Do young Filipinos party to get high?)

3. The party scene set-up

Maia* started using drugs when she was 15. She started out with smoking cigarettes and weed and then went on to harder drugs like X and cocaine.

“My barkada were my neighbors. I got my supply from my friends and we would smoke up in each other’s houses,” recalled Maia who is now in her early 30s. The proximity and the familiarity provided Maia the perfect alibi. “Our parents never knew we were all getting high.”

Looking back now, Maia thinks that there was also a built in safety system in doing drugs within the confines of a friend’s house. “You’re in a small group with people you know. They can see if your body starts reacting to the drug and help you.”

Fast forward to today, people use drugs either in “in-house sessions” or small groups in someone’s condo or a rented hotel room or at raves.

“Let’s be realistic. If you’re at a party or a rave, one way or another, drugs will be available whether you like it or not,” said J, who as a DJ says she sees a lot from her booth.

J says it’s wrong to assume that everyone at raves is doing drugs but admits that she has seen people openly taking drugs and then downing them with alcohol – combined with the heat and body compression at parties can be lethal.

“Outdoor music festivals are sprouting up faster than mushrooms. Back then the rave scene was in a controlled air-conditioned environment. There were stations where people could sit down, rest and drink water,” J explained.

Nicole, 26, a regular raver, has complained about how hard it is to get water at an event. “There aren’t enough water stations in relation to the number of people who go, the lines are so long and water is P100 ($2) a bottle – more expensive than beer. It’s hot. You’re sweating like anything and if you are already high, you can get really really dehydrated.”

According to the US-based National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), MDMA can affect your body’s ability to regulate its temperature “particularly when it is used in active, hot settings like dance parties or concerts”.

Reactions can include hyperthermia which is a sharp rise in body temperature that can lead to liver, kidney or heart failure and in some instances even death.

4. Changes in the music scene

Migs, a DJ and party organizer says that a new trend in the music scene is the coming together of the world of raves and concerts. “A rave has a DJ playing and people primarily go for the music. At a concert, you go to hear and see someone perform. At a rave, drugs are expected, at a concert not so much.”

But now that DJs are bringing in singers and singers are performing with guest DJs, the scene has meshed together and is trying to capture a wider audience.

Some parties offer discounts for college students and some student organizations sell tickets to raise funds.

“I’ve seen really young looking kids at the raves and I see the drugs being pushed around. I worry about how they are taking in being exposed to drugs so young. Do they know what they’re getting themselves into? I know a lot of folks who don’t do drugs, it’s common but it’s not a must. Do these kids know how to say no?” said Migs.

Migs has seen many family members and close friends lose their way to drugs and knows the potential harm and damage goes beyond the user.

And though she comes from the other side of the drug scene, Vivian feels the same way. “It’s your choice to do drugs. And it is your responsibility to educate yourself on the risks involved.”

Maria Inez Feria, Founding Director of NoBox Philippines, says the perception of users in the Philippines is one that is highly stigmatized. The term “adik,” for example, carries with it a lot of connotations. Punitive policies on drug use don’t help.

“When we punish simple drug use, we drive people away from asking for help, wanting to help, and knowing how to help,” said Feria.

NoBox Philippines has been working with different advocacy and legislative groups to push for harm reduction policies as a response to drug use in the Philippines. Harm Reduction International defines “harm reduction” as “policies, programmes and practices that aim to reduce the harms” linked to drug use (like sharing needles, for example), rather than on the elimination of drug use itself.

Feria concluded: “We need to let people (know) that there are better ways to respond to people who use drugs, and it starts with being kinder and more honest about the drug use.” – Rappler.com

Ana P. Santos is Rappler’s sex and gender columnist. She is also Pulitzer Center grantee who writes about labor migration. In 2014, the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting awarded her the Persephone Miel Fellowship to do a series of reports on migrant mothers in Paris and Dubai.

*$1 = P49.71

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.