SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In March 2017, plainclothes policemen reportedly visited the house of Jan Joseph Goingo, then the College Editors Guild of the Philippines (CEGP) Vice President for Luzon, and interviewed him about his family.

This was contained in a report of the Ateneo de Naga University publication, The Pillars, where Goingo was a staffmember, to the CEGP.

In a separate incident, staffmembers of The Warden publication of the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila reported that they have had difficulty accessing the publication fund. According to them, the university’s finance office announced during the second semester in 2016 that their current semestral budget amounting to P500,000 will be carried over to the next academic year, 2016-2017.

These are just some of the campus press freedom violations recorded by the CEGP, the oldest and broadest alliance of college editors, since President Rodrigo Duterte began his term.

In all, CEGP said that there are over 800 unresolved cases of campus press freedom violations as of posting.

Importance of campus press

What is worse is that these reports remain underreported in the mainstream media.

“Kahit pa may mga hina-harass, may mga talagang sinu-surveillance na mga campus press, underreported pa rin siya dahil nakikita nila ang campus press bilang maliit lang or di kaya confined siya sa school lang,” CEGP President Jose Mari Callueng said in an interview with Rappler.

(Even though some student journalists are being harassed or under surveillance, the cases are still under reported because they [mainstream media] consider them as minor or confined within the school.)

University of the Philippines journalism professor Danilo Arao countered the idea that campus press issues are confined only within the university. He said that there should be “no distinction between national and local/school issues because they are interrelated.” (READ: Why campus journalists should go beyond classrooms)

“In discussing local/school issues, campus publications should relate them to what is happening community-wide or nationwide,” Arao said in a previous interview with Rappler.

Unlike mainstream media that also operate as businesses, Callueng noted that campus press have no commercial interest.

“’Yung campus press kasi, walang commercial interests dahil ang fund ay nanggagaling sa mga students themselves. Ano ba ‘yung nais ng mga estudyante? Siyempre ‘yung malaman ‘yung kalagayan ng lipunan,” Callueng said.

(Campus press don’t have commericials interestes because their funds come from the students themselves. What do students want? Of course, they want to know the truth about the state of the society.)

Campus press, according to Arao and Callueng, play an important role in educating the public and upholding democracy. This is both true historically and at present. (READ: Oldest alliance of college editors urges PH media to unite for press freedom)

In fact, Liliosa Hilao, the first political prisoner to die in detention during martial law under the Marcos regime, was a campus journalist from the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila (PLM). Like many progressive groups that dared to counter the narrative of the Marcos regime, CEGP was also declared “illegal” during the first years of Martial Law. (READ: #NeverAgain: Martial Law stories young people need to hear)

Many of the campus press then took the role of preserving freedom of speech and expression by going underground and joining the mosquito press.

“Sila talaga ‘yung nagsilbi na boses ng mga mamamayan at ito yung dahilan kung papaano sila namulat para ibagsak yung diktarduya ng rehimeng Marcos,” Callueng said.

(They served as the voice of the people and this is how they learned how to help in bringing down the Marcos dictatorship.)

Current violations

This critical role that the campus press is the reason why, according to Callueng, violations against their rights happen in an alarming scale, despite the existence of the Campus Journalism Act (CJA). (READ: Does the Campus Journalism Act protect press freedom?)

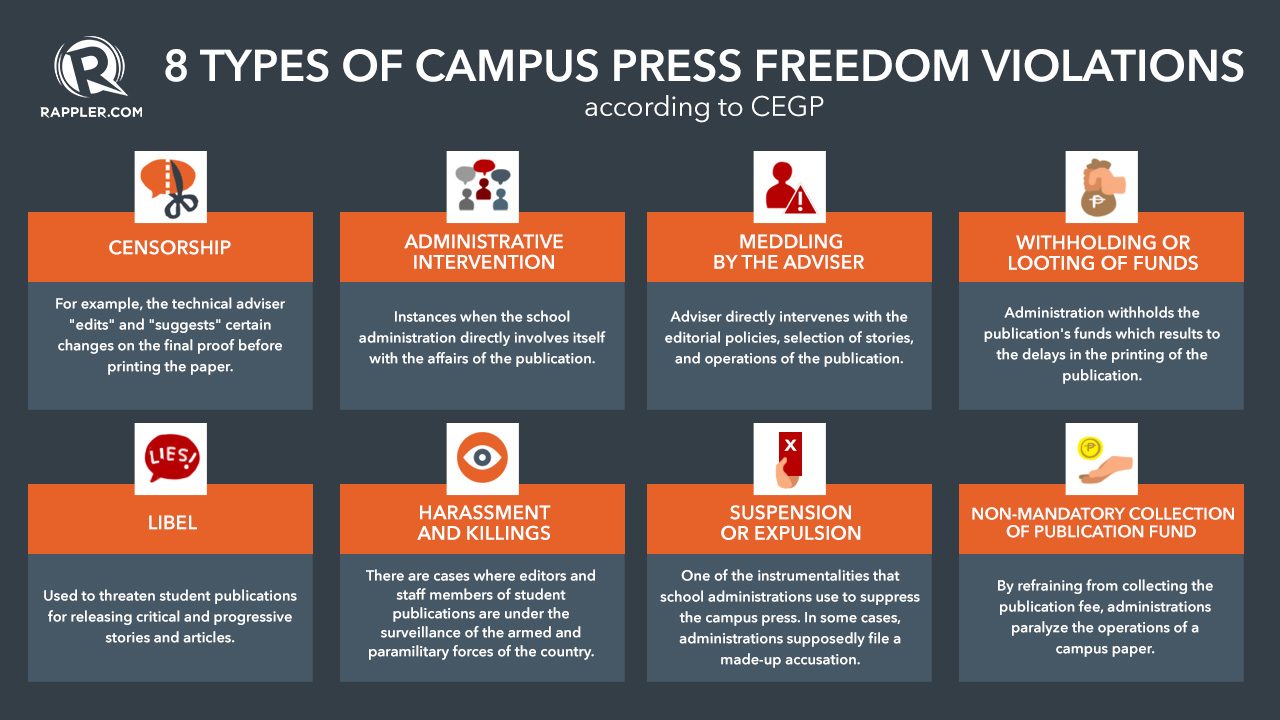

In CEGP’s 86 years, the guild came up with 8 categories campus press freedom violations, as shown in the following infographic.

Making sense of these violations, CEGP pointed to the “flaws and inadequacy of the law to genuinely protect campus freedom.”

According to the guild, while there are a couple of positive provisions introduced by the CJA, these can be “overruled by powerful decisions and actions of the administration.”

Fiscal autonomy

CEGP cited Section 5 of the law that stipulates where publications could get their funding. It states that “funding for the student publication may include the savings of the respective school’s appropriations, student subscriptions, donations, and other sources of funds.”

The guild argued that the word “may” in the provision may be interpreted by the administration as only an option to collect student publication fee. This, in effect, legalizes the non-mandatory collection of publication fee, the lifeblood of student-run publications.

Based on their records, at least 200 of the 800 cases of campus press freedom violations are related to the withholding of funds, making it the primary violation faced by student publications in the country.

“Which is why, ever since 2009, we’ve been pushing for the Campus Press Freedom Bill because this seeks to uphold the fiscal autonomy of campus publications,” Callueng said.

Introduced in the 16th Congres by former Kabataan representative Terry Ridon, House Bill (HB) 1493 included a provision on mandatory funding of student publications, among others that seek to address flaws in the CJA.

More than that, the bill also seeks to introduce a penal clause, according to Callueng.

Section 18 of the proposed bill states that any violation may be punishable by a “fine of not less than P100,000 but not more than P200,000 or imprisonment of not less than one year but not more than 5 years.” It also added that “if the offender is an education institution or a juridical person, the penalty shall be imposed upon the president, treasurer or secretary of any officer responsible for the violation.”

Addressing the violations

In the absence of a law that can genuinely protect the rights of the campus press, what can student journalists do?

“Ang challenge sa pag-address ng mga violations ay ‘yung paghaharap mismo sa conflicts of interests. Admittedly,’yung mga admin, siyempre hinding-hindi sila papanig sa mga ina-assert ng mga nasa loob ng diyaryo and that has been proven sa mga series of dialogues na napuntahan ko,” Callueng said.

(The challenge in addressing these violations is facing the conflicts of interests between the school administration and the student journalists. Of course, the school administration will never side with the views of the school paper, and has been proven in the series of dialogues I have been to.)

A united campus publication and student community are important in addressing campus press freedom violations. According to Callueng, this can be achieved through effective and consistent information awareness. CEGP has also advised student publications to file cases before the Commission on Higher Education (CHED).

To help uphold their the rights of campus media, CEGP has been at the forefront of raising awareness on the mandate of the campus press. (READ: Oldest alliance of college editors to stage nationwide protests February 23)

“Especially during these interesting times, we need to inculcate among members of the campus press their solemn duty – that they are not just a paper for the students but also a paper for the rest of the public,” Callueng said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.