SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

“Mahirap pumasok sa UP, pero mas mahirap lumabas,” a saying at the University of the Philippines (UP) goes.

“Mahirap pumasok sa UP, pero mas mahirap lumabas,” a saying at the University of the Philippines (UP) goes.

(Entering UP is a challenge, but graduating on time is more difficult.)

Surviving both the academic rigor and life challenges at UP is a shared story of many state scholars or the “iskolar ng bayan.”

An “iskolar ng bayan” can fail to graduate on time because of an incomplete grade in a Math subject; or, as in my case, because of financial constraints.

Costly education

Studying in UP is costly, especially for my family with modest means. This came as a surprise since I was supposedly studying in a highly subsidized state university.

Although I was able to graduate relatively on time (I finished college after 5 years since I transferred from UP Baguio to UP Diliman), financial constraints constantly made obtaining my diploma challenging.

Long queues before you reach the loan board, stacks of required documents, frequent trips to Vinzons Hall where students’ affairs are facilitated, rackets and odd jobs, scholarship applications, and innumerable appeals summarize the story of how I was able to survive in UP.

My story about how I struggled during my college years can be told in 3 parts.

It starts with my yearly application for the Socialized Tuition and Financial Assistance Program (STFAP) of UP. Next is the arduous process of enrollment and applying for short-term loans; and then the ups and downs of the daily grind throughout the semester.

‘I am poor, please believe me’

The tedious process of applying for the STFAP is a common complaint among UP students.

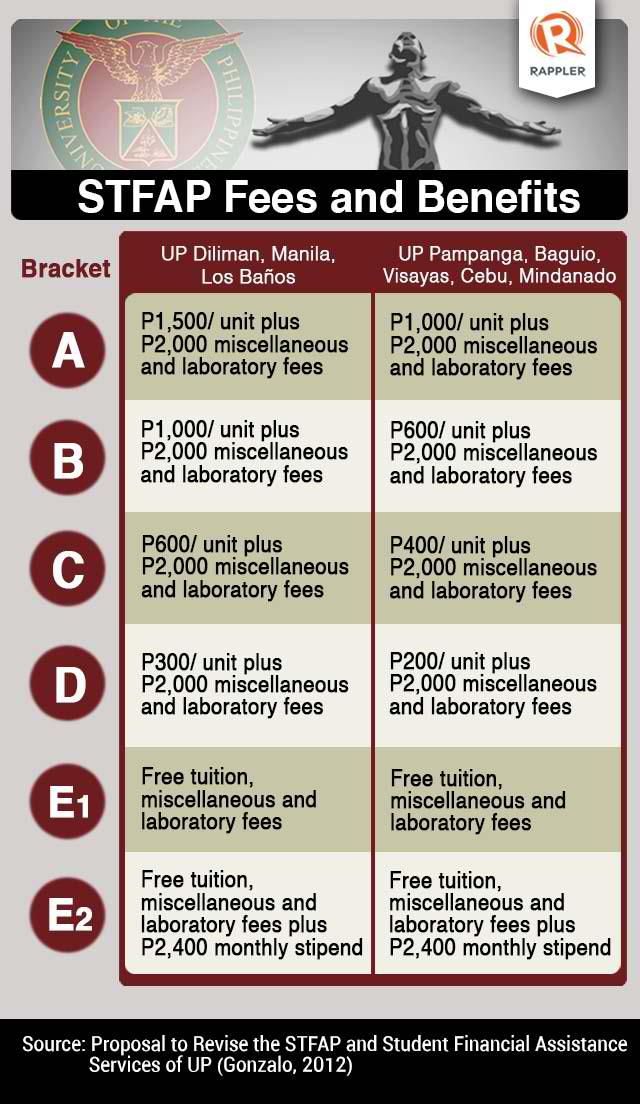

STFAP is the bracketing system of UP that determines how much tuition a student should pay based on his or her socio-economic background. The richest students are assigned to bracket A and must pay P1,500 per unit; while the poorest students are classified under bracket E1 or bracket E2 and pay next to nothing.

The process involves accomplishing a 14-page application form plus securing several government documents, including an income tax return (ITR), a certificate of non-employment, a birth certificate, etc.

The long process taught me to be patient, resourceful, and persevering. I also learned these traits from my mother.

Before I could even ask for her help, she would have aready made a trip to the municipal hall to get necessary documents. All I did was to fall in line to file my application.

“Kung hindi rin magtitiyaga, walang mangyayari. Hindi ka talaga makakapag-enroll,” she would usually remind me. (If we don’t persevere, nothing will happen and you will not be able to enroll.)

Series of appeals

Despite an annual family income of P80,000, I was categorized as bracket B on my initial application. In the bracketing system, a student whose family income falls below P80,000 is supposed to be put in the lowest bracket E.

As a bracket B student, I paid the tuition fee of P1,000 per unit. Over the next two years, I applied for reconsideration and was reclassified under bracket C. Things went well as my tuition fee got reduced to P600 per unit. In my fourth year in college, I was moved to bracket D paying a lower P300 per unit.

In my last year, I finally got the bracket that I deserved. I was placed in bracket E1 and, for the first time, I skipped the queue for loan application.

A student who falls under bracket B with an academic load of 18 units pays around P20,000 a semester. This amount includes the miscellaneous, laboratory, and other required fees.

Paying the full amount of tuition on enrollment was just not feasible for me. Even when I was in bracket D, I had to apply for a loan to lessen the burden on my family.

Debt row

My regular routine during enrollment in UP consisted of lining up at Vinzons Hall to clear my outstanding loan from the previous semester, trooping down to my college to enlist for classes, returning back to Vinzons Hall to apply for another loan, and then proceeding to the cashier to pay other outstanding fees.

It may sound simple, but the process would usually take several days to finish.

Lines in the loan board would normally snake through two floors of the building—an indicator that many UP students cannot afford the full cost of a UP degree.

Humor being the escape of most Filipinos, the students have called the hallway “debt row.”

In the “debt row,” students and parents patiently line up, hoping to get approval for a tuition fee loan. With the tuition fee loan offered by UP, students can obtain a loan of as much as 80% of their tuition. In return, the students are required to pay for the loan by installment throughout the semester.

I was able to talk to a mother of an engineering student. Over bread and juice that she shared with me, we laughed at how the “debt row” even beat the queue for lotto tickets.

She lamented that UP has become costly for a state university.

“Kaya ko pina-enroll dito anak ko kasi akala ko mura, UP, eh. Hindi ko alam na kailangan ko pa rin pala pumila,” she said. (I enrolled my son here because I thought UP is affordable. I didn’t know I had to line up as well.)

The daily grind

The story does not end with enrollment. More difficult than the enrollment process is trying to stretch my allowance on a daily basis.

With the thick stack of required readings, costly production requirements, dormitory fees and lengthy research papers, my meager allowance of P500-P1,000 per week could not cover all my needs. In a span of a week, the amount could only cover my food expenses.

I had to find a way to survive.

Since my first year in college, I managed to juggle an array of jobs that earned me just enough. I worked in a fastfood chain, served as a student assistant, tutored Korean students, transcribed interviews, and did writing jobs.

To some extent, these jobs worked to my advantage. I benefited in other ways beyond earning a salary. As a student assistant in the library, I was able to hoard books for my research papers. Serving in a fastfood chain also meant free dinners.

Beating deadlines, finishing projects, and passing exams with flying colors were challenging enough on their own. Working part-time jobs on the side added more spice to the mix.

There were several instances when I went to my classes deprived of sleep after spending the night editing a video production for school or writing an article for work at Rappler. Things came to a head when I had to choose between attending my class or finishing my work.

Rising to the challenge

The activists’ battlecry – “Education is a right!” – has become my own reality. Through this experience, I have come to believe that education has been reduced to a privilege for the lucky few. Its accessibility to poor but deserving students has become questionable.

Ironically, while society emphasizes the importance of education as a ticket out of poverty, it still remains beyond reach for most Filipinos.

Education as a right has been reduced to a mere slogan – not on placards but in the government’s expenditure on education. While the education sector receives the highest allocation in the budget, this represents only 2.5% of the Gross National Product (GNP). The United Nations recommends a ratio of at least 6% of the country’s GNP.

The existing education allocation pushes state universities like UP to devise programs and policies that aim to raise additional revenues.

These include the implementation of the STFAP bracketing system. Meanwhile, private-partnership programs like the UP-Ayala Technohub along Commonwealth Avenue and the ongoing construction of the UP Town Center along Katipunan Road serve to bring in revenue from UP’s idle assets.

These self-sustaining projects depart from the UP charter which holds the government responsible for providing adequate funds for the state university.

My 5 years in UP seemed like a perpetual cycle of survival; but I finally made it. However, the students next in line are still trapped in the same financial merry-go-round. Hopefully, breaking free from this cycle won’t be just a dream for them. – Rappler.com

Raisa Marielle Serafica recently received her BA Broadcast Communication degree from the University of the Philippines – Diliman. She now works as a researcher/writer for Rappler.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.