SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

BAGUIO CITY, Philippines – In this age adventure tourism, more and more people are coming out of the concrete jungles of the city in search of the great outdoors. These days it seems it covers the entire range: the yuppies, members of high society, and even the students in our colleges, seem to be taking up the pack and hitting the trail.

All well and good, as this practice has brought about a greater awareness of the plight of our environment, as well as a great clamor to save what is left of our precious ecosystems. But what any environmentally conscious outdoor person seems to forget, in the clamor to pack out all waste and leave no trace, is that these places also have people and cultures who have lived in these areas for centuries undisturbed by time and living as one with the land.

Anyone who has gone through elementary education in the Philippines has probably been taught that kaingin, which most mountain farmers employ, is bad for the environment. Rightly so, but let us look at this in another light. The people living in the mountains have been practicing this method of farming for centuries, yet it is only in the last hundred years that our forests have gone from a hefty 80% at the beginning of the 1900’s to a meager 17% at present. (Latest available figures from the Forest Management Bureau now indicate a minimum 24% forest cover.)

Let us ask ourselves, why do we portray this practice with such fervent propaganda? It is ingrained in every Filipino child’s mind that kaingin has been the cause of the loss of our nation’s forests, when it was only in the last century — with the coming of modern logging technology — that our mountains have been laid bare and robbed of all their glory.

Adventure tourism has brought about a greater awareness of the environment in which we live in, yet these adventurers seem to forget in their haste to reach the summit and conquer the mountain that, mountaineering is not only about who is the fastest or who takes down the most trash, it is also about the people, not the adventurers, but the true mountaineers — they are the children of the mountains.

City lives

Mountain after mountain, throngs of mountaineers, excursionists, and tourists go searching for the thrill and adventure of the outdoors, taking care to leave no trace and save what is left of our precious environment, yet it seems that they miss quite a few important things as they go up the mountain. I have seen more and more flock to these mountain hideaways, with hired porters and guides, with their cars and their music. They bring with them their city lives.

Again and again we see it, the lives of children of the mountains, their culture, irreparably changed by the onslaught of tourism. Although tourism does bring a source of livelihood for them, it also brings with it something else.

Watching this happen can be likened to the biblical Adam and Eve. These people of the mountains live in Eden, happy and unaware, living their lives in the blissful freedom of their mountain homes. We, the tourists are the snakes, who bring the forbidden fruit of civilization, to the people who call freedom their home.

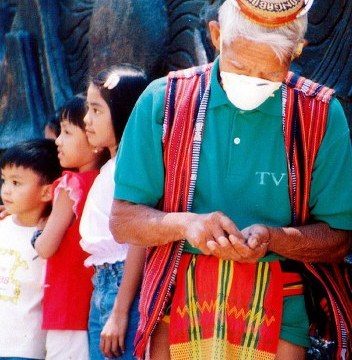

In Ifugao the people have been so changed by tourism that they only don their traditional clothes if tourists will pay them to take their pictures. I have often asked why it has come to this — do they not take pride in what is theirs? Has tourism opened their eyes to the shame of wearing their traditional garments?

In Battad you will see signs at every inn, and Battad has quite a few, which say, “WE SERVE COLD SOFTDRINKS AND HOT PIZZA.” On one visit there I asked myself, was I a part of this change? Where was the tapuy and itag? They had been replaced by the tourists’ clamor for pizza and ice cold Coca-cola.

Once somewhere in the Cordillera mountains, a local, who I had the pleasure of becoming friends with, asked me, “Nu mabalin ko nga saludsudin nu apay nga mapmapan kayo idtoy? Inya ti maala yu idtoy ngay?” For the first time I had no answer to the question that had been asked me numerous times by my friends and family. I did not know what to say.

For the mountain people, my adventure was their daily life, and for me their life was a great adventure.

If we are to stick to our promise to leave no trace and leave the mountains as free as when we first came, let us not bring our “ideal” city lives to them. Instead let us bring back to the city the freedom and simplicity of the people from the mountains of Eden. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.