SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Refugees who left their homes to save their lives. Children who witnessed deaths that are numbered way more than their years. Mothers who struggled to save their children from calamity, hunger, and conflict.

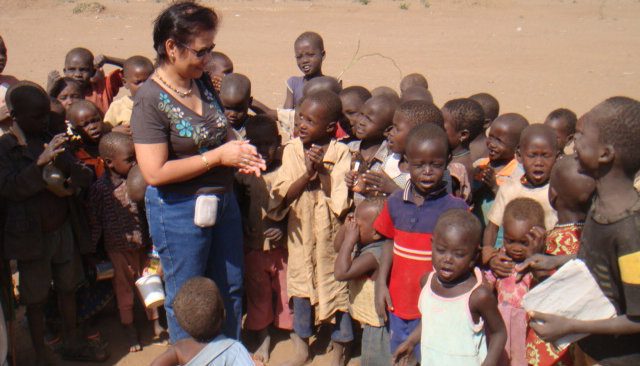

These are the people Lourdes Ibarra usually meets all in a day’s work.

In times of calamity, extreme poverty, and civil conflict, humanitarian workers from around the world rise to the challenge of helping people fight hunger and insecurity. They go to places devoid of stability, security, and food assistance at the expense of their own comfort and safety.

As a humanitarian worker for 17 years, Ibarra experienced living at the remotest area in Africa and Middle East to respond to the needs of people affected by famine or natural disasters. Currently, she serves as the head of the programs of the World Food Programme’s (WFP) operations in Damascus, Syria, assisting more than 4.5 million victims of the civil conflicts.

According to a study presented by the United Nationas Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA),144 million people are either devastated by disasters or displaced by conflict in 2012. On the other hand, international organizations targeted 65 million people for humanitarian aid through inter-agency appeals.

In the Philippines alone, in 2013, humanitarian workers from all over the world flocked to Eastern Visayas when Super Typhoon Yolanda hit the country to complement the government’s response and recovery efforts.

Road less taken

While Ibarra didn’t choose the profession out of convenience nor for its perks, she definitely was not prepared for the demands it required. In providing aid to those in need, Ibarra faced threats posed by nearby insurgents and even experienced settling in places with undesirable living conditions.

“Being in the deep field, a woman [like me] faces challenges in the lack of decent accommodation and basic facilities. I have experienced to be in deep, deep field when we used to live in tents with common toilets and shower in Bor, South Sudan, with the presence of snakes and teeming with mosquitoes,” Ibarra shared.

But the challenges are not isolated to security issues. From her 17-year experience, Ibarra also experienced problems involving politics, cultural acceptance, and gender inequality.

“Real time challenge that women sometimes face is when they are misunderstood and at times subject to harassment. Cultural acceptability and adaptation can sometimes pose challenges particularly in a closed society,” Ibarra added.

However, instead of dampening her resolve, Ibarra said that these challenges ironically encouraged her to continue her service. Seeing the smiles of the children, women, and elderly who received the most needed assistance became her driving force.

Heartbreaks

For her, the problems she faced as a humanitarian worker pale in comparison to the plight and stories of the people they help.

As head of one of the offices in Somalia, Ibarra managed the feeding program for more than half a million refugees during the height of the crisis at the Horn of Africa and the unprecedented influx of refugees from Somalia. With tens of thousands Somalis arriving at their camp per week, Ibarra said the situation was almost unmanageable.

Ibarra recalls the story of a Somali family – a mother and her 3 children she met during her service at the Dadaab Refugee camp in Somalia.

They arrived at the camp hungry and tired. They persevered walking for 20 days under the scorching heat of the sun and with limited water and food supply.

They were 7 when they started their trek. Two of her children died along the way due to hunger and infection. Her husband, on the other hand, was taken by the Al Shabaan, a militant group. The Somali mother had no choice but to bury her two children and leave them behind.

“I was upset for a few days; the scenario of what the family went through came flashing back,” Ibarra said that it was this kind of stories that both drained and strengthened her.

“It is when you give yourself for this noble cause that you truly give”

– Lourdes Ibarra

Ibarra had the family closely monitored. She also directed their enrollment to the supplementary feeding programs until the family fully recovered.

“Then my following visit to the camp was so rewarding – I saw the mother and the kids smiling to their ears and rejoicing as they restored their health. I cried of joy, of fulfillment!” Ibarra recalled.

Continuing the cause

Humanitarian work, for Ibarra, is a tug-of-war between the impossible challenges and fulfilling rewards that come with the profession. Regardless of these, she cannot imagine herself doing something else other than providing assistance to the needy.

“I am here because I understand what poverty means and what it is like not to have all those luxuries and comforts in life,” Ibarra added.

Nothwithstanding the herculean demands of her job, Ibarra believes that it does not really take so much to become a humanitarian worker.

“If I am asked to define ‘humanitarian’ work in one word, for me it means ‘giving’. Because it is when you give yourself for this noble cause that you truly give,” Ibarra said. – Rappler.com/with a report from Jodesz Gavilan

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.