SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

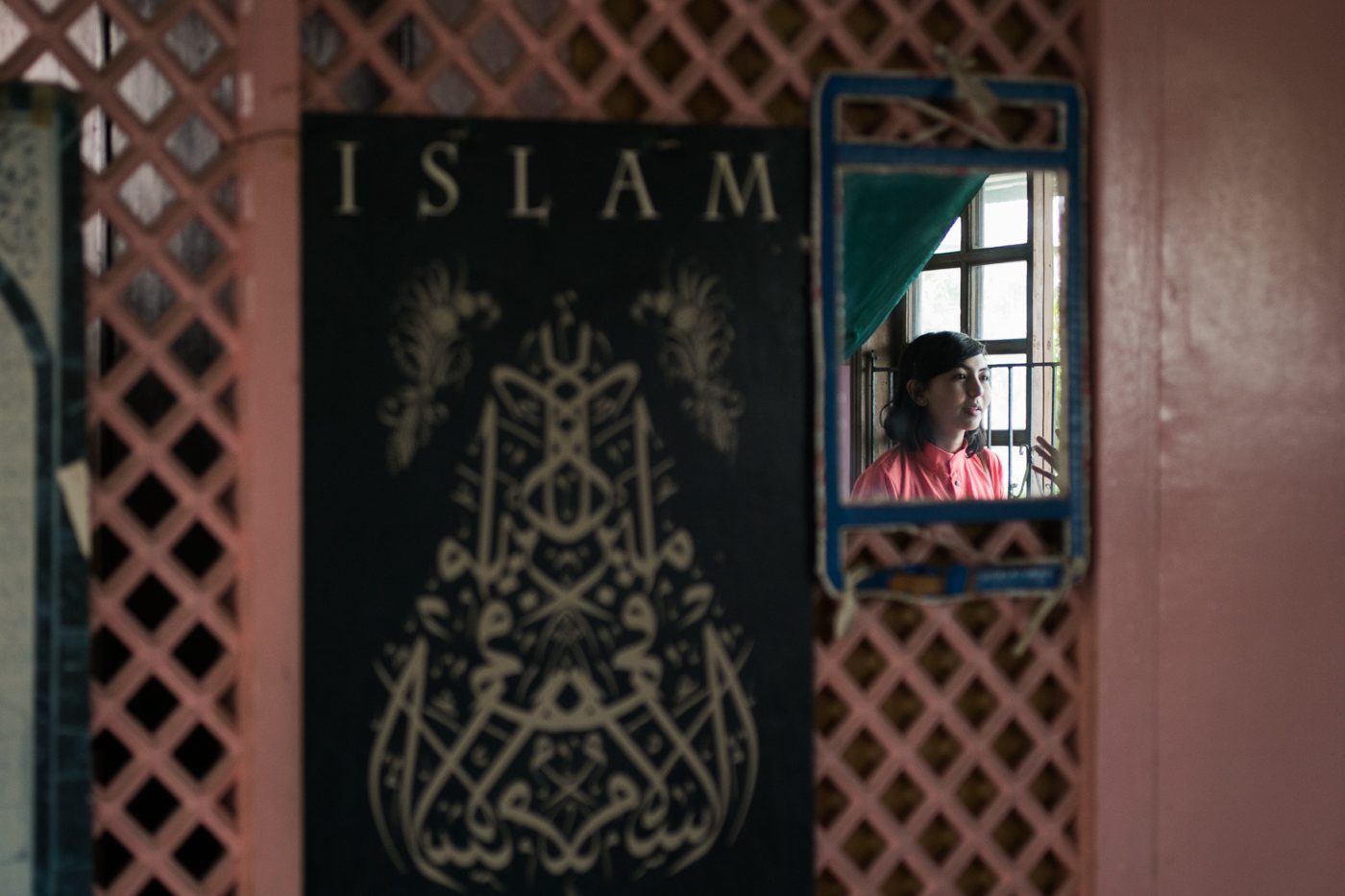

MANILA, Philippines – A group of girls in colorful hijabs and long skirts are laughing in the middle of a parking lot. One of them is wearing sunglasses. Another arrives donning a leather jacket over her long sleeves. They call one another sisters, even us, although we are not of the same faith.

One of the women, Jannah Valdez, asks Rappler: “Takot ba kayo sa amin? Akala niyo ba terrorista kami?” (“Are you afraid of us? Do you think we are terrorists?”) She laughs, telling us that she and her husband used to feel threatened by Muslims before converting to Islam.

Her question reflects what Abraham Sakili, PhD, a professor at the College of Arts and Letters of the University of the Philippines Diliman, calls the “negative Moro image,” which persists in the minds of non-Muslim Filipinos today. The discriminative effects of the “negative Moro image” range from seemingly trivial instances like taxi drivers refusing to go to areas like Culiat and Maharlika, areas known to be populated by Muslims, to impactful consequences like hindering peace and equality.

According to Jamel Cayamodin, PhD, an associate professor III at UP Diliman’s Institute of Islamic Studies, Muslims are automatically labeled as extremists, uneducated, and poor due to what appears in various forms of media. He explains that with the immediate and far-reaching power that it possesses, media greatly influences not only audience’s perceptions but also their behavior. Viewers instantly believe what they see on television, movies, or the Internet without even confirming the veracity of those portrayals.

Minah Basman, a clinical psychology student finishing her PhD, explains that aside from the media, the educational system also plays a part in the perpetuation of these stereotypes. History classes often highlight jihad or the holy wars that the Muslims fought in the past, instead of the fact that large parts of the Philippines was Islamic and were independent and sovereign, before the country was colonized by the Spaniards.

Basman adds that stereotypes breed negative expectations that, when broken, surprise non-Muslims. She recalls receiving several offensive comments:

“Muslim ka, bakit nag-eexcel ka at bakit malinis ka?” (“You are a Muslim. Why do you excel and why are you clean?”)

“She is Muslim but she is peace loving”

“Muslim ka, okay lang, pero maganda ka pa rin,” (“You are a Muslim, but it’s okay, because you’re still beautiful.”)

Yes, they are Muslims – and they are doctors, professors, artists, fathers, mothers, and everyday Filipinos. And these are some of their stories.

Jannah and Yusuf Valdez

Jannah, a pediatrician, and Yusuf, an architect, met during a soireé. They were both studying in a Catholic school; she was a Catholic and he was an Iglesia ni Cristo.

Whenever Yusuf saw a Muslim on the street, he would tell his wife, “Look! Masamang tao (bad people).” According to Yusuf, this misconception was largely due to what he saw on television and in movies. In an attempt to find words he could use against them in the very book they deemed holy, he started reading the Qur’an. Expecting to find garbage, he found gold and eventually converted to Islam, which he practiced secretly at first.

One night, he finally told his wife, “I’m a Muslim.” In disbelief, she started bombarding him with questions. “Just read the Qu’ran,” he said.

She did. She also became a Muslim.

Aside from being busy with work, their two kids, and medical missions, Jannah and Yusuf are now active volunteers of New Muslim Care, a non-profit organization that also serves as a support group for new converts or Balik Islams. One of their activities was the Ramadan Mubarak Food Caravan, which was a 3-week feeding program conducted around Quezon City and Manila. They drove around specific areas and distributed food to the homeless on the streets.

During the last week of the caravan, one of their Muslim friends got out of the car and handed two bottles of water and some food to a thin, disheveled boy. He walked back to the car. The boy immediately dropped his bags, sat on the side of the road, and ate. Seeing this, he turned back and sat beside the boy for a while, struck a conversation, and accompanied him while he ate what was probably his first meal in days.

Fatima Abdalla

Fatima, a writer, used to be a devout Catholic who regularly participated in church activities. After living with a Muslim family in Dubai, she realized that she wanted to go back to her country and contribute to the practice of true Islam which, according to her, was about “worshipping one God, unity of people, respect for all mankind and creation, and compassion and peace.”

Although her faith in Islam is strong, she says that people who practice different religions are still their brothers and sisters.

Abdalla founded Ramadan Tent, a yearly event at the Quezon Memorial Circle that is organized for Iftar, or the breaking of the fast every night during Ramadan. The tent itself serves as the prayer room while the surrounding area was set up for cooking and eating.

Although Ramadan is an Islamic tradition, the Ramadan Tent welcomes non-Muslims as well. Abdalla says that it is a venue for their brothers and sisters from other religions to witness how Islam is practiced. Aside from the cultural awareness that it brings, the Ramadan Tent also serves as a common ground where Muslims and non-Muslims alike can eat and converse.

Tani Basman

Tani Basman carries himself with a gentleness that only a father could have. He and his wife have a 6-month old son and another one on the way. He spends his free time taking care of their baby and playing basketball.

Other than being a father, Basman is also the investor relations officer of 8990 Holdings, a company that provides low-cost housing in different areas.

Being in the corporate world, his advocacy is to provide business opportunities in Mindanao. According to Basman, there are many lawyers and doctors there, but what people in Mindanao need is economic progress and business opportunities.

“There’s this notion in Mindanao that if you want to make it big, you have to go to Manila,” explains Basman. He hopes to gain enough experience and capital in order to start a business in Mindanao, wherein people are hired based on competence, not on religion.

He wants to provide opportunities for employment so people will not have to leave home, and a working environment where people will not hesitate to apply due to fear of discrimination in the workplace.

Farah Ghodsinia

Unlike most Muslims, Farah Ghodsinia does not wear a hijab but she speaks highly of her religion. According to her, the hijabis a symbol of modesty, but modesty can be manifested not only through one’s dress code but also through one’s character. Being the best person that she can be and trying to change the world for the better is Ghodsinia’s way of manifesting her love for her god.

Ghodsinia was born Muslim but spent majority of her life studying in an exclusive Catholic school before transferring to the University of the Philippines where she finished her undergraduate studies. She is currently the president of the 10th Youth Parliament, a manager of the Children of Mindanao (an organization that distributes educational kits to students in the ARMM), and a law student.

She recalls already wanting to make an difference even when she was a child. However, law is not her end goal. Being an advocate of human rights, she hopes to delve into government work to create a larger impact.

“‘Yung dream ko ay ‘yung dream nila ay matupad (My dream is to make their dreams come true).” She wishes to be able to provide basic needs for her fellow Filipinos so that they may have the capacity to become whoever they want to be.

Flordelyn Umagat

Flordelyn Umagat is the principal of Maharlika Elementary School, a public school that is mostly composed of Muslim students. This is where children of different faiths peacefully co-exist daily.

Being a Christian who used to know little about Muslims, she recalls being afraid of niqabis, Muslims who wear veils that cover their whole face except their eyes.

“Ang Muslim, matapang. ‘Pag nagkamali ka ng salita, papanain ka nila (Muslims are aggressive. If you say something wrong, they will strike you with an arrow),” was the common misconception she believed in. This fear was due to her ignorance of their culture and religious practices.

When she became conscious of the reason behind certain customs, she realized the importance of awareness in the pursuit of peace.

Ever since she became the principal, she became focused on promoting peace through education. The teachers in Maharlika Elementary School, which is also composed of both Muslim and non-Muslim teachers, are consistently being educated about the different faiths and cultures while being trained to treat every student equally.

“Yung thinking lang na dapat mawala is ‘Muslim ka, non-Muslim ako, magkaaway tayo’ (The thinking that must be eradicated is the notion of Muslims versus non-Muslims),” she asserts. This idea is passed down to students because Umagat believes that educational institutions should be the first advocates of peace. If children learn to propagate peace in school, the pursuit of equality will continue even outside the educational institution.

Although these are just a few stories, Ghodsinia, along with other Muslims assure that there are many more like them who are committed to eradicating prejudices and living the true Islam, which is “a religion of peace,” not of war or terrorism.

Tani Basman, Minah Basman, Abdalla, and Ghodsinia feel a strong sense of responsibility to set a good example as a way of breaking the stereotypes attached to Muslims. Basman believes that interactions with more Muslims will help people realize that they are not much different.

Attaining equality is not only a one-way process. Abdalla acknowledges that in order to break the stereotypes, Muslims have a responsibility to live according to the teachings of their religion while non-Muslims should be willing to listen to their stories.

In the end, the decision to accept or to shun Muslims still lies with them, but Abdalla hopes that non-Muslims will at least give them the opportunity to show the world that they are more than what they are branded to be. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.