SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

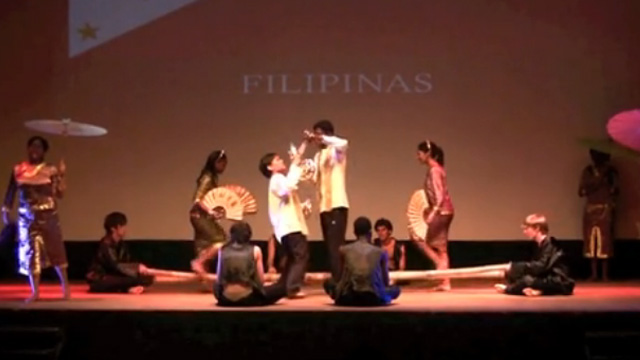

The applause dies down. The last dance number retires backstage. Gold jewelry and costumes are readied, while onstage, 6 boys stand in shadow, holding bamboo poles.

The applause dies down. The last dance number retires backstage. Gold jewelry and costumes are readied, while onstage, 6 boys stand in shadow, holding bamboo poles.

Suddenly a flute squeals, drums beat, lights brighten, and the boys start pushing and pulling on the bamboos, evoking great ocean waves. Two girls, their faces hidden by golden fans, come forward, reveal themselves, and high-step across the stage.

That’s my cue: I jump in, wielding a plastic sword and shield, facing a tall black man similarly armed (who is actually one of my best friends), and we take the battle to the waiting bamboo grill.

That’s how our singkil began.

It grew out of a simple idea—but one whose time had come, to quote Victor Hugo. I was quite nervous on the night of the show, but I am grateful to this day that it all worked out.

True, I had considerable luck that night; but just as important were the lessons I’d learned from working with my equally talented co-dancers.

Preparations

In 2011, as a 2nd year international student in Costa Rica, I had a lot to worry about. Besides finals, college applications, and graduation, we were to also stage the Anniversary Show. It showcases dances from various countries, all over the world—and it obviously requires intensive preparation.

I had quite a dilemma on my hands: should I join the Show, or free myself of the hard work I knew was awaiting my friends?

Stately in execution and remarkable in its intricacy, the singkil is a difficult art to master. It looks beautifully regal to any audience—the crossed bamboos, the elaborate costumes, the staged wars over power and dignity—but it says nothing of the behind the scenes effort and stress that tax the performers.

Enduring this taught me 3 things. That one must willingly trade comfort for the expected risks; properly balance grand ideals with practicality; and respect his or her cultural heritage to pull off a truly passionate performance.

Learning the singkil would’ve been easy enough were I merely another dancer—which I was, in the previous year’s performance, organized by Angel, a friend of mine.

But as the only Filipino left on campus after Angel graduated in 2010, and with no other offers to lead, I seemed the natural choice to take her place. Plus, I don’t consider myself a good leader, and yet here I was, supervising 13 other dancers.

The problems didn’t stop there.

Adjustments

I struggled to recruit enough dancers in time—and several recruits later dropped out, some mere days before the show. I had much less time to train their replacements, and I’m sure this visibly affected the actual performance.

But these were necessary risks, and thanks to them, I now know that choreography is not an insurmountable skill. I surprised even myself in that regard.

Today, such risks no longer seem so overwhelming.

Practicality is another issue. Though seldom prioritized, it can’t be overlooked: practice schedules conflict, costumes need fixing, dancers forget their moves.

I had to cut corners to make the dance work. In lieu of devising my own choreography from scratch, I had to adapt parts of Angel’s rendition. I dispensed with extra props; I taught my partners how to hold the bamboos properly, instead of having handles installed.

I even had to cut short the background music, simply to lessen the dance sequences—and I very nearly missed giving the sound staff the edited track. Balancing between perfection and realism is tricky to say the least.

Watch Singkil performed by the Bayanihan Dance Company:

Iconic dance

Luckily, the performance passed audience scrutiny fairly well. Whenever I admit to the slight mistakes visible on camera in the final dance, my friends reason that the audience wouldn’t have noticed anyway—and for the most part, they were right.

Yet I would rather make trivial mistakes in the final dance, than miss the opportunity to make that dance a reality. It was hard work, but I loved doing it.

When I asked family and friends for advice, they said no one would hold it against me if I didn’t join, or if I performed a simpler dance. But somehow, it’s not the same—to an international audience, the bamboo dance is one of the most iconic of dances, carrying a prestige paralleled by few. I also felt that I’d been saying no for too long—so I finally agreed.

I think that sense of pride sustained me when the practices were almost falling apart. Still, it wouldn’t be possible without my supportive fellow dancers and friends, and that sense of intercultural teamwork, crucial to our success.

The singkil, though only one of our many colorful traditions, embodies the cultural finesse valued both by ancient Filipinos and their descendants today. Its place in Philippine cultural heritage cannot be overstated. Perhaps because of that, I could endure sleepless nights overseeing the practices.

Pride

Naturally I became very stress-prone during that time. I threatened to cancel the dance if I didn’t get enough recruits. I snapped when people came late to rehearsals, and I nearly had a nervous breakdown on stage, in the final hours before the performance.

People were telling me to calm down and do my best, but I willingly put up with all this because of the burden of cultural representation I’d voluntarily taken on.

I could have walked away from the Anniversary Show—in truth, no one was asking me to dance. But in representing my home country, in the company of schoolmates of some 70 different nationalities, it all seemed worthwhile.

The final performance was far from perfect; I could hear the bamboos clap out of time with the music, and see the boys take missteps, all this before a huge crowd. Looking back at the video of the show, I notice even my own small errors. And yet, people believed in us, and the dancers themselves were content.

I have not enough space to name them all here, but I still thank them today for their invaluable help. They taught me to face up to tough demands, to balance perfection and pragmatism, and to stand proud for the culture defining a nation and a people.

Perhaps these lessons are best summed up in one word: commitment. I had to commit to the dance and all its attendant challenges. I had to commit to the one thing it all started with: the idea.

Anything less than commitment and the audience might notice—which is all very well, then, that they didn’t. The dance wasn’t perfect—but did it have to be? I learned a lot in the process, and I am still proud today that I did not dismiss that opportunity. That, in itself, is better than a perfect singkil.—Rappler.com

Jan Michael Ramirez graduated from the United World College of Costa Rica in 2011. He is currently majoring in English Literature at Westminster College, Missouri, in the US, and plans to graduate in 2015.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.