SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

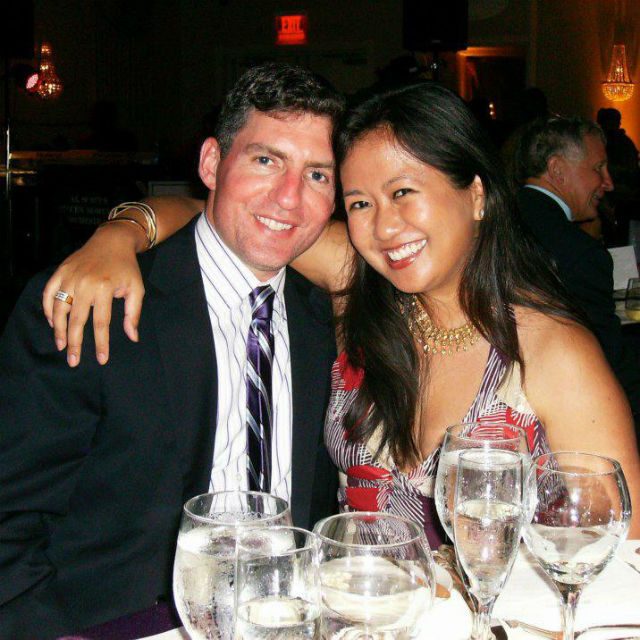

I joke with my husband J. that we look like a United Colors of Benetton ad: me, a Filipino raised Catholic in Saudi Arabia and him, a white American Jew from right outside Boston.

Because I grew up in Saudi Arabia, the little I knew about Judaism came from Fiddler on the Roof (my sisters and I sang “Matchmaker, Matchmaker” with our mother’s half-slips on our heads), The Diary of Anne Frank, and The Ten Commandments.

Books about Jews were pulled off library shelves, and sections in our American textbooks about the Holocaust or Israel were covered with opaque white labels. Until a few years ago, I did not know that there was a shul in Manila or that President Manuel Quezon had saved 1,200 Jews by allowing them to live and work in the Philippines from 1937 to 1941.

Through my 20s and early 30s, I assumed I would end up with someone white and Christian or agnostic. My closest friends are from my Episcopalian high school, and I imagined I’d meet the Future Him at a reunion or a friend’s Christmas party.

But, interracial dating presented its own unique challenges which I had eventually grown tired of. I didn’t want to meet another set of parents who told me that “Filipinos are a happy, hard-working people.”

Being told that they “didn’t think of me as Asian” and “you’re not very Asian” was beginning to make my skin crawl. Other men didn’t think that race was a concern at all and that was an issue for me. Though I was equipped to shrug off general, anonymous racism and daily microaggressions in public, I no longer wanted it in my home. I thought that I could find that peace by dating an Asian. (READ: What I’ve learned from dating a Filipino woman)

When J. wrote me in December 2010 (we met online) and I saw that he was “conservative, Jewish,” I was sure I was going to be just a phase. I’d heard stories from friends and students similar to Sex and the City’s Charlotte York who converts before she marries Harry Goldenblatt.

I wasn’t going to convert, so prior to even meeting him in person, I figured that whatever relationship we had would be finite. I didn’t even dress up for our first date. I wore a flannel shirt, corduroys, and a black puffer coat that looked like a sleeping bag.

But, not even 3 weeks later, I whispered to my friend A., “I’m going to marry him.” This certainty was the reason I invited him to the Philippines where he ate 18-day balut ( boiled fertilized duck eggs) with my best friend’s husband.

The only boyfriend I brought home with me, J. had pigeon’s blood dropped into his eyes when he took him to a manghihilot (faith healer) where a 20-foot Black Nazarene statue lay against a far wall. My aunts and uncle told him he was “so Pinoy, so malambing (affectionate).”

They loved how he said, “magandang gabi (good evening)” with an American twang and “may nana (with pus)” instead of “malinamnam (yummy)” to compliment dinner. He made the rookie mistake of drinking water straight from the tap, prompting my parents to talk to him on his second morning about how much Imodium he should take. (“If you take more than one,” my father cautioned him, “you’ll be clawing the walls.”)

Over the next 3 and a half years, we would row down the Mekong Delta in Vietnam; support each other through his prostate cancer; be each other’s emergency contacts; share a joint bank account; live together; play nightly games of Jeopardy; and introduce each other to my favorite band (Air Supply) and his sports teams (the Red Sox, Bruins, Celtics). He has become a kuya (older brother) to my sisters; the youngest Facetimes and texts with him regularly.

In our wedding in August, our shoulders were wrapped in his late father’s tallis. I walked around him 7 times and he stepped on glass. (Mazel tov!) Though much of the wedding included Jewish traditions, the rest of it was our own. The wedding party danced down the aisle to Bon Jovi’s “Livin’ on a Prayer” and I, Belinda Carlisle’s “Heaven Is a Place on Earth.” I wore pink sequins. We decided to skip our first dance to John Legend’s “All of Me” and go straight to Def Leppard’s “Pour Some Sugar on Me.”

Though it’s sweet to say that “we don’t see color” or that our religions don’t matter, the truth is, they do.

Our lives are enriched by our different backgrounds and our home, with its rubber tsinelas (slippers) at the front door and the mezzuzah nailed to its frame, reflect that. Last December, we had a Christmas tree and a menorah lighting up our living room.

However, we also need to acknowledge our backgrounds because the moment we step outside our home, our experiences are profoundly different. As romantic as it is to believe in the postracial fairy tale because we have a black president in the White House, the reality is that race still matters. In the US, white privilege is real. I am part of the almost 40% of Asian women who married interracially but that doesn’t mean that I look or feel less Asian or Filipino because I’m with J . My brownness doesn’t fade because he’s next to me in a photo.

J. and I talk about race almost every day. The conversations come up organically. He holds my hand tightly when I am uncomfortable, like when I visited him at his Jewish summer camp where he was an assistant director. He is the first person I told about someone’s yelling “Chink!” when I got off a bus. He has to intervene when I am badgered into answering why I won’t convert.

At high holiday services and bar and bat mitzvahs, I feel in my bones what Zora Neale Hurston meant when she wrote, “I feel most colored thrown against a sharp white background.” He understands that I am proud to be his wife, but I must clarify (when people ask) that I got my green card through employment, not marriage. We want to raise our future progeny Jewish but some believe that children are only Jewish if their mother is.

In the Philippines, Filipinos congratulated me on ending up with a “kano (American).” “Galing! Puti. (Great! He’s white.) Your babies will be so white,” they said. Other comments included, “Is he nice? Cold? Loving?” When they found out he was Jewish, they would say, “He must be rich.” Sometimes, the question was followed by “What do your parents think?”

Before our katulong (househelp) met him, I told them, “Yes, he’s white but he’s malambing” so they weren’t nervous around him, who was the first white person they knew. While a few would ask why I didn’t marry a Filipino, the comments from friends and acquaintances were positive.

But the compliments mostly focused on his whiteness – his skin, his blue eyes – and the assumptions made about his money and class because of it.

In the Philippines, people with lighter skin get “front desk” jobs and end up on TV. White people, even those with little to no acting experience, have cameos as CEOs, American doctors, and ambassadors on local soap operas. I was often told, “You’re so lucky,” but they also meant that our future children were lucky (and lighter) too.

I understand their fascination with his race and it’s ok to be intrigued: at one time in my life, I would have thought him exotic as well. I was 12 when I saw Lea Salonga kiss Simon Bowman in a Miss Saigon special on TV. After I saw my white American childhood dentist with his Filipino wife, I immediately thought of him as kinder and more open-minded, somehow.

Because of systematic discrimination in Saudi Arabia, I didn’t have any friends who were American, much less white. (Though our parents worked for the same company, American and British citizens attended different schools from other countries’ citizens.) As a romantic middle-schooler in Saudi Arabia, I didn’t daydream about ending up with Fred Savage because, honestly, I couldn’t imagine a place where we’d even be friends. Marrying someone like J. was as farfetched as Oz.

It was difficult initially to explain to J. that I lived in a different part of town for no other reason than my citizenship. Sometimes I have to explain what I see and feel, the subtle cuts and slights that might be invisible to him.

Once in a while – at the airport when I see his passport or in photos when I notice how orange-red I am next to his pink-blue skin – I’ll recognize what I would have seen when I was a child: two very different people, different ends of a Sephora color spectrum, different halves of the globe.

He can’t imagine a world where we we weren’t meant to meet and marry. It’s bewildering for me to think of a life where he is not my husband.

In the semi-darkness when I hear him, breathing quietly next to me, I’m stunned sometimes by how we ended up here and how easily we fit. – Rappler.com

Kristine Sydney is a private high school English teacher in the United States, where she has lived for 20 years. Born in the Philippines and raised in Saudi Arabia, she attended boarding school and college in the US, where she practiced her Filipino by reading Liwayway. She writes about immigration, Air Supply adoration, and her intercultural relationship on her blog kosheradobo.com. Follow her on Twitter @kosheradobo.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.