SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Given how long my mother breastfed me (19 months) or how I was born two weeks after my due date, it’s a wonder I ever left home. My giddiest time at the rare sleepover I attended was sunrise because that meant I could return to my house.

Given how long my mother breastfed me (19 months) or how I was born two weeks after my due date, it’s a wonder I ever left home. My giddiest time at the rare sleepover I attended was sunrise because that meant I could return to my house.

When I left Rahima, Saudi Arabia, at 15 for boarding school in the US, I knew that it would be the last time I would be home for more than several weeks a year.

That night was a painful mix of excitement and misery and I decided, then, that whatever I chose in the future would be contingent upon how much time I could spend home. (Admittedly, long vacations were my primary motivation for becoming a teacher and one of the reasons I was confident about marrying J., who understood that spending my summers with my parents was necessary.)

It has been more than 20 years since I unpacked my bags abroad but I still wail at the airport, as if it is my first time. By the time I reach Customs, I am weeping. Behind the glass, my mother mouths, “Call me when you land.”

She is my best friend, my confidante, and the force who centers me. When J.’s and my home was robbed last spring, the thieves stole my mother’s favorite ring, which she gave me when I asked for it. I could not afford to replace it, even if I knew where to find it. “You owned it for such a long time,” I said.

“Did you feel beautiful when you wore it?” she asked, her voice comforting me over 12 time zones.

“Yes,” I said.

“It’s just a thing. Let’s be thankful that we both felt beautiful while we had it.”

I heard the word “beautiful” often growing up. In fact, it was one of the earliest words that my sisters and I learned to say. Used to describe pancakes, movies, dresses, and her daughters, when she said “beautiful,” she extended the syllables. She grew up in Pangasinan where she held onto a 5-centavo bus fare so tightly that it left an imprint in her palm.

She still finds beauty in the simple, like really good daing (dried fish), garlic fried rice, and patis (fish sauce). She’d lift her leg, resting her knee against the table, and say, “Kain na!” (Let’s eat!) But this former country girl also believed that you should use your fine china and crystal glasses daily “because every day is a special occasion.”

She kept my sisters’ plastic Disney pendants next to her jewelry. She made fried chicken for breakfast. Her exuberance was so gorgeous that when friends came over, they would ask if it was someone’s birthday.

She taught me how to read when I was 2 1/2 and, instead of “good job,” after learning plurals, I got “beautiful.”

At 4, I asked her to wrap my feet in tape and rip a tee-shirt’s collar so I could sweat to “Maniac” like Jennifer Beals in Flashdance. Last spring, I found my dream bridal gown – pink sequins and tulle sleeves – but it felt snug when I tried it on 6 weeks before my wedding. “We’ll just rip out the back [if it’s tight]. It’s not a problem.” That afternoon, she came home with my 20-foot veil and a bag of Singapore-style chili crab from Quiapo.

I am sure that the reason I avoided body shame issues as a teenager was that I had internalized a childhood of her telling me that I was wonderful, just as I was. With her, there were no milestones I had to hit or bars to raise. She never asked me when I was planning to marry or when she was going to get grandchildren. “If it’s meant for you,” she would say, “it’s yours.”

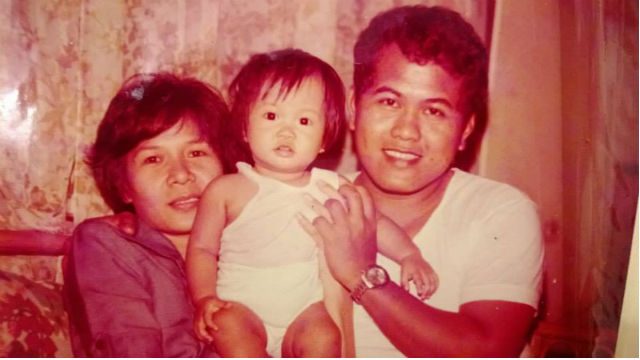

I would often tell her, lying in her lap. “Have you always been this beautiful?” As a teenager, she was a beauty queen. In college, she was the ROTC muse. (My dad talks about how nervous he was the first time he saw her: “I told her I could pierce a can of evaporated milk with my teeth.”)

“Thank you,” she would say. “Anak talaga kita.” (You might be my daughter.)

“No, really,” I would counter, “you must have been the most beautiful woman ever. You’ve won all those contests .”

“I wasn’t,” she would say, “but I was kind.”

One afternoon, she noticed that my skin was pink. I was about 7 or 8 years old. She touched my arms and looked at my neck, which was covered with scratches.

“I think you’re rubbing too hard,” my mother said. “Or maybe your bath water is too hot?” She put baby powder on my arms and some Bacitracin on my neck.

“Why am I not fair like you?” I asked her. She was French-braiding my hair.

“What do you mean?” She stopped.

“I mean, why am I so dark?” I said. Unlike my mother who has porcelain for skin, I had taken after my father’s side of the family, the side of dark skin. In a black-and-white family photo, my sisters sat next to her, their skin luminous. I stood out, the dark daughter. Although I used sun block religiously, I would still come out of the pool, my tan lines more pronounced. I had recently found a picture of a cross section of skin.

It showed the skin as 3 main layers, not too different from sheets of Play-Doh stacked on top of each other. I knew that one’s tan faded over time, but I figured that I could speed up the process. If I removed my dark epidermis, I thought, the lighter dermis would push to the top. For the last few mornings, I had taken a dry, abrasive face towel and exfoliated my skin until it was raw. It hurt to get in the shower.

I cannot recall what she told me that afternoon. I’m sure she must have told me I was perfect the way I was. She might have invoked God. She might have said something silly like my father needed at least one daughter who looked like him. What I know is it worked. After my skin healed, I went back to the pool.

My mother, who does not swim, often went to the South Pool with my dad, my sisters, and me. She sat in a beach chair, as I played Marco Polo and dove into the 12-foot side, pretending I was a brown Esther Williams kicking my feet in the air. “Mama,” I would yell before I disappeared into the water, “watch me!”

Knowing she was there, I glowed. – Rappler.com

Read previous stories from this author

• Taking off my shoes: ‘How clean is the dirt in America?’

• Pacquiao ‘insult’ a cultural misunderstanding

• How asking ‘Are you Filipino?’ can save a life

• Our interracial and interfaith marriage: Yes, color matters

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.