SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

%202011-1.jpg)

MANILA, Philippines – I was recently asked to give a lecture on sex-selection and child policy throughout the region. Were Asians in general choosing sons over daughters to the point of sex-selective abortion? How did sex ratios in South Asia compare with those in East Asia and Southeast Asia?

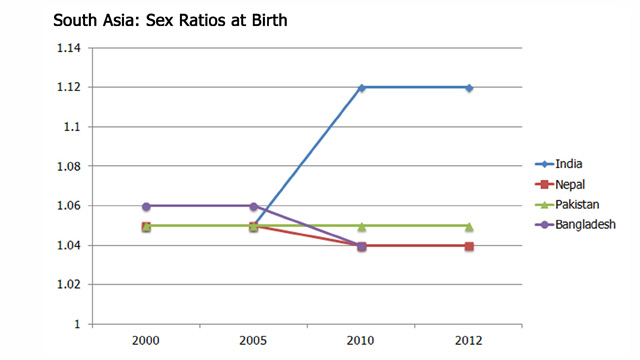

Girls tend to survive boys better in early childhood in general, making the ideal sex ratio around 105-106 boys: 100 girls (read as 1.05 or 1.06). Anything significantly above or below, therefore, begins to be demographically problematic.

Islamic countries

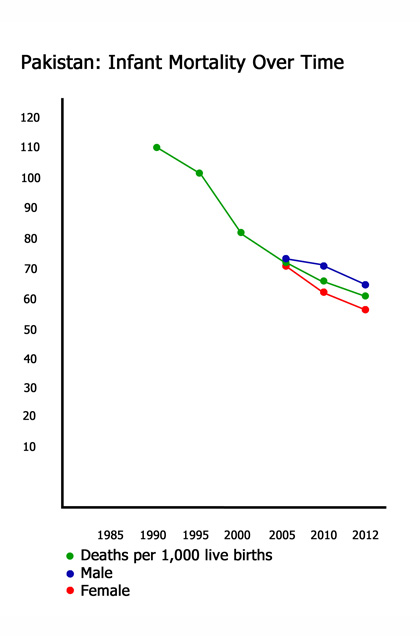

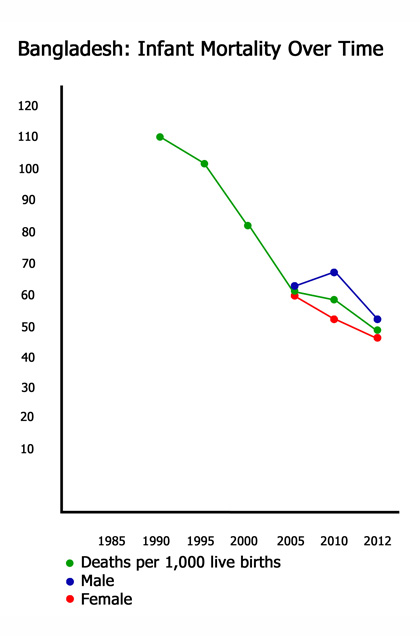

If you had to hazard a guess as to which bloc of countries would be most guilty of female infanticide, what would you say? As a non-expert in Islam and a long-time advocate of women’s rights, my first impression had been that Pakistan and Bangladesh in South Asia (and Indonesia in Southeast Asia) would have some of the most skewed regional ratios.

But apparently impressions at first blush can be dead wrong. It turns out that they have some pretty impressive ratios indeed, much of which has to do with Islam. Despite the complex relationship between the Koran and the hadiths, as well as the sectarian differences between Sunni and Shi’a, there does appear to be collective agreement on the prohibition of abortion itself, regardless of fetal gender.

In Islam, abortion is seen as a crime unless performed to save a woman’s life or to provide “necessary treatment.” With a woman’s consent, it can lead to punishment of up to 3 years; without it, to as much as 7 years.

South Asia

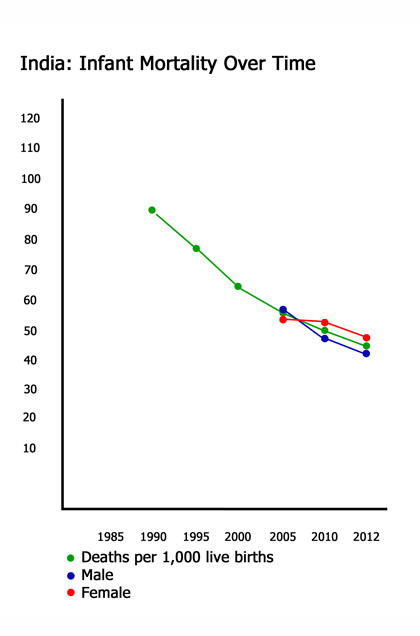

In South Asia, one of the toughest places in which to be an unborn baby girl is apparently India.

With 112 men: 100 women, we can understand Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen’s deepening concern about the millions of missing women in the region. Some states like Punjab have sex ratios as high as 1.20. Every day, women are trafficked into brothels in Mumbai and elsewhere.

Consider India’s cultural history: although early Vedic animism and Buddhism were respectful of women to some degree, and there have been strong female figures (Kali and Durga, for instance) in Hinduism itself, later Vedantic monotheism was more stringently patriarchal.

In the Mahabharata, Draupadi was famously married off to five Pandava men in one family, whom she essentially had to “serve,” demonstrating how women are treated in this ancient epic. Islam, brought to North India by the Persians, was also deeply patriarchal.

East Asia

In East Asia, the most worrisome country appears to be China, known for the one-child policy instituted by the Communist government in 1979. With a population of 1.3 billion, a sex ratio change from 1.08 to 1.09 represents as much as 13 million girls not being born.

In January 2010, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) observed that, in 10 years, one in 5 young men would be unable to find a bride because of the dearth of young women in the country – unprecedented in a country at peace. Staggeringly, this represents 260 million men.

A seminal study by Edlund et al (“Sex Ratios and Crime: Evidence from China’s One Child Policy,” 2007) demonstrated that most violent and property crime tends to be committed by young men – for whom, conversely, marriage can be very stabilizing.

![[Graph] Crime rate rises with increased sex ratios](http://go.rappler.com/images/RESIZED_Residual%20crime%20rate.jpg)

The cluster graph above shows the crime rate rising with increased sex ratios. Poor men tend to be greatly affected by sex ratio inequities, increasing a tendency towards crime and violence – hence the line moving upwards.

![[Graph] Corruption is less impacted by sex ratios](http://go.rappler.com/images/RESIZED_Residual%20corruption%20rate.jpg)

Corruption, however, tends to be less impacted by sex ratios. The rich and corrupt can usually afford to get wives either way – hence the flat line.

Although officially atheistic, Buddhist undercurrents (focusing on the enlightenment and salvation of the Self) in China are often overpowered by Confucian ideals, which tend to revolve around a dominant patriarchal order and place familial and social harmony above all else.

Southeast Asia

Both Buddhist Thailand and Islamic Indonesia permit some forms of contraception, while remaining intolerant of abortion, which may explain why their sex ratios remain good. But while Vietnam and the Philippines have a shared Catholic colonial history, they happen to be polar opposites on this issue.

The Philippines has very restrictive abortion laws, while Vietnam (now officially atheistic) has unrestricted abortion on demand. Already, demographers are concerned that it could follow the path of China and that birth ratios could reach as high as 1.25.

As for the Philippines, it is difficult to get data on sex-selective abortion because it remains illegal in this country. But the problem here is less about sex ratios, considering the fairly high status of women prior to Spanish colonial rule and among indigenous traditions.

Indeed, the status of women according to the Gender Empowerment Index (GEI) is especially strong, at least among the elite and middle classes.

However, we have other pressing concerns. Today, 221 Filipino mothers die with every 100,000 live births. The national conflict over the reproductive health (RH) bill weighs most heavily on the poor: the birth rate of the poorest 20% is roughly double that of the national average.

We now have one of the highest birth rates in Asia, the worst poverty situation in the Asean 4 region, and are the 12th most populous country in the world.

Each country, it need not be said, is unique. But clearly, religious culture has had a powerful impact on the sex ratios of each country in the region. Already, the United Nations has estimated the systematic killing of females – or femicide – at over 100 million girls.

Unless we act soon, the implications for crime, violence, and the perpetuation of the species itself could be potentially harrowing for us all. And Sen’s plaintive query – where have all our young girls gone? – will remain one of the most tragic, if unanswered, questions of this entire generation. – Rappler.com

Lila Ramos Shahani is Assistant Secretary and Head of Communications of the Human Development and Poverty Reduction Cabinet Cluster (which covers 20 government agencies dealing with poverty and development). This piece was based on a lecture she delivered at the Center for Development Management at the Asian Institute of Management, where she is a member of the adjunct faculty. She is half-Filipino and half-Indian.

You might like:

Elsewhere in Rappler:

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.