SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

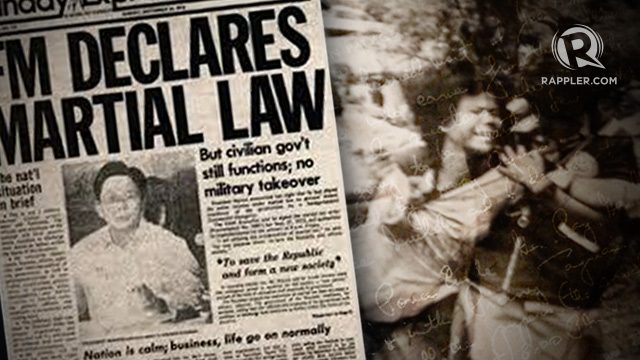

The Philippines commemorated yet another anniversary of the People Power Revolution which ousted President Ferdinand Marcos from power on February 25, 1986. It appears, however, that 29 years later, any collective memory the Filipino people have of the abuses carried out by the Marcos regime during martial law is in danger of being extinguished.

The Marcos family has long been back in power, and even highly educated Filipinos deny that abuses were committed and wax nostalgic about how peaceful and orderly the country was during martial law. Such pro-Marcos sentiment will only become more palpable as the 2016 elections draw closer.

My uncle Enrique Voltaire Garcia II spoke out against the abuses of the Marcos administration. He was a prominent student leader at the University of the Philippines and a promising lawyer elected as a delegate to the 1971 Constitutional Convention.

When martial law was declared, he was arrested along with opposition leaders, journalists and activists, including Senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. Voltaire was eventually placed under house arrest. He was prohibited from traveling to the US to undergo required treatment for his leukemia. A few months after his house arrest was lifted, Voltaire succumbed to leukemia at the all-too-young age of 30. I had not yet been born.

Martial law abuses

There is a need for a comprehensive record of martial law abuses. The creation of an institution tasked with recording victims’ accounts of the mistreatment they underwent during martial law was not a priority. Instead, the immediate concern was the recovery of the Marcoses’ ill-gotten wealth.

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR), a constitutional body with a broad mandate but limited powers, has only recently begun compiling interviews of martial law victims and materials from that period for preservation and commemoration. It plans to display these documents in a future Martial Law Museum. Task Force Detainees of the Philippines (TFDP) maintains its own Museum of Courage and Resistance, containing 6,000 thoroughly documented cases of human rights violations during the martial law era.

Amnesty International documented incidents of torture to detainees during the initial 4 years of martial law. While these initiatives from both public and private sectors are to be lauded, it is nevertheless lamentable that these efforts were not undertaken as soon as practicable after the ouster of the Marcos regime, with government funding and support.

In contrast to the Philippines, commissions of inquiry or truth and reconciliation commissions have been established in countries recovering from civil war, such as Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Liberia; or those emerging from decades of oppression under apartheid, like in the case of South Africa.

The UN Security Council and UN Human Rights Council created numerous commissions of inquiry at the international level to document and investigate rights violations of international humanitarian law in various states. These bodies have, to varying degrees, enabled the countries concerned to move on from difficult periods in their history and rebuild themselves, or in the countries where conflict persists, to at least establish an accurate record of past and ongoing abuses, and to provide leads to investigators for eventual prosecutions.

Legal initiatives

In 1994, a US court in the case of Hilao v. Estate of Marcos (Hilao) found the estate of President Marcos liable for torture, enforced disappearances and summary executions during the martial law era, resulting in a landmark jury award totalling around $2 billion or P90 billion. This decision was affirmed on appeal.

Republic Act No. 10368, otherwise known as the “Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013,” was enacted in February 2013, providing the mechanism through which more than P10 billion accrued interest will be distributed to victims of human rights violations committed during martial law.

This law lays down a conclusive presumption that the nearly 10,000 class action Hilao plaintiffs and those recognized by the Bantayog ng mga Bayani Foundation are victims. A Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board is established which can grant individuals the status of victims eligible for compensation. The law also mandates the creation, under the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission, of a compendium of the suffering endured by the victims. This commission is to also coordinate with the Department of Education and the Commission on Higher Education to ensure that school curricula incorporate lessons on martial law abuses and their victims.

Record of abuses

One hopes that the various initiatives detailed above succeed in compiling an accurate and publicly accessible historical record despite the passage of time and the fading of memories. In addition to documenting victims’ suffering, this record should highlight the efforts of the brave men and women such as Voltaire who had spoken out against tyranny and oppression in spite of the grave risks their activism posed.

This record should be integrated into school curricula in a thoughtful manner, ensuring that future generations take the lessons learned from such record to heart. It is only with such a record and awareness of its contents that misinformation regarding the purportedly idyllic conditions prevalent during the Marcos regime can be effectively dispelled.

The Philippines must learn from the mistakes of the past, and not simply attempt to forget and repress them like bad memories. Only by fully acknowledging this dark chapter in our history can we hope to avoid subjecting ourselves anew to such oppression in the name of peace and order, and to become a truly great, prosperous, and democratic nation. – Rappler.com

Photo courtesy of Dr Ferdinand Llanes, from the exhibit of UP Likas and Official Gazette

Raymond Sandoval is a trial lawyer in the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, The Netherlands. He was previously a legal officer for three and a half years in Trial Chambers of both the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague, and the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in Arusha.

The views expressed in this article are of the author alone in his personal capacity, and do not in any way represent the views of the International Criminal Court or of the Office of the Prosecutor.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.