SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Gabriel Casuga had always wanted to become a doctor. But not just any doctor.

After watching on national television the life story of former Senator Juan Flavier – who himself was a doctor serving in the barrios (rural villages) prior to becoming Health Secretary – Casuga resolved to serve the barrios as well.

A fresh graduate from medical school at that time, he was deployed to the town of San Jorge in Samar. But his supposedly two-year service in the town was cut short after a perceived threat from the municipal mayor.

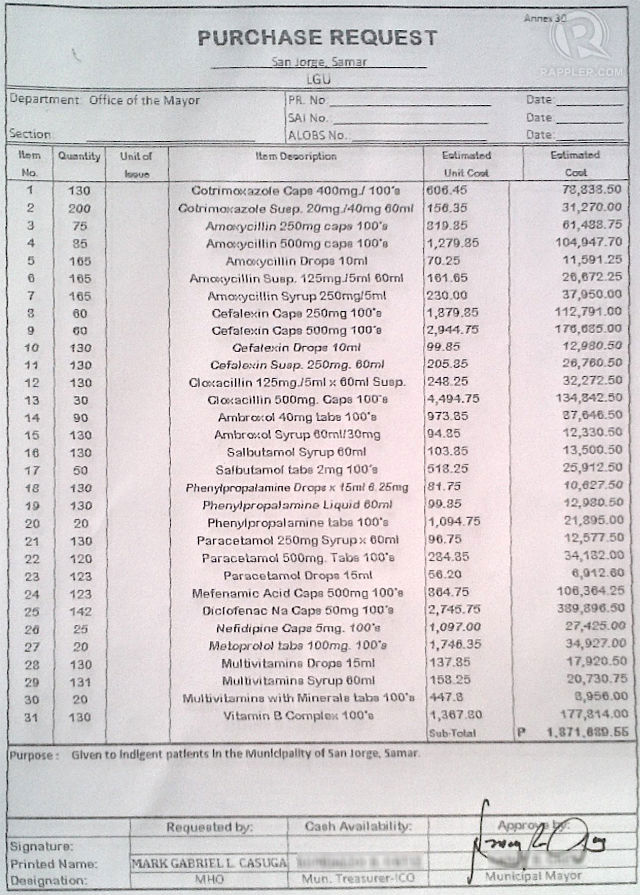

Dr Casuga refused to sign a purchase request of P2-million worth of medicines in January 2012 which, he was told, had already been distributed to town residents the year before.

“Questionable kasi ang purchase order, dadaan pa yan sa committee. Tapos previously distributed na siya. Dapat previous officer-in-charge ang mag-sign,” he said. (It was questionable, because the purchase order should go through the committee. And then the medicines were already distributed. It should be signed by the previous officer-in-charge.)

Casuga was referring to the Bids and Awards Committee (BAC), which supposedly supervises the procurement of goods and items for the town.

Post-devolution

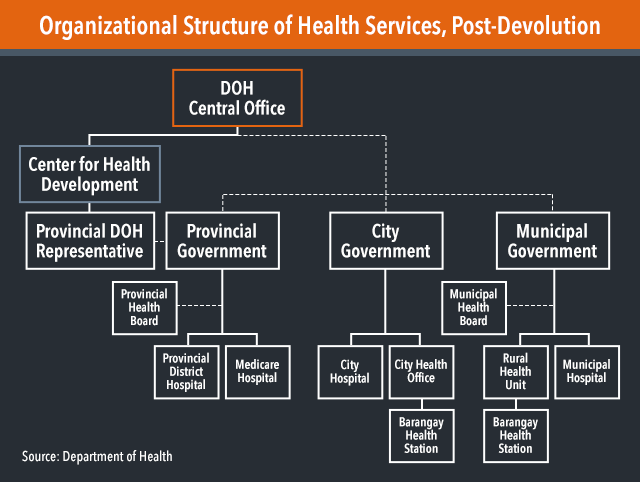

Filipinos have benefited from the devolved functions of local government units (LGUs). The devolution expedited the delivery of more nuanced services based on hyperlocal needs.

The independent procurement of medicines per local government, however, has raised issues of wasted money and the inefficient selection of purchased drugs. (READ: Are LGUs hampering access to medicine?)

In the Department of Health (DOH) set-up prior to devolution, the health professionals had the upper hand in managing health resources instead of the local executives. Today, it’s the other way around.

Casuga shared how the purchase request for over P100,000 worth of Cotrimoxazole, for example, that the mayor asked him to sign was not a priority based on the health needs of San Jorge residents.

The money, he said, could have been spent for a simple lying-in center in the rural health unit (RHU).

Overpriced medicines

Another doctor – deployed in a 4th-class municipality in the Visayas – said the irregularities in the purchase of drugs by LGUs have been a source of frustration for him.

Sharing his experience with Rappler, the 26-year-old doctor said he was shocked by the steep prices of purchased medicines and medical supply. He had requested for the drugs for his RHU some time in December 2012.

“Even test tube brushes, which cost around P10-P20 perhaps, cost P350! Gloves which cost P120-P150 pesos are priced P550 in that receipt. Amoxicillin syrup which costs P15-P20 is priced P115,” he said in an interview. The receipt was dated Jan 13, 2013.

The system is simple, based on what the doctor deduced from his experience: the supplier and mayor “agree on a certain jacked-up price” where both get to have their share from the extra amount added on top of the medicine’s real price.

“If I did the purchase myself and not thru the Bids and Awards Committee, the amount would just have been around P60,000-P80,000,” he said, adding that it could have saved the municipality some P320,000.

“And worse, I cannot object to it. I fear for my job and life, so I didn’t want to contradict higher-ups on matters like this,” said the doctor, who requested anonymity.

Medicines as political tools

The same doctor sees around 20 patients a day. As in Casuga’s case, medicines are dispensed to residents at the Office of the Mayor and not at the rural health unit (RHU).

“All patients who need medicines as per my prescription have to go to his (mayor’s) office to get the medicines themselves… Even this much jacked-up medicines are used as political tools,” he said.

Casuga said this set-up affects the “continuity of care” delivered to the town residents.

“Sana makita ko rin na tama yung makukuhang gamot… [Yung nagdi-dispense] mga waiters ni mayor na wala namang health background,” he said in an interview. (I hope I can also see they are getting the right medicines. Those who dispense the drugs are waiters of the mayor with no health background.)

Casuga narrated an instance when a patient came back to him with the wrong medicine and said “yun yung binigay sa taas (that’s what they gave upstairs [in the mayor’s office.])”

A mother with her 5-year-old suffering from pneumonia was also hesitant to go to the mayor’s office to ask for the prescribed medicine, as she was not a voter.

Threat to life

Casuga is not the only doctor who was transferred to another town due to a perceived threat to life.

A doctor who was previously deployed in another town in the Visayas also refused to sign bidding documents that the mayor asked her to sign. The bidding was dated Jan 4, 2012, a day when she was on leave for her sister’s birthday.

“Actually, everybody sa internal, they advised me, ‘Pirmahan mo na lang yan. Okay lang yan. Papel lang yan.’ Pero hindi eh,” she said. (Actually, everybody in the office advised me to sign the papers. They told me, “It’s okay. It’s just paper.” But no.)

“It will haunt me for the rest of my life, the rest of my career… Bakit ko isasakripisyo yung buong buhay ko (Why will I sacrifice my life) just for the comfort of this one person?” she asked.

The doctor, who is now a Municipal Health Officer (MHO) in a different town, said she was pulled out of the town due to “poor LGU support” and “threat to life.”

Exclusive use of ambulance

In an interview, the female doctor also shared how the town mayor asked her for the exclusive use of the town ambulance.

“Sabi niya, ‘yung ambulance, you should only use that for my mga kapartido, kasi kung hindi ko kapartido huwag mo pagagamitin yang ambulance.’ Sabi ko, ‘paano po kung life and death situation na kailangan talaga ng ambulance?’” she narrated her conversation with the mayor.

(He told me, “only my partymates should be able to use the ambulance.” I said, “what if it’s a life and death situation and the ambulance is really needed?”)

“Sinabihan niya ako na hayaang mamatay yung mga patiente. Sabi niya, ‘Bakit ko sila tutulungan kung pagdating ng eleksyon ilalaglag nila ko?’ Sabi ko, ‘hindi ko po yun kayang gawin eh.'”

(He told me to just let the patients die. He said, “Why should I help them if they will leave me hanging during elections?” I said, “I couldn’t do that.”)

Address corruption

Casuga, who is now in residency training for surgery, worked as an MHO in San Jorge under the “Doctors to the Barrios” (DTTB) program, which deploys fresh graduates of medical schools to poor and remote municipalities.

DTTB is a program of the DOH launched by Flavier, who has inspired many with his life story.

But many of the doctors under DTTB are forced to compromise their principles as they finish their two-year service in the towns they are assigned to.

“New graduates like me really find it difficult to do our work efficiently and more easily. Often we need to bend our principles just to get some jobs done,” said one doctor.

“Corruption perhaps is a bigger and more frustrating cause of why medicines are not accessible,” he added. – Rappler.com

Pills and stethoscope image from Shutterstock

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.